|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Carter Phillips should have had it made. The Sidley Austin chairman has argued a breathtaking 83 times before the United States Supreme Court – more than any private-practice lawyer in America. With that kind of advocacy experience, surely he has what it takes to win more arguments at home than the average husband. Except his wife, herself a lawyer, has attended 81 of his arguments. So even at his kitchen table Carter Phillips faces an expert in how to tell him he’s wrong.

|

|

|

|

|

Despite the huge impact that some Supreme Court decisions can have in our daily lives, the Court goes about its business in relative obscurity. I’m pretty confident that if I stood at the corner of Broad and Walnut Streets -- the center of downtown Philadelphia -- at high noon on a Saturday, holding a picture of Justice Anthony Kennedy, and asked 50 passersby to identify the man, I’d need only the digits on one hand to keep the tally. Yet, of course, Kennedy, as the often-swing vote on the Supreme Court, is one of the most influential men in America.

But lately things have been a little different. The Court, in shocking fashion, lost its most colorful and best-known Justice. On top of that, because the process for finding his replacement is going to play an important part in the Presidential race, it will received out-sized media attention. There have also been hugely-publicized and wide-impacting decisions recently, addressing the Affordable Care Act and marriage equality. On account of this confluence, for more Americans the Supreme Court has stepped out of the shadows.

With all this, there seemed no better time for a Supreme Court issue of Coverage Opinions. So I went straight to the top. And to my delight, Carter Phillips was kind enough to let me ask him some questions about standing behind the most imposing of all courtroom podiums. But his consent came with a warning. Compared to others who have been interviewed in Coverage Opinions, he was concerned that any conversation with him would be disappointing. Welcome to the humility of Carter Phillips. I told him I’d take my chances.

[Speaking of prior Coverage Opinions interviews, I interviewed larger-than-life and billionaire Texas plaintiff’s attorney Joe Jamail for the April 1, 2014 issue of CO. The late-Jamail was long called, and deservingly-so, The King of Torts. That makes Carter Phillips, with his record number of appearances before the Supreme Court, The King of Re-Torts. [For sure, poetic license on my part here. A retort is not exactly how to describe a response to a question from a SCOTUS Justice. But you get it. I just couldn’t resist the line.]

The 63 year old Canton, Ohio native could not have been nicer or more forthcoming during our call. Despite battling a bad cold he set aside a generous block of time and was in no rush to rid himself of me. And he kindly answered some follow-up questions via e-mail.

Frequent Trier Club

That Carter Phillips is a platinum member of the Supreme Court’s frequent trier club should come as a surprise to no one. He started his career there -- serving as a clerk to Chief Justice Warren Burger from 1978-79. He clerked the prior year for Judge Robert Sprecher of the Seventh Circuit. Phillips’s clerkships followed his graduation from Northwestern Law School, where he met his wife on their first day.

While Phillips’s notoriety comes from his seven-dozen SCOTUS appearances, Washington’s One First Street, N.E. isn’t the only courthouse where he plies his trade. Phillips has argued over 100 cases in the United States Courts of Appeals, including at least one in every Circuit. A Westlaw search of cases for Phillips brought back close to 500 hits. [The pesky New York City law firm of Carter, Carter & Phillips and Virginia lawyer Bradford Carter Phillips made it a tad harder to calculate.]

It’s one thing to step up to the plate a lot. But wins is the number that matters most. Just ask the Cubs. In “Who Wins in the Supreme Court? An Examination of Attorney and Law Firm Influence,” Marquette Law Review, Volume 100 (forthcoming), Adam Feldman, lawyer turned Ph.D. candidate at USC, undertook a mind-numbing, and incredibly impressive, statistical analysis of this question. One of Feldman’s metrics – “mean overlap value” -- measures how much language from a lawyer’s brief ends up in an opinion. Phillips is second (only behind John Roberts, from the Chief Justice’s days on the other side of the Supreme Court bench). As Feldman put it: “[N]ot only is Phillips a seasoned Supreme Court litigator, but he is also one of the most successful Supreme Court brief-writers.”

While Phillips may be at the top of the list of Supreme Court repeat performers, others also ask if they may please the court on a regular basis. This is the result of a shift in high court practice. Phillips explained to me that, prior to the mid-1980s to early 1990s, it was common for a lawyer whose case was accepted by the Supreme Court to continue to handle it. But since that time, he told me, cases at the Court have been dominated by lawyers – sometimes two or three per case – who have argued before the Court numerous times. While it’s not unheard of for a first-timer to show up at the Court, Phillips saw that most likely to happen in a criminal case, where substantial resources may not be available.

I asked Phillips if he thinks that SCOTUS Justices are harder on guys like himself – those who make frequent appearances before the Court? Is more expected of them? In Phillips’s view, they can be. But it’s not because the Justices are trying to play games. It’s because they expect that they can get an answer to any question that they have. As Phillips explained it, the Justices are harder on lawyers who actually answer their questions -- because they’ll continue to ask questions. On the other hand, the Justices may back off from some lawyers because they are not going to get the right answer -- so they just stop. Phillips also explained that, in some cases, the Justices are more interested in how they frame the question -- in an effort to convincing someone on the Court how to think about the issue – than in his answer.

How The Supreme Court Approaches Cases

I was very curious about how Phillips goes about his preparation for oral argument. Having never done anything of the sort [25 years without stepping into a courtroom for that matter] I had it in my head that it could work like this. You of course need to be an expert on the key cases governing the issue. Then, you need to be able to discuss the cases that the key cases cited. After that, you drill down to the cases that those cases cited. And at this rate, before you know it, you have worked your way back to Marbury v. Madison – or, for the super-prepared, Blackstone.

But it doesn’t work that way Phillips explained. My misconception, about preparation for a Supreme Court oral argument, was on account of my lack of appreciation for how the Supreme Court approaches and decides cases. [That I lack such appreciation came as no surprise to me. While I follow the Supreme Court’s comings and goings through The Wall Street Journal’s extensive coverage, the last Supreme Court case that I read was a summary of one in a BarBri book. The Supreme Court does not address insurance coverage cases -- which are simply breach of contract cases under state law. And I’m just a one-trick pony.]

To hear Carter Phillips explain his views on the way that the Supreme Court approaches cases was extraordinary – for both its enlightenment and privilege. It is not my practice to use long quotes in CO interviews. But something this insightful needs to be set out verbatim. If I tried to summarize it I would only mess it up. Phillips’s explanation, of the way that the Supreme Court approaches cases, in response to my question about his preparation for oral argument, went like this:

There is a very different dynamic that operates if you are arguing in front of the Supreme Court than if you are arguing before the Court of Appeals. The reality is that the Supreme Court rarely thinks of itself as being bound in by any particular precedent in the sense [that] they don’t usually grant cases where the precedent points decidedly in a particular direction. They usually grant cases because they have not decided the question before and they don’t tend to think of the ultimate decision as being driven by precedent nearly as much as what I would think of as first principles. What does the text of the statute say? What does the text of the Constitution say? How is it understood? How should it be understood? What canons of construction are available in a particular case? Case law itself tends to drop down in the pecking order of considerations.

Lower courts obviously are much more attuned to precedent. Obviously they are very concerned about what the Supreme Court says and trying to read tea leaves there. Clearly they are bound by their own prior decisions but they also tend to be more respectful of other tier courts – the Courts of Appeals. Whereas the Supreme Court really doesn’t typically care that much about what lower courts think about an issue. Indeed they delight I think in finding issues where all twelve Circuits have lined up on one side and announcing to the world that all of those courts are wrong and the right answer is something that nobody ever thought of.

In that sense you don’t really have to read a thousand cases in order to be prepared for a Supreme Court argument. To be prepared for a Supreme Court argument you have deal with the core of what’s the right answer for this particular case. What interests are likely to influence individual Justices in one direction or another? If you have Federalism principles and you can promote the States’ interests that’s a good one to have. If you have the federal government on your side that’s a good one to have. Those kinds of things make much more of a difference than whether you can cite to a particular case or quote the court from a particular opinion.

On the subject of precedent, Phillips told me that the best piece of advice he ever got as a Supreme Court advocate came from his former boss – Chief Justice Burger. The Chief told him that “when you read a Supreme Court opinion you shouldn’t assume that it means what it says and says what it means.” In other words, Phillips explained that a precedent may seem to lean in one particular direction. But the Court will write an opinion stating that, while its prior decision could be read one way, it concludes that the better reading is another way. So the court walks away from the language in the earlier opinion. Here, Phillips came back to his comments about precedent playing much less of a role in Supreme Court cases than “first principles.”

The Handicapper

It came as no surprise when Phillips told me, in response to my question, that he has solid handicapping skills when it comes to his cases. He said that he is able to confidently tell clients whether the Court will take their case and whether they will win. Then, after oral argument, it is even easier.

Phillips explained that it is the nature of the Court, and its arguments, that give rise to his predictive skills. “There are no devil’s advocates on the Court,” Phillips said. “You only have 30 minutes. You’re going to get 50 to 60 questions. The Justices are actually trying to make points with other Justices more than anything else.” In this context, the Justices are “wearing their views on their sleeve,” Phillips said. They’re “asking a pointed question because [they] want to convey a message to someone else.” When all of this is said and done, Phillips said, “you can count heads and usually it’s not that hard to come up with a prediction as to how the court will come out.”

Memorable Cases

I of course asked Phillips to list a few of his most memorable cases. He pointed to Federal Communications Commission v. Fox Television Stations, 132 S. Ct. 2307 (2012), where he represented Fox, in a dispute with the FCC, over whether certain brief aspects of Fox broadcasts were “actionably indecent.” The hullabaloo came about because of certain uses of the word f*** during Fox’s broadcasts of the Billboard Music Awards. In 2002, Cher used the word during an acceptance speech. A year later, Nicole Ritchie used it while presenting an award. ABC was also a party in the case. The network was on the FCC hot seat on account of a 2003 episode of NYPD Blue that showed the nude buttock of an adult female character for approximately seven seconds and, for a moment, the side of her breast. The FCC concluded that both networks’ broadcasts were indecent.

It sounds like a First Amendment case. But the issue was Due Process (but not without a First Amendment nod). The FCC’s rules, that “fleeting expletives” and momentary nudity are actionably indecent, were put into place after the broadcasts aired. At the time of the broadcasts, a key consideration was whether the material dwelled on or repeated at length the offending description or depiction.

The high court found for Phillips’s client Fox, as well as ABC: “[T]he Commission policy in place at the time of the broadcasts gave no notice to Fox or ABC that a fleeting expletive or a brief shot of nudity could be actionably indecent; yet Fox and ABC were found to be in violation. The Commission’s lack of notice to Fox and ABC that its interpretation had changed so the fleeting moments of indecency contained in their broadcasts were a violation of [18 U.S.C.] § 1464 as interpreted and enforced by the agency ‘fail[ed] to provide a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice of what is prohibited.’ This would be true with respect to a regulatory change this abrupt on any subject, but it is surely the case when applied to the regulations in question, regulations that touch upon ‘sensitive areas of basic First Amendment freedoms.’” Id. at 2318 (citations omitted).

As an aside, Phillips shared with me something about Fox Television that you won’t read in the opinion. ABC, in the dock over a nude buttock in NYPD Blue, was represented by Seth Waxman of Wilmer Hale (and the former Solicitor General). Waxman pointed out to the Justices during his argument that in the friezes above the Court were pictures of male nude buttocks. Justice Scalia, sitting directly across from Phillips, asked “Where?” Phillips pointed to one just about Scalia’s head and said “there.” Then Phillips pointed to another one. And one more after that. Scalia replied: “I never noticed that.”

Phillips told me that his proudest achievement is McNally v. United States, 107 S. Ct. 2875 (1987) – the second case he argued at Sidley. He was successful in having mail fraud convictions of certain individuals overturned. Phillips’s clients had a scheme whereby an insurance agency for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, to continue in that role, agreed to pay certain commissions to other insurance agencies, including one established by his clients for the sole purpose of sharing in the commissions.

The Sixth Circuit had upheld the convictions on the basis that the mail fraud statute includes “schemes to defraud citizens of their intangible rights to honest and impartial government.” This had been seen as an appropriate interpretation of the mail fraud statute by Circuits across the board. But the Supreme Court reversed, holding that Congress’s intent in passing the mail fraud statute was to prevent the use of the mails in furtherance of schemes for obtaining money or property by false promises or misrepresentations.

Phillips told me that this decision resulted in thousands of convictions being overturned. It was particularly satisfying, he explained, because while the Court agreed to hear the case on narrow grounds – whether the intangible rights theory could be applied to a non-governmental official (a political party official) – it ultimately struck down the intangible rights theory altogether.

A year later, Congress responded to McNally by adding “honest services fraud” to the mail and wire fraud statutes: “[T]he term scheme or artifice to defraud includes a scheme or artifice to deprive another of the intangible right of honest services.” 18 U.S. Code § 1346. Honest services fraud has gone on to play a huge part in numerous cases involving corruption. And it is not without its own constitutional criticisms and challenges. But the long and winding road of present day honest services fraud got its start with Carter Phillips and his win in McNally.

The Most Influential Amicus Brief In the History Of The Supreme Court

In his award-winning book The Nine – Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, Supreme Court scholar and CNN legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin concluded that Phillips may have authored “the most influential amicus brief in the history of the Court.”

The case at issue is Grutter v. Bollinger, 123 S. Ct. 2325 (2003) and involved the permissibility of racial preferences in admissions at the University of Michigan Law School. As explained by Toobin, race conscious affirmative action had been very important for the military service academies – used to prevent large groups of enlisted minorities from being commanded by all white officers. The University of Michigan wanted to use this success, at West Point, Annapolis and Colorado Springs, in support of its position. But since active duty officers could not make this argument, the University sought out high-profile military retirees to put their names on an amicus brief.

The University brought in Phillips and colleague Virginia Seitz to write the military retirees’ brief. As Toobin put it, “The implicit question at the heart of the retired officers’ brief was, if affirmative action was good enough for the service academies, why wasn’t it good enough for the University of Michigan?”

The military retirees’ amicus brief became a focal point of the oral argument, with several Justices peppering Solicitor General Ted Olson about it. Justice Ginsburg, noting that all of the military academies have race preference programs in admissions, asked Olson if that was a violation of the Constitution. Toobin described the box that Olson had been put in: “If Olson said yes, he admitted that the federal government was violating the law; if he said no, he looked like a hypocrite.”

The law school’s affirmative action program was upheld by a 5-4 vote. The task to write the majority opinion fell to Justice O’Connor. Toobin described it like this:

O’Connor next turned to the subject that dominated the oral argument—the brief from the retired military officers. She quoted Carter Phillips’s brief at length and then, in an extraordinarily rare tribute, simply adopted its words as part of the Court’s opinion: “To fulfill its mission, the military ‘must be selective in admissions for training and education for the officer corps, and it must train and educate a highly qualified, racially diverse officer corps in a racially diverse setting.’” Before submitting his brief, Phillips had worried that the Court might observe (correctly) that there were big differences between a military service academy and a law school, and thus find no relevance of one to the other; but O’Connor did just the opposite. Quoting the brief again, she wrote, “We agree that ‘it requires only a small step from this analysis to conclude that our country’s other most selective institutions must remain both diverse and selective.’”

Toobin concluded that, “considering the oral argument and O’Connor’s opinion, the submission from the retired officers may have been the most influential amicus brief in the history of the Court.”

Phillips very briefly mentioned Grutter to me when I asked him about his most significant cases. But he said nothing at all about Toobin’s assessment of it. Welcome back to the humility of Carter Phillips.

Catching A Lift With Justice Scalia

Needless to say my call with Phillips had to include some discussion of the late-Justice Scalia. I wasn’t looking for anything complicated, such as memories of an argument that he may have with the Justice over an obscure point of law. To the contrary, my objective was to get a favorite entertaining anecdote. Between the amount of interaction that Phillips had with Scalia, and the late-Justice’s penchant for biting wit, I figured Phillips would have many to offer. I was right. He didn’t even know where to begin.

Phillips shared with me a story that is surely at the top of the list. The tale is also recounted in Toobin’s The Nine. On a Sunday in January 1996, Washington was hit with a crippling 21 inch snow storm. While the federal government was shut on Monday, Chief Justice Rehnquist, unwilling to raise a while flag to the elements, ordered that the day’s oral arguments proceed. The Chief sent cars and Marshalls to pick up the Justices at their homes.

Phillips was scheduled to argue that day in Norfolk & Western Railway Company v. Hiles, a case involving an injured railroad worker. He lived in proximity to Justice Scalia in the Virginia suburbs and caught a lift with him to court. Justice Kennedy also shared the car. Obviously, Phillips said, the case was not discussed during the ride. The three arrived at the Supreme Court with 30 minutes to spare. According to Toobin, Scalia quipped: “I even have time to read your brief now, Phillips.” I guess that’s called an ex-carte communication. This was one of the two oral arguments that Phillips’s wife has missed.

A Reinsurance Joke – Really

Phillips has argued seven reinsurance cases in various courts. Since Coverage Opinions is, at its core, an insurance publication, we talked about the subject briefly. And then Phillips laid this on me: “I do have one funny story to tell you about reinsurance cases.” I was certainly all ears.

Phillips recounted for me a story from many years ago when he was getting ready to argue a reinsurance case in the Second Circuit. Just as the panel was about to come onto the bench, his adversary, Walter Dellinger – the renowned authority on the Supreme Court and former Solicitor General -- leaned over to Phillips and asked him if he knew why reinsurance law was invented? Dellinger said: “To make insurance law seem interesting.”

Yeah. Yeah. Real funny. To a passionate insurance lawyer like myself, those are fightin’ words. Dellinger would be wise to watch his back. There’s a 5’4” bespectacled, bow-tie wearing insurance lawyer out there with a grudge.

Thoughts on Judge Merrick Garland

At the time of my call with Phillips, President Obama had not yet announced his nominee to replace Justice Scalia. But speculation was that the decision was close at hand. So while I asked Phillips his thoughts on who might get the nod, in the back of my head I couldn’t avoid the feeling that it would be for naught. It was. A week after my call with Phillips, the President selected Judge Merrick Garland of the D.C. Court of Appeals to fill Scalia’s seat.

I reached out to Phillips for comment after Judge Garland was tapped. It turns out the two go way back. While Phillips was clerking for Chief Justice Burger, Garland was down the hall clerking for Justice William Brennan. I wasn’t the only one seeking Phillips’s comments that day on Judge Garland. Phillips told me, as he told The National Law Journal, that he didn’t think that Garland would “be a replacement for Justice Scalia in that he’d be asking ten to fifteen questions in 30 minutes of argument.” But Phillips also doesn’t see Garland as a “shy and retiring justice.” “I think he would ask questions and they would be good questions and they would advance the understanding of the justices about what the case is about and what’s the right thing to do,” Phillips said. Having argued before Garland in the D.C. Circuit, Phillips called him “about the nicest person to argue in front of that you could ask for. He’s prepared, he’s thoughtful, he’s considerate, he’s respectful.”

But Phillips did not praise Garland for his performance on one particular court – basketball. As clerk colleagues, Phillips and Garland played hoops a few times a week on the top floor of the Supreme Court building – the so-called “highest court in the land.” “Merrick played hard,” Phillips told me, “but his shot needed a bit of work.” Not much has changed in nearly 40 years – Phillips once again thinks that Garland’s best place in the Supreme Court is on the bench. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Issue 4

March 30, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

The other night I was out to dinner with my 9 year old daughter. As we waited for her mac & cheese to arrive I decided to give her a lesson on the Supreme Court. I figured I’d start with the basic operation of the federal judiciary. From there move on to some landmark Supreme Court cases. And by dessert we’d be discussing the Necessary and Proper Clause. But she wanted no part of it – begging me to stop.

So I took a different tack. I’d tell her about a case and then she would use my phone to find emojis to write out the case name. This idea she loved. While it didn’t last long, as dinner arrived, it gave me an idea: The Supreme Court “Emoji Challenge.”

Name the following landmark decisions from the United States Supreme Court: (answers below)

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

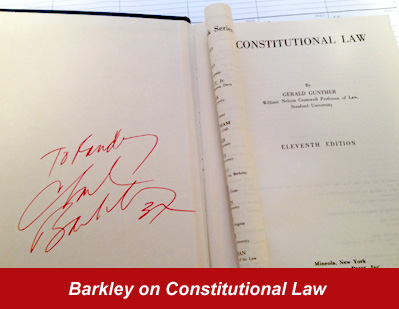

Charles Barkley: Constitutional Law Scholar

|

|

|

|

| |

Since this is the Supreme Court issue of Coverage Opinions it makes sense to share a constitutional law secret that rivals what goes on at the Justices’s conferences.

In the Spring of 1989, the night before my Con Law final, I exited my apartment building in Center City Philadelphia and set off for the library. Within seconds I found myself face-to-face with Charles Barkley. I instinctively said hello and Sir Charles greeted me back. I asked him for an autograph and he was happy to oblige. I sensed that the Round Mound of Rebound was in a rush. So I acted quickly and handed him the first thing I could find for him to sign. This happened to be my Con Law casebook. Charles opened the cover and autographed the inside cover – just as the author would.

Charles Barkley is many things. Add one more to the list: constitutional law scholar. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Join the hundreds who have already signed up!

I am excited to report that Coverage Opinions, National Underwriter and American Lawyer Media are once again partnering on a webinar -- “CGL Policy Road Trip: 66 Advanced Stops Along The Way” - being held on March 30th. This 2-hour webinar will start at the top of the CGL form and work its way through to the end – making 66 stops along the way.

https://www.eiseverywhere.com/ehome/165860

I know that most people reading this already know a lot about the Commercial General Liability policy. Most have been dealing with it for many years and are, in fact, experts. So why would I need to take a CGL policy webinar may be the question that you are asking yourself right now.

Answer: Because the webinar was designed with that very question in the forefront of my mind. In other words, I know that you have years of experience working with the CGL policy. I will therefore discuss advanced topics concerning the policy, focusing on nuances, unique takes on issues, topics that may not be addressed in other CGL seminars and key case law. The webinar will provide maximum opportunity for even the most experienced with the CGL policy to learn new things.

So many seminars and webinars are a complete waste of time and money because the speaker forgets that his or her audience is also very knowledgeable on the subject. So you spend an hour or two listening to someone drone on about things you are already know. And when it’s over you ask yourself, sometimes disgusted – why did I just spend my time and money on that? [Think Rocky V]. I have put this webinar together with a single objective in mind – prevent attendees from having that feeling.

The webinar is geared to both insurer-side coverage attorneys and other coverage professionals as well as those who represent policyholders.

The webinar will offer Adjuster CE and Lawyer CLE credits in several states.

If you found the “50 Item Reservation of Rights Checklist” webinar to be educational, I promise that “CGL Policy Road Trip: 66 Advanced Stops Along The Way” will deliver too.

I hope you’ll check it out:

https://www.eiseverywhere.com/ehome/165860 |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

So, Not So Cute Now:

Woman Uses Emojis And Gets Sued |

|

|

|

|

| |

Randy Spencer will be appearing at Gotham Comedy Club, in New York City, on April 5th at 7 P.M., as part of a New Talent Showcase. Gotham is located on 23rd Street, between 7th and 8th Avenues. Drop him a note for free tickets.

***

As far as I can tell, there are three categories of people when it comes to the use of emojis: (1) those who use them way too much and should have their iPhones confiscated by the FCC (e.g., sending condolences to someone, on the death of their loved one, should not be done via text, using pictures of a crying face and casket); (2) those who never use emojis and, in fact, look down their noses at people who do; and (3) those who understand the purpose of emojis and use them appropriately (e.g., my 9-year old daughter will text me three pictures of an ice-cream cone as her way of saying – let’s go to Baskin-Robbins).

But no matter what type of emoji user you are, the Rhode Island trial court’s decision in Bertha Hopkins, as assignee of Linda Hopkins v. Roger Williams Ins. Co. teaches us that, if you are going to send a text with emojis, be sure that it doesn’t end up in the wrong hands.

Bertha Hopkins hosted a Thanksgiving dinner at her home in 2014. To be in attendance was her daughter-in-law, Linda Hopkins, and several others. Bertha was to make the turkey. In the week leading up to the holiday, numerous group texts went back and forth between Bertha, Linda and other guests, over who would make which side-dishes.

On the day after Thanksgiving, Linda responded to the last group text with a text containing nothing but the following three emojis: . Someone on the text distribution replied, asking what the text meant. Linda did not respond to the group. However, Samantha Roberts, Bertha’s first cousin did. She replied to the group – “the turkey was dry last night.” Linda had meant to remove Bertha from the group text before sending it. But she didn’t. Bertha received both texts and was not amused. She responded to the group, disputing that her turkey was dry and, in fact, claiming that she was a fantastic cook and had never made a dry turkey in her life. But Bertha didn’t stop there. She sued Linda and Samantha for defamation, alleging that both women damaged her reputation as a great cook. See Bertha Hopkins v. Linda Hopkins and Samantha Robbins , No. 15-0236, Superior Court of Rhode Island (2/24/15). . Someone on the text distribution replied, asking what the text meant. Linda did not respond to the group. However, Samantha Roberts, Bertha’s first cousin did. She replied to the group – “the turkey was dry last night.” Linda had meant to remove Bertha from the group text before sending it. But she didn’t. Bertha received both texts and was not amused. She responded to the group, disputing that her turkey was dry and, in fact, claiming that she was a fantastic cook and had never made a dry turkey in her life. But Bertha didn’t stop there. She sued Linda and Samantha for defamation, alleging that both women damaged her reputation as a great cook. See Bertha Hopkins v. Linda Hopkins and Samantha Robbins , No. 15-0236, Superior Court of Rhode Island (2/24/15).

Linda sought coverage for the suit from her homeowner’s insurer -- Roger Williams Ins. Co. Samantha did not own a home and had no homeowner’s insurance.

Linda’s policy provided “personal injury” coverage for, among other things, “[o]ral or written publication, in any manner, of material that slanders or libels a person or organization.”

Roger Williams Ins. Co. disclaimed coverage to Linda. The basis for its disclaimer was that, while Bertha clearly alleged that Linda libeled her, it had been done by way of emojis, which was not in the form of “oral or written publication of material.”

With no defense forthcoming from Roger Williams, Bertha and Linda settled the suit for $20,000. Bertha dismissed Samantha from the action. Linda assigned her rights, under her Roger Williams homeowner’s policy, to Bertha. Bertha executed a covenant not to execute the judgment against Linda.

Bertha sued Roger Williams to collect the $20,000 judgment. The court in Bertha Hopkins, as assignee of Linda Hopkins v. Roger Williams Ins. Co., No. 15-5696, Superior Court of Rhode Island (3/3/16) held that no coverage was owed. As the court saw it, the only possible defamation committed by Linda was in the form of the text message that she sent containing the three emoji symbols. While Samantha had sent a text, using words, stating that “the turkey was dry last night,” Linda did not use written words to defame Bertha. On that basis, the court concluded that the three emoji symbols were not “written material.”

The court chose emojis to state its conclusion:

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Tred Eyerly: Practicing Law In Alaska, Hawaii and Northern Mariana Islands

The last issue of Coverage Opinions featured the inaugural installment of “The Four Questions: Why Is This Coverage Lawyer Different From All Other Coverage Lawyers?” The objective of this new column is to feature a coverage lawyer and ask him or her, well, four questions. I’ll be looking to focus on unique lawyers – be it because of their practice or jurisdiction or something else or some combination of things.

Chuck Browning, of Michigan’s Plunkett Cooney, P.C., kicked things off and was The Four Questions test subject. Thanks to the great job that Chuck did, The Four Questions is continuing.

If the goal of T4Q (my new cool way to refer to The Four Questions column) is to feature a unique lawyer, then it is going to be hard to top Tred Eyerly of Honolulu’s Damon Key Leong Kupchak Hastert. That Tred practices coverage law in Hawaii is unique in itself. But wait. Tred also practiced law for many years in Alaska and the Northern Mariana Islands. In addition to insurance coverage, Ted’s resume includes commercial litigation, personal injury and employment. His career has also included substantial work in the public interest arena.

Tred served as Chair of the Insurance Coverage Section of the Hawaii State Bar Association (2011-2013) as well as co-Editor, ABA, Section of Litigation, Insurance Coverage Litigation Committee’s Website, Case Notes and Articles (2012 – 2015).

Tred Eyerly has handed issues, faced challenges and seen things that most of us can’t even imagine. Of course, perhaps Tred’s greatest career highlight is to have been (successful) co-counsel for the policyholder in C. Brewer and Co., Ltd. v. Marine Indemnity Ins. Co., 347 P.3d 163 (Hawaii 2015) (addressing the interpretation of a Designated Premises Endorsement) -- a case that appeared on my “Top 10 Coverage Cases of 2015” list. [OK, maybe not.]

Tell me about your background and what made you practice law in such far-flung locations?

I was born and raised, and went to undergrad and law school in California. Although admitted in California, I never practiced there. Instead, I spent eleven years in Alaska, ten years in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and have now been in Hawaii for fifteen years.

In law school, one of my housemates graduated the year before me and went to work for Alaska Legal Services Corporation in Bethel, Alaska. He recruited me after I graduated. I started my legal career and lived in Bethel for two years. Bethel is in southwest Alaska, the regional hub for 56 Eskimo and Athabaskan villages, scattered over the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a land mass about the size of Oregon. It was a fascinating experience for a young lawyer. There are no roads to Bethel, so to meet with clients often required traveling by small plane to remote villages. My case load varied, but I primarily worked on land claims for Alaska Native clients.

After two years in Bethel, I relocated to the main office of Alaska Legal Services Corporation in Anchorage. I served for eight years as a statewide litigation attorney working on fascinating issues facing Alaska Natives throughout the state. Cases involved land claims, subsistence, sovereignty, voting rights, employment discrimination, and other issues. I traveled all over the state, from as far south as Ketchikan to Barrow in the north.

Next, I spent the 1990’s in Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. I worked the first four years for Micronesian Legal Services, and then eight years for a small firm. The cases varied tremendously. In a small island community it was difficult to specialize in any particular area. While in private practice, however, I had my first exposure to coverage issues representing the policy holder.

I moved back to Alaska for two years and worked for an insurance defense firm and also continued to do some coverage work.

In 2001, I moved to Hawaii and have now been here fifteen years. My primary focus is on coverage work for both policy holders and insurers.

Obviously Alaska and Hawaii are polar (pun intended) opposites in one obvious way. How does practicing law differ between these two jurisdictions?

The practice in Bethel was more informal. Shirt and tie were not required for court appearances. I was sworn into the Alaska bar wearing a heavy wool shirt and rubber, break-up boots, which was the common attire for the tundra.

Servicing clients all over the state required extensive travel, most it by small plane because there are few roads in Alaska. Being weathered in at a remote village was a common experience because small planes could not fly in a blizzard or foggy conditions. People in the villages were always very hospitable. I was once weathered in over Thanksgiving at a remote coastal village. Our feast included crane instead of turkey.

The practice in Anchorage, the big city, was more formal, as it is in Hawaii. The practice in these locations is similar to mainland jurisdictions, but perhaps more laid-back and civil.

Are there any things about Hawaii coverage law that make it unique from other states? Do you see tourism-related exposures? Claims involving pineapples?

Hawaii case law on insurance coverage issues is in its infancy and continues to evolve. Frequently, the court and litigants must look to other jurisdictions for guidance. This makes the practice exciting because there is always the opportunity to develop new case law where there are no answers to outstanding issues.

Five or six years ago, there were very few Hawaii lawyers who specialized in coverage. More recently, some major construction defect cases, involving numerous parties, demanded the involvement of coverage lawyers so more lawyers have had exposure to coverage issues.

Hawaii is known as an insurer-friendly jurisdiction. This does not always hold true, however, as there are significant exceptions.

A good example is the current state of the law regarding liability coverage for faulty workmanship, construction defect issues. In 2010, the Hawaii Intermediate Court of Appeal issued its decision in Group Builders, Inc. v. Admiral Insurance Co., 123 Haw. 142, 231 P.3d 67 (Haw. Ct. App. 2010), a brief opinion with abbreviated analysis, holding that claims for property damage based upon faulty workmanship did not constitute an “occurrence,” but were contract-based and not covered under a CGL policy. Subsequently, the legislature enacted Act 83, which attempted to undercut Group Builders. The legislation requires consideration of the case law that was in existence at the time the policy was issued in deciding whether property damage due to faulty workmanship arises from an occurrence. Consequently, the dispute between contractor policyholders and carriers now centers on the state of the law regarding “occurrence” at the time a particular policy was issued. While most of the judges for the federal district court for the district of Hawaii have predicted that the Hawaii Supreme Court will ultimately find claims based on faulty workmanship do not arise from an occurrence, the issue has yet to reach the Hawaii Supreme Court.

A Hawaii-flavored coverage case I worked on involved a pineapple plantation on Oahu that inherited a contaminated superfund site. Coverage was denied under policies issued to our client’s predecessor. We filed suit against numerous insurers. The end result was the Hawaii Supreme Court’s decision in Del Monte Fresh Produce (Hawaii), Inc. v. Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co., 117 Haw. 357, 183 P.3d 734 (2007), where the court held that assignments of the policies to our client voided coverage because there was no assignment by operation of law and the insurers had not consented to the assignment of policies.

What are some of your most satisfying public interest successes?

My most interesting public interest work was done in Alaska. A case that stands out was work for a 96 year old Tlingit gentleman, Jimmie A. George, Sr., from the village of Angoon. The case involved a claim under the Alaska Native Allotment Act of 1906 for subsistence land in southeast Alaska that had been used Mr. George and his ancestors. The Bureau of Land Management denied the claim and the Interior Board of Land Appeals affirmed. Mr. George filed suit against the Department of the Interior. The Department of Justice lawyer and I traveled to Angoon to take Mr. George’s deposition. Through a translator, he had fascinating stories about his subsistence life-style in southeast Alaska. After the deposition, we moved for summary judgment. I will never forget the ruling from the bench by District Court Judge Andrew Kleinfeld, now a senior judge on the Ninth Circuit. Judge Kleinfeld was known as a conservative judge and we were unsure of his receptiveness to land claims by Alaska Natives. Nevertheless, he ruled in Mr. George’s favor, noting that the family core making historical use of the land was significant to the judge.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2015

Thank You, Thank you

General Liability Insurance Coverage – Key Issues In Every State

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

The 3rd edition of General Liability Insurance Coverage -- Key Issues In Every State just celebrated its one year anniversary (except any cases involving a dog bite are seven years old).

Sales of the book have been phenomenal! Even after a year sales remain brisk, with some people buying 4, 5, 6 and more copies. Jeff and I can’t thank Coverage Opinions readers enough for the great support that you have given to Key Issues 3.0.

You don’t take on a project like this to get rich. Trust me. You do it for the personal and professional satisfaction that it provides. But that couldn’t happen if people weren’t actually using the book. So with the book sitting on so many of our colleagues’ desks, that goal of satisfaction has been achieved. And for this we sincerely thank you.

See for yourself why so many find it useful to have, at their fingertips, a nearly 800-page book with just one single objective -- Providing the rule of law, clearly and in detail, in every state (and D.C.), on the liability coverage issues that matter most.

www.InsuranceKeyIssues.com

Get the 3rd edition here www.createspace.com/5242805 and use Discount Code NTP238LF for a 50% discount.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

Winners Of The Insurance Coverage Haiku Contest

|

|

|

|

| |

Just as was the case with the first Insurance Coverage Haiku Contest, held in January 2013, Insurance Coverage Haiku Contest 2.0 was very popular. There were tons of entries and it was a huge challenge to pick the two winners. In addition, I am awarding two honorable mentions. All will get a copy of Key Issues 3rd. I know. It’s not like winning the Power Ball – but it’s the best I can do.

And the winners are…

In the Honorable Mention category… [Of course I thought these entries were clever – maybe even the best -- but I would have looked bad if I made them winners.]

No fortuity

Did an occurrence occur?

Must read Maniloff

Barry Miller

Mazanec, Raskin & Ryder, Co., L.P.A.

Lexington, KY

So, is it covered?

You can predict the outcome

Key Issues In Every State

Linda Caswell

Louisiana Companies

Baton Rouge

The real winners are (in no particular order):

The insured did what?

Intentional, on purpose!

Not an occurrence

Jessica E. Pollack

Hawley Troxell

Boise, Idaho

Oh my policy

All I do not understand

But still it will rule

Moris Davidovitz

Davidovitz + Bennett

San Francisco

Congratulations to the winners and thank you to all who entered. |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

Opening Day Upon Us: Update On The Major League Baseball “Foul Ball Litigation”

|

|

|

|

| |

Opening day of baseball season is on the doorstep. So this is the perfect time to check in on the status of Payne, et al. v. Major League Baseball, pending in the Northern District of California. Regular readers know that I have a keen interest in sports litigation involving fans’ interests and rights. Payne falls into this category.

One of the most popular cases in the fan interest category are those involving spectators injured by foul balls at baseball games. They are legion and date back a century. In general, the legal system has almost always denied compensation to spectators injured by foul balls.

In July 2015, suit was filed in a California federal court that took a different tack: An Oakland A’s season ticket holder – not hit by a foul fall -- sued Major League Baseball, and its Commissioner, Rob Manfred, seeking to compel them to expand the area in stadiums that are within the zone of protective netting.

I was thrilled to publish an Op-Ed, in the July 24th issue of The Wall Street Journal, discussing the case and why the suit should fail. I hope you’ll check it out here:

http://www.coverageopinions.info/WallStreetJournalJuly2015.pdf

Here is what’s happening in Payne v. Major League Baseball. Payne filed an Amended Complaint (adding two plaintiffs and now naming all Major League Baseball teams as defendants). Major League Baseball filed a Motion to Dismiss. The Motion is fully briefed and the court was scheduled to hear oral argument on March 22.

The briefs are lengthy and MLB raised numerous arguments, generally related to the plaintiffs having no Article III standing (plaintiffs fail to adequately allege a concrete and particularized injury that is imminent), lack of personal jurisdiction against the non-California teams; venue issues (most of the teams are not located in the Northern District of California) and failure to allege the necessary elements for the asserted causes of action.

I raised the plaintiffs’ “lack of standing” in my Wall Street Journal Op-Ed. That’s not a brag. Lack of standing here is so obvious that My Cousin Vinny could have figured it out.

The most interesting development in the case, as pointed to by the plaintiffs, is that in December 2015, Major League Baseball, after an in-depth study, issued recommendations concerning fan safety, including this one: “Clubs are encouraged to implement or maintain netting (or another effective protective screen or barrier of their choosing) that shields from line-drive foul balls all field-level seats that are located between the near ends of both dugouts (i.e., the ends of the dugouts located closest to home plate, inclusive of any adjacent camera wells) and within 70 feet of home plate. The Commissioner’s Office has retained a consultant specializing in stadium architecture and protective netting to assist interested Clubs in implementing this recommendation.”

I believe that the plaintiffs’ case is a hail Mary and a slam dunk for Major League Baseball. But if my NCAA Tourney bracket is any indication of my predictive skills….

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

What Do You Buy When An Umbrella Still Doesn’t Provide Enough Protection?

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

I’ve Never Seen This Before:

Is Agent Liable Because It “Should Have Tried Harder” To Get A Claim Paid?

|

|

|

|

| |

Claims by insureds, against their agents, for failing to obtain insurance that covered a claim, are fairly routine. There are challenges for insureds to prevail in these situations. However, it is not impossible either. The Arizona Court of Appeals, in Delicious Deliveries Phoenix, Inc. v. BBVA Compass Insurance Agency, Inc., No. 1-CA-CV 14-0585 (Ct. App. Az. Feb. 16, 2016) recently addressed a different type of claim by an insured against its agent – for failing to serve as an advocate to get a claim covered. This is an “agent claim” that I’ve never seen made before.

BBVA Compass Insurance Agency, Inc. assisted Delicious Deliveries Phoenix, Inc. in obtaining an insurance policy from Auto–Owners. “Compass thereafter submitted two property-loss claims to Auto–Owners on Delicious’s behalf—one related to an alleged equipment breakdown and one related to an alleged employee theft. Using preprinted forms, Compass provided brief descriptions of the claims (specifically, ‘Insd phone equipment was [out] for over 3 weeks and had significant loss as well as business interruption’ and ‘insd employee [as named]—stole from the insd. employee dishonesty claim’), and identified available coverages and limits.”

Auto-Owners ultimately denied both claims. Delicious turned around and filed an action against Auto-Owners and Compass asserting a host of claims. Putting aside lots of detailed allegations, one claim against Compass was based on a “claims-advocacy theory.” Delicious asserted that “Compass failed to ‘d[o] anything to assist its customer’ when it ‘inserted itself into the process of adjusting the claim,’ and generally failed to ‘do a good job of it .’”

At the heart of Delicious’s claim was an Auto–Owners employee’s deposition testimony that “insurance agents ‘[a]bsolutely’ can advocate for their clients, and that such efforts may affect an insurer’s coverage determination ‘if [the] insurance agent has additional information that ... may change a coverage position.’”

The trial court entered summary judgment in favor of Compass. Delicious, being left with a bad taste in its mouth, appealed.

The appeals court’s decision is less than clear. However, importantly, the court seems to have said that an agent has a duty to serve as a claims advocate. But, here, “Delicious provided no evidence—expert or otherwise—that a reasonable insurance agent in Compass’s position should have and would have acted differently with respect to claims advocacy.”

The court noted that the deposition testimony of the Auto-Owners’s employee established that “an insurance agent may serve as a conduit for the factual information on which an insurer bases its coverage decisions.” However, as the court saw it, “Delicious did not allege that Compass failed to relay factual information to Auto–Owners; Delicious’s theory was instead that Compass should have acted as a more aggressive advocate.”

In summary, the court held: “It is not sufficient merely to point to the fact that coverage was denied to support an inference that an agent breached a duty—a plaintiff must identify evidence that shows what the agent should have done or not done. A general assertion that the agent should have tried harder is not evidence of negligence.”

Lastly, while the court acknowledged that expert testimony was not needed by Delicious, as it was pursuing a claim for general negligence, and not professional negligence [not sure I get that], “[e]xpert testimony identifying precise failings by Compass would no doubt have been helpful to Delicious.”

Delicious Deliveries Phoenix, Inc. v. BBVA Compass Insurance Agency should be a cautionary tale for agents. Here, the agent prevailed because Delicious did not allege that Compass failed to relay factual information to Auto–Owners. Delicious did not identify evidence that showed what Compass should have done, or not done, to get the claim paid. But suppose Delicious did – and with expert testimony -- identify evidence that shows what Compass should have done?

Granted, if the claim wasn’t covered, under any circumstances, then the agent should be relieved of liability, because there is nothing that it could have done. But what if the claim could have been covered – it just needed someone to explain why, based on either additional facts, a better presentation of the facts or a challenge based on case law, or a combination of these? Has this court opened the door to insureds, to make claims against their agents, that they didn’t act, essentially in the role of coverage counsel, to challenge a claim denial?

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

What A Difference The DOJ Makes: Court Upholds Specific Claims Exclusion

|

|

|

|

| |

It is pretty unusual for a court to grant a motion for reconsideration. And, by definition, it is unlikely for the court to do so in a not-breaking-a-sweat fashion. But that’s what happened in Millennium Laboratories, Inc. v. Allied World Assurance Company, No. 12-2280 (S.D. Cal. Feb. 25, 2016). It wasn’t easy for the insurer to reach that point. But it was persistent -- and rewarded for it.

At issue was coverage for Millennium Laboratories, under a Directors and Officers Liability Policy issued by Allied World in late 2011. At the time that the policy was issued, Millennium was, in the court’s words, “facing problems.” The court noted that “[s]everal competitors had filed private lawsuits and several whistle-blowers had filed qui tam actions against Millennium. These lawsuits alleged that Millennium engaged in unlawful business practices, that it encouraged health care providers to submit false and/or fraudulent claims to health insurers and that it provided unlawful kickbacks to those health care providers.”

The court explained that the policy was issued with Allied World wanting to exclude actions that had culminated in lawsuits already filed (avoid insuring the proverbial burning building, in the court’s words) and Millennium wanting protection from future lawsuits. The result, the court stated, was a “[p]olicy negotiated by top-notch lawyers.”

Enter the Department of Justice. The DOJ, as part of an investigation of any illegal activities by Millennium, issued broad subpoenas, seeking a “wide range of documents and listing a wide range of potential offenses.” Millennium sought coverage from Allied in responding to the subpoenas.

Allied said no so fast, pointing to the “Specific Claims Exclusion” in the policy: “No coverage will be available for Loss from any Claim based upon, arising out of, directly or indirectly resulting from, in consequence of, or in any way involving” the Ameritox Action, the Aegis Action, and the Robert Cunningham Action.

In late September 2015, the court granted Millennium’s and denied Allied’s Motion for Summary Judgment. As the court explained: “At that point in time, since the DOJ investigation was shrouded in Grand Jury investigation secrecy, it was impossible to determine whether the investigation or allegations being investigated arose out of, were based upon, or were attributable to prior actions or to wholly new conduct.”

But shortly thereafter the lid came off the DOJ’s activities – revealing a previously sealed complaint filed by the DOJ against Millennium, as well as a settlement agreement. Almost a month to the day after Allied’s motion for summary judgment was denied, the insurer marched back to court, filing a motion for reconsideration.

In other words, in light of the information learned about the DOJ’s activities, the insurer sought to have the court reconsider whether the Specific Claims Exclusion applied. Was there now enough information to establish that the DOJ investigation was based upon, arising out of, directly or indirectly resulting from, in consequence of, or in any way involving the prior suits involving Millennium?

The court set out the standard for granting a motion for reconsideration based on newly discovered evidence: “(1) the evidence was discovered after the court’s judgment was issued: (2) that even with due diligence the evidence could not have been discovered earlier; and (3) that the newly discovered evidence is of such a magnitude that had the court known of it earlier, the outcome would likely have been different.”

Without question the evidence was discovered after the court’s ruling denying Allied’s motion for summary judgment. And even with due diligence the evidence could not have been discovered earlier by Allied. After all, it had been sealed in a federal zip-lock bag. Turning to whether the newly discovered evidence was of such a magnitude that, had the court known of it earlier, the outcome would likely have been different, the answer was yes: “A quick review of the three Actions listed in the Specific Claims Exclusion and a comparison of the Settlement Agreement makes it clear that this exclusion applies. [The actions] were lawsuits filed by a Millennium competitor alleging that ‘Millennium formed a business plan to increase its market share...through an improper and illegal scheme’ including illegal kick-backs and encouraging false billings to Medicare. These are exactly the same allegations listed in the Complaint filed by the DOJ against Millennium and Settlement Agreement entered into between the parties.”

The court went on and provided specific examples to support its conclusion, as well as rejecting arguments by Millennium, that the DOJ complaint alleged “separate wrongs” from what was alleged in the actions listed in the “Specific Claims Exclusion.”

Held: “Had the Court known of the Settlement Agreement at the time it issued its Order regarding Summary Judgment Motions, its Order would have been different. At the time the Order was issued, Allied World had failed to prove that the Department of Justice investigation ‘in any way involved’ any of the actions listed in the specific claims exclusion. They have now done so.”

If at first you don’t succeed, trial trial again.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

Appeals Court Addresses Cyber Coverage

|

|

|

|

| |

There has been oodles of discussion over the past couple of years about cyber coverage. But what there has not been are judicial decisions addressing the issues. For this reason, when a case comes down on the subject of cyber coverage, it usually takes on more significance, and gets more attention, than it would if there were a more fuller developed body of law in the area. These days, a Justice of the Peace in South Dakota could issue a decision about coverage for a breach of the Commodore 64 at Cletus’s Feed Store and it would be news. So, needless to say, an opinion from the New York Appellate Division cannot go unnoticed.

As is not unusual for an opinion from the New York Appellate Division, RVST Holdings, LLC v. Main Street America Assurance Co. (N.Y. App. Div. Feb. 18, 2016) is brief. I’ve seen CVS register receipts, for a pack of Chiclets, that contain more words than New York Appellate Division decisions. But, in this case, the opinion didn’t need to be any longer than it was.

In RVST Holdings, the New York Appellate Division, Third Department, addressed coverage under the following circumstances. RVST Holdings was an operator of fast food restaurants that stored its customers’ credit card information on its computer network. The court further described the situation: “The network was infiltrated by unknown individuals who unlawfully obtained the customers’ card information and then used that information to make numerous fraudulent charges. Nonparty Trustco Bank subsequently commenced an action against [RVST Holdings] that alleged, as relevant here, that plaintiffs had negligently failed to exercise reasonable care in safeguarding the information of Trustco cardholders, which, in turn, caused Trustco to sustain damages related to its reimbursement of the fraudulent charges. [RVST Holdings] then sought coverage under their business owner’s insurance policy issued by defendant [Main Street America Assurance]. After an investigation, however, [Main Street America] declined to defend or indemnify plaintiffs in the underlying Trustco action, asserting that the policy excludes from coverage third-party claims arising out of the loss of electronic data.”

For reasons not explained by the Appellate Division, the trial granted summary judgment for RVST, holding that Main Street America had a duty to defend. Main Street America appealed and the Appellate Division reversed. And it didn’t struggle to reach its decision.

First, there was no dispute between the parties that Trustco’s complaint was based upon “losses due to the theft and subsequent misuse of electronic account data and/or electronic vandalism at certain [of plaintiffs’ restaurant] locations.” Nor was “there any dispute that the electronically stored cardholder information at issue in the underlying action qualifies as ‘electronic data’ under the policy’s definition of that term.”

With that as the foundation, the court turned to the principal policy provisions: The insurer “will pay those sums that [RVST] become[ ] legally obligated to pay as damages because of ... ‘property damage.’ ‘The policy defines ‘property damage’ as ‘[p]hysical injury to tangible property ... or ... [l]oss of use of tangible property that is not physically injured.’”

However, as the court noted, “crucially” -- and, indeed, it was crucial -- the policy stated that, “‘[f]or the purposes of this insurance, electronic data is not tangible property.’ Moreover, the policy specifically excludes ‘[d]amages arising out of the loss of ... electronic data.’”

Based on this “unambiguous language,” the court held that Trustco’s claim, for damages arising out of RVST’s negligent handling of electronic data, is not a claim for “property damage” and is excluded from coverage. Therefore, the New York Appellate Division reversed, holding that the insurer had no duty to defend RVST against Trustco’s claim.

In case you’re wondering what RVST argued in support of coverage, it was this: The policy also contained a separate section providing coverage for property damage. However, as the court pointed out, this section provides coverage for “direct physical loss of or damage to” plaintiffs’ own property. “Unlike the liability section of the policy, for which plaintiffs paid a separate premium, the property damage section contains no language indicating that it covers the claims of third parties. Thus, the property damage section of the policy provides only first-party coverage for direct damage to plaintiffs’ property, a claim not made by plaintiffs here and, further, one that ‘does not involve any need or duty to provide the insured with a legal defense.’”

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

Insurer Does Not Use ISO Policy Language -- And Pays $5.4 Million

|

|

|

|

| |

Lee v. Universal Underwriters Insurance Company, No. 14-13345 (11th Cir. Feb. 11, 2016) should have been an easy win for the insurer. In fact, so easy that coverage litigation should not have even been brought. And that surely would have been the case if the insurer’s policy had simply used certain tried and true language from a general liability policy. But, instead, the insurer’s policy went off the board. And the insurer paid dearly for it’s creativity- $5.4 million.

The claim is straightforward. In June 2005 Darris Lee had his 2000 Ford Expedition repaired at Terry Holmes Ford. The speed control switch was replaced. On December 11, 2008, Lee was driving the car, with Harold Brenner as a passenger, when he tried to brake as he approached slowing traffic. Lee was unable to stop or slow down. To avoid a collision, he drove onto the grass shoulder. The vehicle rolled over several times. Lee died at the scene and Brenner suffered severe injuries. It was later determined that, during the 2005 repair, the technician bent and damaged the cruise control cable. This eventually caused the vehicle’s throttle to stick open, which caused Lee to lose control of the vehicle.

In June 2005, when the vehicle was repaired, Terry Holmes Ford was insured under a liability policy issued by Universal Underwriters. However, the policy went off the risk on June 1, 2007, a year and a half before the accident.

Under the language contained in the standard ISO commercial general liability policy, this is a hot knife through butter claim for the insurer. Under that form, coverage is only provided for “bodily injury” that takes place during the policy period. Here, as noted, the “bodily injury” took place well outside of the policy period.

However, in Lee, the insurer’s policy used different language than what appears in ISO’s form. The policy provided:

"INSURING AGREEMENT—WE will pay all sums the INSURED legally must pay as DAMAGES . . . because of INJURY to which this insurance applies caused by an OCCURRENCE arising out of GARAGE OPERATIONS or AUTO HAZARD.

The policy defined an “occurrence” as: “OCCURRENCE”, with respect to COVERED POLLUTION DAMAGES, INJURY Groups 1 and 2 means an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to conditions, which results in such INJURY or COVERED POLLUTION DAMAGES during the Coverage Part period neither intended nor expected from the standpoint of a reasonably prudent person.”

The insurer disclaimed coverage for the Lee and Brenner suits filed against the Ford dealer. Its basis was that the December 2008 accident fell outside the policy period, which ended in June 2007. The claimants entered into a combined settlement with the dealership, for $5.4 million, in exchange for an assignment of policy rights. The claimants filed suit against the insurer. The federal district court found in favor of the claimants. An appeal was taken to the Eleventh Circuit.

The Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that “the policy covered the ‘occurrence’ of the negligent repair that took place during the coverage period, even though the injury did not manifest until after the coverage period.”

The court’s explanation is not a model in clarity: “We agree with the district court that the policy’s plain text is ambiguous about what type of ‘occurrence’ triggers coverage. The policy does not clearly state that it applies only to injuries that occur within the policy period, nor does it state specifically what type of ‘accident’ during the policy period might trigger coverage. The policy also identifies an ‘injury’ as a distinct concept from an ‘occurrence’ or ‘accident’ for coverage purposes, suggesting that the ‘occurrence’ trigger for coverage is not the same as the time of the injury. We hold, as the district court did, that the policy could reasonably be interpreted as requiring either that the accident—here, the negligent repair—occur during the policy period, or that the injury resulting from the accident—here, the car crash—occur during the policy period.”

I believe that the decision was wrongly decided. Even under the policy’s non-traditional definition of “occurrence,” I see only a requirement that there must be injury during the policy period. However, the policy’s use of the definition of “occurrence” that it did opened the door to a decision that it was ambiguous. Again, under the plain old ISO general liability policy language, which does not define “occurrence” in terms of timing, and which makes clear that coverage is only provided for “bodily injury” that takes place during the policy period, I can’t see how the insurer loses this case. Sometimes boring is good.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 4

March 30, 2016

Late Notice: Supreme Court Says Notice To Broker Could Be Notice To Insurer

|

|

|

|

| |

It is not unusual to see an insured challenge a late notice disclaimer on the basis that its notice wasn’t late at all. To the contrary, the insured says that it provided notice a very short time after the insured became aware of the incident or claim. However, such notice wasn’t provided to the insurer, but, rather, to the insured’s broker. And it turns out that the broker didn’t pass along such notice to the insurer. The insurer’s response to this will likely be that it has no relationship with the broker, so, therefore, notice to the broker does not qualify as notice to the insurer. In other words, the broker is not authorized to accept notice on the insurer’s behalf. Hence, as far as the insurer is concerned, by the time it actually received notice of the claim, a long time had passed and it was not timely, i.e., the notice provision in the policy was breached.

[Of course, with the usual requirement that, for “occurrence” policies, an insurer must prove that it was prejudiced by an insured’s untimely notice, which can be difficult, the significance of notice to a broker is most likely to be relevant in the few “no prejudice” states, in situations where the delay is really long, and in the context of “claims made” policies, where prejudice is not usually a factor to establish a violation of a notice provision.]

In Southern Cleaning Service, Inc. v. Essex Insurance Company, Nos. 1140970 and 1140918 (Ala. Feb. 19, 2016), the court addressed whether an insured could defeat a late notice challenge on the basis that it provided immediate notice of an incident to its broker -- and the fact that the insurer, itself, did not receive notice until much later is not relevant.

A company called Phase II Maintenance Systems had a subcontract to provide janitorial services to Winn-Dixie grocery stores. As part of the arrangement, Phase II was required to obtain insurance and name Winn-Dixie and Southern Cleaning Service, Inc. (SCSI), the main contractor, as additional insureds. Phase II got in touch with Alabama Auto Insurance Center, an independent insurance agency, to obtain the insurance it needed. Alabama Auto turned to Genesee General Agency, a managing general agent that connects independent agents with insurers. Genesee obtained a quote from Essex Insurance Company for a policy to meet Phase II’s needs. Phase II accepted the quote. Genesee, which had Essex’s authority to do so, issued the Essex policy to Phase II.

On March 5, 2011, “Beverly Paige was shopping at a Phase II-serviced Winn–Dixie in Montgomery when she allegedly slipped on a wet floor, fell, and was injured. A Phase II employee on duty at the store at the time of the fall reported the incident to Phase II’s owner and president, William Wedgeworth, that same day, and Wedgeworth has given sworn testimony indicating that he separately notified both SCSI and Alabama Auto of the incident on Monday, March 7, 2011, and further specifically asked Alabama Auto to notify Genesee of the incident.”

To make a long and winding story short, notice of the claim did not get to Essex until June 2012. Essex disclaimed coverage based on late notice: “Essex had not been notified of the claim until approximately 15 months after Paige’s fall, notwithstanding the fact that the Essex policy obligated the insureds to notify it ‘as soon as practicable’ of any occurrence ‘which may result in a claim.’ … On September 25, 2012, Paige sued Phase II, SCSI, and Winn–Dixie, alleging that their negligence and wantonness was responsible for the injuries she sustained in her March 5, 2011, fall. Phase II, SCSI, and Winn–Dixie again asked Essex to provide them with a defense and indemnity under the terms of the Essex policy; however, their requests were denied.”

A settlement of the Paige action was eventually reached for $540,700. Putting aside a lot of procedural and extraneous issues, the principal issue before the Alabama high court was whether Essex could maintain its late notice defense based on the 15 month delay before it received notice. [Alabama is a no prejudice state.]

The argument against Essex was that “Alabama Auto was notified of Paige’s accident within days of its occurrence and, SCSI argues, Alabama Auto had either real or apparent authority to accept notice of claims on behalf of the insurance defendants [Essex and Genesee].”

It was not disputed that Alabama Auto was not an agent in fact for Essex and Genesee. The relevant contracts, discussing the parties’ relationships, bore this out. The issue was whether Essex and Genesee “cloaked Alabama Auto with the apparent authority to accept notice of claims on their behalf.” On this point, the court, while making clear that nothing was conclusively established, had little difficulty concluding that substantial evidence of genuine issues of material fact existed. There were three reasons for the court’s conclusion that summary judgment for the insurer defendants was improper.

The declarations page of the Essex policy listed Alabama Auto as “agent” – but with no further description. The court concluded: “[W]e note that a fair-minded person could reasonably understand the Essex policy to be referencing Alabama Auto as a dual agent or as the agent of the insurance defendants in some limited respect.” Further, “the fact that the insurance defendants issued an insurance policy without placing their own contact information on that policy further indicates that Alabama Auto-whose contact information was provided on the policy-had some authority to serve as the proper conduit for communication between the insureds and the insurance defendants.”

Second, Phase II’s owner’s sworn testimony indicated that he never had any direct dealings with Essex or Genesee. All communications, including premium payments, went through Alabama Auto.

Third, the insurance defendants accepted and responded to notices of claims forwarded to them by Alabama Auto on behalf of Phase II in other cases. As the court saw it, “if the insurance defendants had not accepted the notice provided via Alabama Auto in subsequent cases, or had at least told Phase II, SCSI, or Winn–Dixie that notice provided in such manner was improper, that would have apprised those parties that they needed to give notice of claims directly to the insurance defendants in all cases, including Paige’s. They might then have been able to provide direct notice of Paige’s claim more than 15 months before they actually did so, instead of continuing to operate under a belief that Alabama Auto had the authority to accept notice on behalf of the insurance defendants.”

As I see it, the biggest lesson from Southern Cleaning Service for insurers, that do not wish to face an apparent authority argument concerning notice, comes from the Dec Page. Listing Alabama Auto as “agent” – but with no further description – and then providing Alabama Auto’s contact information, but not Essex’s, gave the court an easy opportunity to make hay.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Allocation Does Not Violate Public Policy

Cases addressing whether a provision in an insurance policy violates public policy often make for interesting reading. Putting aside coverage for punitive damages, where the argument is sometimes successful, courts are usually not convinced that a policy provision, or something about the policy, violates public policy. This was the conclusion in Housing Authority of New Orleans v. Landmark Insurance Company, No. 15-1080 (E.D. La. Feb. 29, 2016), where the court held that an Allocation clause, in a D&O policy, did not violate Louisiana public policy. The Allocation clause “addresses situations in which a plaintiff brings a claim against the insured that includes covered and non-covered matters, covered and non-covered causes of action, or covered and non-covered parties. In such a situation, the insured and the insurer are required to use their best efforts to allocate defense expenses to the covered and non-covered claims.”

The court noted that, under Louisiana law, “when an insurer has a duty to defend any claim asserted, the insurer must defend the entire action brought against its insured.” Further, the court observed (and not surprisingly): “This concept has been reiterated over and over by Louisiana courts.” However, the court concluded that “the obligation to defend is a contractual one, indicating it is not absolutely guaranteed by state policy” and that Louisiana law would support this contractual limitation on the duty to defend.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|