|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

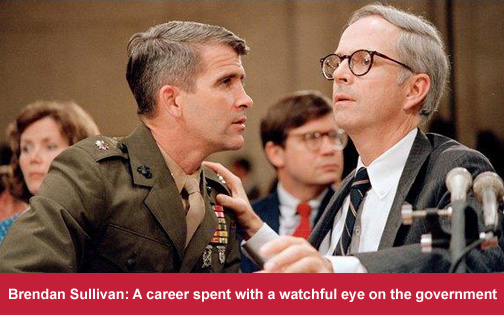

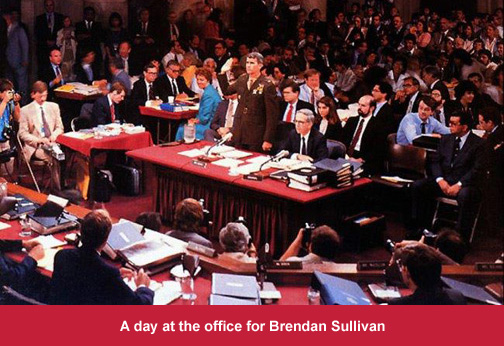

Nearly three-quarters of the United States saw part of the Iran-Contra hearings on television in 1987. Eight years before the nation was gripped by a bloody glove, it came to a stand-still to watch a Marine Lt. Colonel tell the joint House--Senate Iran Contra Committee what he, and others, knew about a secret U.S. sale of arms to Iran -- with the use of proceeds to fund the Contras in Nicaragua. The soldier was Oliver North. Sitting to his left was Brendan V. Sullivan, Jr., his just-turned 45 year-old lawyer. Bespectacled in schoolboy frames, Sullivan protected North like a mother bear her cubs.

|

|

|

|

|

Those six days on television made Brendan V. Sullivan famous. But it took a lot more than the Iran-Contra hearings, and even being named ABC World News “Person of the Week” afterwards, for the Legal Times to declare Sullivan the “Best Counsel Available” in Washington and the Washingtonian to call him D.C.’s “Toughest Lawyer.” And this is a town with more lawyers than Dijon has mustard. These accolades were earned by Sullivan spending the next 30 years working to shield many more clients from attacks by the government. He has reportedly been described by peers as the courthouse equivalent of a nuclear war. The glasses are fitting. Brendan Sullivan has spent a career taking prosecutors to school.. |

|

|

|

| |

While the D.C. legal community has named Sullivan “The Leading Lawyer in White Collar Criminal Defense,” his practice is far from one-dimensional. The senior partner at venerable Williams & Connolly – and protégé of its founder, the legendary Edward Bennett Williams - also handles a variety of complex and high-profile civil matters. Indeed, Brendan V. Sullivan’s litigation practice is so extensive that his first name has even sued his last.

I’ve been an admirer of Brendan Sullivan for a long time. I was glued to the Iran-Contra hearings. In 1991 I met Oliver North at a signing for his just-released autobiography Under Fire. I told North that I had recently graduated from law school and asked him if he could get me a job with Sullivan. North laughed it off. He signed my book: “Randy, All the best in the law.” That was the extent of Oliver North’s assistance in my career.

Well, twenty-five years later I finally got my interview with Brendan Sullivan. There were many subjects I could have focused on. I chose the one that made him a household name -- his ferocity to protect his clients from the power, and sometimes unlawful tactics, of the government. It’s not a secret that the government sometimes gets called out for prosecutorial misconduct. Sullivan has spent a career protecting clients from such abuse. And in several cases he has laid it out for all to see -- including the granddaddy of them all. About that one Sullivan offers a sobering lesson.

I was delighted when Brendan Sullivan agreed to speak with me (especially with at least three news stories saying that he rarely gives interviews). But, as the hour to call him approached (he’s so senior at Williams & Connolly that his direct-dial phone number ends with 5800), I began to regret my decision. The knot in my stomach would have impressed an Eagle Scout. I’ve had the privilege of interviewing many of the most famous lawyers in America. I get nervous before every one. You would too. But Brendan Sullivan took it to another level. I couldn’t rid my head of the images of him, during the Iran-Contra hearings, practically turning the inquisitors into witnesses. But Sullivan could not have been nicer. He was generous with his time and forthcoming with his answers. And, unlike the Iran-Contra hearings, didn’t object to any questions.

Keeping The Government Honest

Prosecutors are out to prove if the defendant did it. For Brendan Sullivan that is just part of the case: “[Prosecutors],” he told me, “have such enormous power over life, death, freedom, or not freedom, that they have to play by the rules.” Making sure that they do so is Sullivan’s business. He described unambiguously what it looks like when they don’t: “[I]t’s a frightening and sickening experience when you see misbehavior by government officials in the criminal context.”

Oscar Goodman, the legendary mob lawyer turned Las Vegas Mayor, says this right off the bat in his autobiography, Being Oscar: “Over my forty-year career as a defense attorney, I regularly came into contact with people who lied, cheated, and tried to bend the system so they would come out on top. Most of them worked for the government. *** In almost every case I tried – and I tried hundreds – Federal prosecutors and FBI agents thought nothing of withholding evidence, distorting the facts, or making deals with despicable individuals who would get up on the witness stand and say whatever they were told.”

I read this passage to Sullivan and asked him: Is it really this bad? Yes and no, Sullivan said. He called Goodman’s description “pretty accurate,” but doesn’t see misconduct being nearly as pervasive. Sullivan told me that he is “always the first to say that certainly 90%, maybe 95%, of all prosecutors are good people, well trained, wanting to do justice, wanting to do the best, wanting to protect the community.” But Sullivan was quick to add that “the sad fact is I have run into a half a dozen cases which are notorious for having corrupt government actions -- lawyers acting unethically, indeed criminally, in order to win a case and that is a frightening prospect.”

Sullivan recounted for me attending a fundraiser for The Innocence Project – the organization famous for winning exonerations of wrongly convicted individuals. He described a line of people on stage, each stating their name and how many years they served in jail for a crime they didn’t commit. “I mean you cry,” Sullivan said.

I wondered if prosecutors work harder to beat Brendan Sullivan, thinking it’s a feather in their cap to say that they did? Sullivan told me he hopes that’s not the case -- but he acknowledged that prosecutors might have a reason to work harder against him. “I think they try hard to beat us because the kinds of cases we get, they’re more interested in. They’re more high visibility. And in some cases they might think that winning this case will lead to promotions, to judgeships, to jobs in the big law firms. They can say ‘I was the prosecutor in the [Ted] Stevens case.’ It is quite common for prosecutors to tout their victories and to use the victories as stepping stones.”

In a PBS interview, Sullivan expanded on this idea, crediting reputational concerns as a reason why a prosecutor might turn bad. He explained that when a prosecutor reaches a point in a case where he or she feels that they could lose, and that would be bad for them professionally, their competitive nature may take over and they may “cheat to win.”

Sullivan also rails against other flaws in the system. That prosecutors are almost never punished for engaging in misconduct is at the heart of the problem he says. In addition, he tells me, on account of the trial penalty – a defendant receiving a harsher sentence after being found guilty than if he or she had pled guilty – “one wonders whether a criminal trial is a viable option for anyone.” Sullivan called it “horrifying,” to criminal defense lawyers of his generation, “to see the disappearance of the criminal trial.”

Sullivan’s introduction to government overreach came very early in his career. He was stationed in San Francisco during the Vietnam War. Despite the 1964 Georgetown Law grad serving as a supply officer, Sullivan, Captain, was asked by prisoners in the Presidio stockade to represent them concerning overcrowded conditions. In the process, Sullivan encountered a system that denied his clients their rights. He fought back, refusing to go along to get along. The Army decided that the way to silence Sullivan was to send him to South Vietnam for the last six months of his tour. The story got the attention of The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite and others in power. At the last minute Sullivan’s retaliatory deployment was blocked by the Secretary of the Army.

The extent of prosecutorial misconduct was the subject of a 2010 story in USA Today, reporting on the findings of the newspaper’s six month investigation into the subject. In 1997, Congress enacted a law designed to end prosecutorial abuses. According to the paper, it documented 201 criminal cases, since that time, where judges determined that Justice Department prosecutors violated laws or ethics rules.

The Justice Department sees it differently. As reported in the USA Today story, the DOJ’s internal ethics office insists that it happens rarely (the adverb “rarely” is not reflected as a DOJ quote; but USA Today’s description of the DOJ’s characterization). According to Justice’s Office of Professional Responsibility, 750 investigations, undertaken over the decade prior to the story, found intentional violations in 68 of them. [Readers can choose their own adverb.] The DOJ would not identify for USA Today the cases that had intentional violations and it removes from public reports any details that could identify the prosecutors involved.

USA v. Senator Ted Stevens: If It Can Happen Here…

Oscar Goodman uses a startling description to make his point about prosecutorial misconduct. Sullivan has one of his own. It comes out of the government’s prosecution of Senator Ted Stevens (R- Alaska).

In July 2008, Ted Stevens was charged in a seven count indictment with making false statements. Specifically, he allegedly failed to report, on his Senate Financial Disclosure Forms, gifts he received from Bill Allen, CEO of VECO Corp., and others, including renovations of his home in Alaska. Stevens was represented by Sullivan and a team from W&C. In late October 2008, Stevens was found guilty by a jury on all seven counts. Bi-partisan calls for Stevens’s resignation were immediate. It was a moot point because Stevens lost his re-election bid shortly thereafter.

What happened post-conviction is complicated. But the short story goes like this. In February 2009, an FBI agent filed a whistleblower affidavit, alleging that prosecutors and FBI agents conspired to withhold and conceal evidence, including notes taken by prosecutors during an interview of Mr. Allen. But that wasn’t the only problem for the government in the case. Stevens’s defense team pointed out that, “over and over” the government was caught in false representations and otherwise failing to perform its duties under the Constitution and rules. And, in each instance, the defense said, the government sought to explain it away as a mistake or a mistaken understanding or not done in bad faith or inadvertent or unintentional or immaterial.

In one instance, the court became so exasperated by its inability to get a “cohesive or credible answer” from the government, concerning an aspect of the whistleblower complaint, that it ordered the Attorney General himself to sign a declaration, under oath, detailing who within the DOJ knew certain details about it, as well as what and when. I asked and Sullivan told me that he had never seen another instance of a judge compelling any Attorney General to do something like that. [The Court ultimately reconsidered, because of the demands on the A.G.’s time, and agreed to allow a high-ranking designee to file the declaration.]

It all came to a head in April 2009 when the court granted the government’s Motion, brought by a newly-appointed team of prosecutors, to Set Aside the Verdict and Dismiss the Indictment. The government had conceded that the notes from the Allen interview contained information that it was constitutionally required to provide to the defense for use at trial. However, the court stated that “[d]espite repeated defense requests and the Court’s repeated admonitions to provide exculpatory information, the notes were not produced to the defense until March 25–26, 2009, nearly five months after trial.” [Sadly, Senator Stevens died a year later in a single engine plane crash in Alaska.]

As Sullivan sees it, the lesson to be learned from the Stevens case is clear -- and staggering: “You have a U.S. Senator, a sitting senator, a powerful senator with a lot of friends, be indicted in the nation’s capital, and have the case tried in one of the finest District courts in the country, with a very experienced, smart federal judge. And you have the top prosecutors, the elite of prosecutors, lined up to bring the case, to try the case, and, modestly, you have experienced defense counsel right here in the city, known for their successful criminal defense work. If in [a well defended case, right here in the District of Columbia] you can have illegal conduct by the government, perjury by government witnesses, hiding of evidence [failing to give Brady material which clearly exculpates the defendant], what’s going on in the rest of the country? . . . It’s a frightening prospect so the lesson of the Stevens case is, of course, if it can happen here, under these circumstances, it can happen anywhere.”

Sullivan wouldn’t call the Stevens case his most satisfying win – simply because, he told me, there is great professional satisfaction every time you save someone. But he said that the Stevens victory does stand above others in one way. While all cases involve a human element -- saving a person whose life is in jeopardy -- the Stevens case, he hopes, will have an impact on the system.

A Career Carrying Brandy

Sullivan joked that lawyers who do his kind of work are like a St. Bernard, carrying a cask of brandy up a snow covered mountain to save a skier. Sullivan has carried a lot of brandy.

Sullivan, working behind the scenes with the local lawyers, represented Duke University lacrosse players who were accused of rape, sexual assault and kidnapping of an exotic dancer at a party. The North Carolina Attorney General, following findings of prosecutorial misconduct, ultimately dismissed the charges and announced that the plaintiffs were in fact innocent. Sullivan’s involvement surfaced when he represented the players in a civil rights action brought against the City of Durham, North Carolina.

Sullivan represented Dr. Henry Nicholas, co-founder of Broadcom, who was accused of fraud concerning the backdating of options. The case was dismissed. Pacer does not include the transcript of the dismissal hearing, but, in doing so, the Judge reportedly accused the prosecution of a “shameful” campaign of witness intimidation aimed at securing unjustified convictions.

Sullivan represented Richard Grasso, Chairman and CEO of the New York Stock Exchange, against the State of New York, which accused Grasso of receiving an excessive compensation package. It totaled nearly $140 million. Maybe it’s hard to feel sorry for Dick Grasso. But even rich people are entitled to a defense against government overreach. The case reached the New York Court of Appeals. Without getting into the weeds (and this wasn’t the only case), the New York Attorney General did not prevail. While the state’s highest court suggested that the compensation package may seem unreasonable on its face, Sullivan beat back the challenge on the grounds that the A.G. lacked the authority to do so. Just as in his criminal cases, Sullivan succeeded by challenging the government’s method.

Sullivan has also represented several state attorneys general, against Microsoft, involving antitrust violations; FBI agents involved in the 1992 Ruby Ridge shootout; and former HUD Secretary, Henry Cisneros, against accusations of making false statements to the FBI during a background check.

Studying Sullivan’s career I couldn’t help but think that he should write a book detailing his experiences with prosecutorial misconduct. While there is certainly literature out there on the subject, surely a book by Brendan Sullivan would get a lot of attention. But Sullivan has no interest he tells me. It turns out that I’m not the first person to make this suggestion. So his response is well-rehearsed. He won’t do what it takes to meet the criteria for a book by a lawyer – tout his own success and tell secrets.

Iran-Contra

I didn’t ask Sullivan about the Iran-Contra hearings. It is an old and well-known story. But in Under Fire, Oliver North tells a story about Sullivan that demonstrates his ferociousness to protect his client.

Months before North testified, Sullivan told him that he’d have to take the Fifth Amendment. But North had no interest in doing so. As North saw it, the Fifth Amendment was for criminals. It was for people with something to hide. It was tantamount to pleading guilty. North said he was proud of what he did. According to North, Sullivan replied, “I know you are. But that’s not what you’re going to do.”

North recounts what Sullivan said next: “If you and I were in a plane that crashed in a jungle behind enemy lines, and we were fortunate enough to survive, I’d rely on you to get us out of there alive. Well, today you’re in a different kind of jungle, and you’ve got to rely on me. You may not like everything I tell you to do, but as long as I’m your lawyer, that’s the way it’s going to be.”

Sullivan was, of course, concerned about a possible criminal prosecution of North down the road, and making sure that nothing North said, before the House-Senate committee, would be used against him in any such proceeding. North eventually testified before the Committee with use immunity, precluding anything he said from being used against him in a criminal case. Sure enough, North was criminally charged -- and found guilty. And sure enough, Sullivan had the conviction overturned, on grounds that the government used North’s immunized testimony against him.

I’m Not A Potted Plant

By now the story is the stuff of lawyer-legend. It will be told in Sullivan’s obituary – maybe even the first paragraph. If not, definitely the second.

During the Iran-Contra hearings, Hawaii Senator, and Committee Chair, Daniel Inouye admonished Sullivan for objecting to a hypothetical question posed to North by Arthur Liman, Chief Counsel of the Senate committee. [“Dreamland. Pure speculation. It has two ‘ifs’ in it,” Sullivan protested, arms wide apart.] Following a heated exchange between Inouye and Sullivan, the chairman stated that North can object himself if he wishes. Sullivan, with an incredulous expression, responded: “Well, sir, I’m not a potted plant. I’m here as the lawyer. That’s my job.”

Sullivan’s words elicited huge laughter from the gallery and “I’m not a potted plant” took on a life of its own. Whatever people thought about North (and he had detractors), the line endeared Sullivan to the public as a lawyer who wouldn’t back down. In Under Fire, North described what happened later that afternoon: “[W]e returned to the law firm to find dozens of potted plants. By the next day there were potted plants everywhere – in the lobby, in the corridors, and especially in Brendan’s office, which now resembled a terrarium.” I asked Sullivan if any of those plants are still around. They’re not he told me. But one lived 15 to 20 years and grew to the ceiling.

Incidentally, lost in the telling of the potted plant story is that in the 41 seconds before Sullivan uttered those famous words, he called for “fairness” – the mantra of his career -- six times in his objection to the Liman hypothetical.

While Sullivan was not in a court room when he distinguished himself from foliage, the line – with full credit to Sullivan -- has been used at least thirteen times by judges in opinions to make various points. See Celanese Chemicals Ltd. v. U.S., No. 04–00594, 2008 WL 5482052 (U.S. Ct. Int’l Trade Nov. 19, 2008) (“[T]he scope of judicial review is quite narrow. As the Court of Appeals has underscored, the Commission’s preliminary determination must be upheld unless it is ‘arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.’ On the other hand, the court is not a ‘potted plant.’”); U.S. v. Johnson, 42 M.J. 443 (U.S. Ct. App. Armed Forces 1995) (“As far as the implication that an issue not raised at the lower level cannot be raised before us, we are sure the court below would not sanction a ‘potted plant’ role for appellate counsel with regard to new issues.”).

In fact, in one decision, “potted plant” was not just a clever, but innocuous, expression used to make a point. Rather, the term took on a substantive role. See De Stasio v. Kocsis, A-5558-05T1, 2007 WL 1542607 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. May 30, 2007) (“We disagree with the hospital’s contention that the underscored comments of plaintiff, including the ‘potted plant’ reference, impermissibly invited the jury to conclude that the nurses had the authority to order a CBC test or to otherwise override Dr. Elkwood’s medical decision to proceed with the August 2000 surgery. Counsel’s remarks, using a well-known legal metaphor popularized in the Congressional investigation of Oliver North [footnote credits Sullivan], merely suggested that the nurses failed to perform their own duties in this case by presenting false information on plaintiff’s chart, and that the nurses had an important role to play in plaintiff’s overall care. We discern no manifest injustice in the circumstances, as the comments were within the bounds of fair advocacy.”)

Beat The Clock: Brendan V

In 1992, the Minneapolis band Beat the Clock recorded the song “Brendan V” on its Funk Bus album. I bought the C.D. It’s an interesting song. It describes Sullivan as the lawyer you call when all hope seems lost: “It doesn’t matter if you were the trigger man.” Or, how about, “What do you do when the files all say he was there that day? Find the guy who pulled them out and find the one mistake he made.” A line in the chorus: “You get the Brendan V. Sullivan, Jr.” is pretty catchy and I’ve had it stuck in my head a few times.

I couldn’t get off the phone with Sullivan without asking him what he thought of “Brendan V.” Had he ever met Beat the Clock? Sullivan had absolutely no idea what I was talking about. None whatsoever. He was completely dumbfounded. You gotta be kidding me?, I replied, incredulously. He wasn’t. “I never heard that before this moment,” Sullivan assured me. I’m not sure which of us was more in shock by what the other was saying.

Sure, Beat the Clock isn’t the Beatles. But still, how could Brendan Sullivan have spent the past 25 years not knowing that he was the subject of a song? After all, it’s right there in his Wikipedia entry. It must be because he has more pressing matters to attend to than sitting around Googling himself.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

Cross This Off One Comedian’s Bucket List

Meeting the legendary Jackie Mason backstage

at his Philly show in May. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Selfie Stick Injury: Insurer Writes Policy Covering Cell Phone Mishaps |

| |

Sometimes it seems as if there’s insurance for everything. Policies exist for a golfer making a hole-in-one, a wedding catastrophe and, so they say, Liberace’s hands were insured. When new bad things happen, or threaten, the insurance industry always seems to be right there with products designed to spread the risk. A few cases of Ebola not long ago -- boom, welcome Ebola insurance. Planes might fall out of the sky at midnight on January 1, 2000? Fear not. Here’s your Y2K policy. And as new technologies are developed, insurers respond with policies designed to protect against mishaps. Not long after drones began showing up under Christmas trees, drone insurance rained down. Pot is legal in some places. Many are doobie-ous that that can be done safely. The insurance industry rolled out marijuana policies.

So, on one hand, it comes as no surprise that an insurer is offering a policy designed to cover the risks of using a cell phone. But wait, cell phones have been around for a very long time you say. Nothing bad happens from using them. Who needs insurance? What’s the biggest risk of using a cell phone? Losing it? Dropping it?

Maybe that used to be the case – back in the day when cell phones had just one purpose. But as cell phones do more and more things, they are out of our possession for less and less time. Did you see that new app that makes really good guacamole? The more we use cell phones, the greater the risk of unintended consequences. Seeing an opportunity, enter CellRisk with its “Cellular Technology Legal Liability and First Party Policy.”

I got my hands on CellRisk’s policy form. It offers coverage for many types of risks associated with using a cell phone – a few of which I never even thought of. No doubt some of the coverages are likely available on existing policies, such as homeowners and health. But even if that’s the case, CellRisk touts in its promotional materials that its policy may offer higher limits than these others. Not to mention that, according to CellRisk, an insurer that issued a more traditional policy may balk at paying a claim with which it is unfamiliar.

Consider these coverage available from CellRisk under its Cellular Technology Legal Liability and First Party Policy:

Bodily Injury To Others Caused By a Selfie Stick. The insurer will defend and pay up to $250,000 for bodily injury to others caused by an insured’s use of a selfie stick. I guess those things can be dangerous. Think of it as “Put that thing down before you poke someone’s eye out” insurance.

Bodily Injury to the Insured While Taking a Selfie. It seems crazy, but the news is full of stories about people injured, even killed, while taking a selfie. The policy pays medical expenses up to $500,000, and a death benefit of $1,000,000 (less any medical expenses paid), if an insured is injured or killed while taking a picture of themselves (being injured or killed).

Humiliation. The insurer will pay $100,000 to an insured who, on account of inattention while staring at their cell phone, falls into a fountain or walks into a wall, and a video of it appears on the internet and goes viral. The policy contains a complex explanation of what it means to “go viral.” Rife for dispute I might add.

Bodily Injury to Others While Using a Cell Phone. The insurer will defend and pay up to $250,000 for bodily injury to others caused by an insured’s inattention while staring at their cell phone. No more worries about knocking over an elderly and infirm person while texting.

Quiet Car Injury. The insurer will pay up to $250,000 for injuries sustained by an insured, in an altercation, on account of the insured’s use of a cell phone on a train’s Quiet Car.

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

Congratulations Lauren Kelly: The Key To “Insurance Key Issues” 3d

|

|

|

|

| |

Jeff Stempel and I wrote the bulk of the 3rd edition of General Liability Insurance Coverage – Key Issues In Every State between the spring and fall of 2014. That summer I had the good-fortune to have help with my responsibilities.

Lauren Kelly, fresh off her first year at Villanova Law School, spent eight weeks as my Research Assistant. Day in and day out she did research to identify new coverage case law decided since the time of the second edition. Lauren also had the unenviable task of converting the gazillion Westlaw cites in the 2nd edition to Lexis form. [Lexis had acquired the electronic rights to the 3rd edition and part of the deal was that I’d make the citation changes.] Much about Lauren’s job was tedious – more than I could have handled. But she never complained (at least not to me) and did an amazing job.

Jeff and I were very pleased with how the 3rd edition of Insurance Key Issues turned out. Much credit for that goes to Lauren Kelly and her painstaking research and writing. Lauren’s days as a law student are now over. She graduated from Villanova on May 13. I can’t believe it. It seems like just yesterday that we were sitting in my office discussing new pollution exclusion decisions. Congratulations to Lauren on this wonderful accomplishment! |

|

|

|

| |

I’ve prepared Lauren well for the next phase in her legal career. After converting all of those Westlaw cites to Lexis, document review will seem exciting.

General Liability Insurance Coverage – Key Issues In Every State

See for yourself why so many find it useful to have, at their fingertips, a nearly 800-page book with just one single objective -- Providing the rule of law, clearly and in detail, in every state (and D.C.), on the liability coverage issues that matter most.

www.InsuranceKeyIssues.com

Get the 3rd edition here www.createspace.com/5242805 and use Discount Code NTP238LF for a 50% discount.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

Trump Puts “Most Important Liability Insurance Judge In America”

On His List Of Potential Supreme Court Picks

|

|

|

|

| |

As was widely-reported, on May 18 Donald Trump released a list of eleven judges who he would consider for the U.S. Supreme Court -- if presented with such task. The list included Justice Don Willett of the Supreme Court of Texas.

Justice Willett is well-known nationally as a grand master on Twitter. With over 49,000 followers he is easily the number one most popular tweeting judge. That’s a staggering number of followers for anyone, let alone a judge. Willett’s Twitter accomplishments include a formal recognition, by the Texas House of Representatives, as a “Tweeter Laureate,” for his “lively and engaging presence on Twitter.” [Willett is also a tremendously talented writer. I read his opinions even if they have nothing to do with insurance. And I usually read nothing that has nothing to do with insurance.]

Willett’s Twitter feed is one of only a handful that I never fail to read. There’s a reason why he has so many followers. His tweets are, well, just that good. I could try to explain why, but I’d do a bad job of it. To really appreciate Willett’s gift for this social media platform you need to go to @JusticeWillett and see for yourself. My personal favorites are the ones related to his enormous-Texas pride. Justice Willett has even tweeted a few things from Coverage Opinions, which is always very flattering. |

|

|

|

| |

I had the privilege of doing a Q&A with Justice Willett for the May 7, 2014 issue of Coverage Opinions. His Honor was very kind and generous with his responses. Check it out here http://coverageopinions.info/Vol3Issue8/Declarations.html. At that time Justice Willett was already widely-known for his Twitter presence – and had just 5,500 followers. [It’s simply amazing what happens when someone does a Q&A in Coverage Opinions. I just don’t get why people say that proximate cause is such a hard concept to grasp.]

Also in the May 7, 2014 issue of CO I did a separate story spilling 1,600 words why I believe that Justice Willett is the most important liability insurance judge in America. It was obviously a non-scientific conclusion, but I undertook a lot of analysis in reaching it. Check it out here. http://coverageopinions.info/Vol3Issue8/JusticeDonWillet.html

Of course, being the most important liability insurance judge in America is of no value on the U.S. Supreme Court. It’s like being the best figure skater in the Sahara. But imagine if it were. Would a candidate’s positon on the pollution exclusion be a litmus test for being confirmed? |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

David A. Gauntlett: Dean Of The “Coverage B” Bar

David Gauntlett, of Gauntlett & Associates in Irvine, California is the Dean of the “Coverage B” Bar. While no Blue Ribbon panel was convened to reach that conclusion, sometimes one isn’t needed. He just is. For over three decades, David has been litigating cases, for policyholders, involving coverage for intellectual property and various types of personal and advertising injuries. He has been lead counsel in such cases pending in over 30 states. When I see a Coverage B decision, the first thing I do is to check to see if David represented the policyholder. And so often he did. A Westlaw search: “personal or advertising w/5 injury and Gauntlett” returns an incredible 148 results. And some are precedent-setting.

The 1979 graduate of Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California at Berkeley, is a nationally recognized speaker and has been an adjunct professor at Boalt Hall, where he taught “Insurance Coverage for Intellectual Property, Antitrust and E Commerce.” David is also the author of numerous articles as well as the treatise “Insurance Coverage of Intellectual Property Assets.”

David was kind enough to answer four questions about his long time on the front lines of Coverage B. He touches on the history of coverage for intellectual property and various types of personal and advertising injuries, how he got started, some of his most significant cases and issues that he sees on the horizon.

1. The Obvious Question – What Led You in the Direction to Focus on Intellectual Property and Part B Coverage Cases?

It started with the 1976 ISO CGL policy, which included within its definition of the advertising injury offense “unfair competition” and “piracy.” That policy was drafted after the eight drafters took a Seaboard Surety policy, issued to advertising agencies, and added an exclusion for advertisers, broadcasters and publishers. Having accomplished that act, the eight drafters presumed that they had sufficiently limited its scope. None of the eight drafters were lawyers – none of them had any intellectual property litigation experience, or a sense of how those torts might interact with the policy they had drafted. It was sold for a 15 percent premium over cost.

Between 1986 and 2001, insurers made changes to policy language, substituting, adding or eliminating certain phrases relating to personal and advertising injury. As these changes were being made to Coverage B of the CGL policy over the years, I saw opportunities for coverage. A number of insurers, through a combination of redefinition and the inclusion of problematic phrases, sought to limit IP coverage. They have not, however, done so appropriately nor eviscerate the settled rule that a duty to defend one claim requires that the entire lawsuit be defended. Any significant reduction in coverage should be called to the insured’s attention. But that has not been true in this case. Such conduct runs afoul of state regulatory provisions such as that in New York Insurance Law section 3426(e).

For over a decade, few practicing had focused on the advertising coverage much less assessed its impact on intellectual property cases. Recall that until1984, when the Federal Circuit was created, there was very little high level litigation of IP torts by major law firms. Then, the Federal Circuit was created, and it became obvious that there was a value to patent litigation. Over time, IP firms grew from prosecution houses to litigation firms. Finally, they became absorbed into general practice firms, so the people with the expertise on the litigation end, which is where you need the expertise to think about the issue, became involved. Previously, IP firms had not focused on anything like the general business corporate situation, because they were boutique, specialty firms that did not have the expertise to deal with many other corporate issues. As for corporate counsel, they did not task personnel who dealt with IP litigation to investigate insurance, because it was not considered a big issue.

There has been a failure to combine the right practice elements. This is changing. Major law firms have coverage specialists; they also have antitrust and IP litigation groups, who now interact more. However, again, it remains interesting how disparate those elements are, and how few firms fuse those disciplines.

There isn’t a very large bar of policyholder attorneys who have the right background to litigate coverage issues for intellectual property cases, because you need to fuse those two disciplines. Most coverage attorneys have not litigated IP cases. IP attorneys may occasionally litigate a coverage case, but their coverage background tends to be isolated and, missing a few distinctions, they have often obtained disappointing results in litigation. Therefore, the results of policyholders have been uninspiring, given what the potential could have been, and still could be.

Certainly, the coverage results for patent claims has been disappointing; it is very difficult to procure under CGL policies. In trade secret misappropriation, there have been a couple of successful coverage cases, one from the Wisconsin Supreme Court, Fireman’s Fund Insurance Co. of Wisconsin v. Bradley Corp., 660 N.W.2d 666 (Wis. Sup. Ct. 2003), but often, it is because the court looks beyond the trade secret claim, and finds other elements of litigation that potentially implicate coverage.

The law in Wisconsin is the “four corners” rule, and the alleged taking of proprietary information was at issue. That was the core of the case, but one of the allegations also related to the taking of a design. The court said the allegations of the “taking of a design,” the misuse of the design, and the advertising based on the misuse of the design implicated coverage for “trade dress.” The court did not reach the issue of whether trade dress claims fell within the “misappropriation of style of doing business” coverage in the 1986 ISO form at issue, as there was separate coverage for trade dress as a form of trademark infringement coverage under the policy, which it found was broad enough to encompass trade dress.

This policy had a variant version of the 1986 ISO that included trademark infringement coverage – this happens on occasion. The court found there was a defense, and it did so by inferring that the misuse of the design would necessarily implicate a trade dress liability, even though trade dress, as a label for a count, had not been specifically pled. That is, by the way, how the law is supposed to work.

The Wisconsin Court of Appeal reversed, because it did not see that inference. Typically, whether a court finds a defense or not, is determined by how it views the inferences from the underlying allegations, as well as what law it applies. Obviously, if an insured has a better factual record from which to draw these inferences, by virtue of discovery that it propounded to the plaintiff, it has a better opportunity to argue the potentiality of coverage. Thus, it is always easier for the insured if the court considers facts beyond the pleadings.

2. What Are Your Most Satisfying Wins, in Terms of Difficulty of the Case, Dollars, Case Law Made and/or Whatever Other Criteria That You Use to Define Satisfying?

Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co. v. Watercloud Bed Co., Inc., No. SA CV 88-200 AHS, 1988 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 17572, 1988 WL 252578 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 17, 1988) (The first case nationally to find coverage for patent infringement lawsuit. The asserted claims could have involved advertising activity because the insured offered to sell infringing products triggering distinct liability for active inducement of patent infringement. The court found that there had not yet been an adjudication of willfulness so despite a prayer for such relief and or an award of treble damages a defense arose. Moreover, the insurer's motion for summary judgment on the duty to indemnify was not yet ripe.)

Union Ins. Co. v. Land & Sky, Inc., 247 Neb. 696, 529 N.W.2d 773 (Neb. 1995) (The first State Supreme Court to address coverage for patent infringement issues, concluded that the insured was entitled to a defense for claims of inducing patent infringement of a waterbed patent. Applying Nebraska law, it found that no public policy intruded to avoid coverage for claims of inducing patent infringement. It also found that piracy could encompass patent infringement and that a causal nexus could arise between claims of inducement and the insured’s advertising activities.)

Hewlett-Packard Co. v. CIGNA Property & Casualty Ins. Co., No. 99-20207 SW, 1999 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 20655 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 24, 1999) and Hewlett Packard Co. v. ACE Property & Casualty Co., No. C-99-20207 JW, 2003 WL 22126601 (N.D. Cal. March 4, 2003 and Hewlett Packard Co. v. ACE Property & Casualty Co., No. C-99-20207 JW, U.S.D.C. N.D. Cal. Nov. 23, 2003) motion for reconsideration denied. (Package inserts allegedly containing “fear, uncertainty and doubt” materials were advertisements. That the policy’s territory was broad enough to encompass claims filed in the U.S. so long as potential injury arose outside of the U.S. Extraterritorial advertisements of HP in the underlying action bore a causal relationship to false advertising claims against HP. False advertising as well as trade libel claims also fell within the policy’s coverage for the “advertising injury” offense of “unfair competition.” The court subsequently affirmed a special master award of over $50 million for defense fees and prejudgment interest to HP.)

Burgett, Inc. v. Am. Zurich Ins. Co., 830 F. Supp. 2d 953 (E.D. Cal. 2011) (Coverage for explicit disparagement was implicated by the false advertising claims in light of prior authority including E.piphany, Inc. v. St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co., 590 F. Supp. 2d 1244, 1252-1253, N.D. Cal., 2008 [litigated by G&A]. Because Burgett represented to Samick [claimant] it was the only holder of the SOHMER trademark, potential coverage for implied disparagement arose. The trademark exclusion was of no moment because “while the underlying complaint does not explicitly state a claim of disparagement, the Court finds that the complaint could be amended to state a claim for the same.”)

TRAX, LLC v. Cont’l Cas. Co., No. 10-CV-6901, 2012 WL 3777042, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 123141 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 29, 2012) (After a three-day trial, Gauntlett & Associates obtained judgment against Continental Casualty Company, a CNA company, in the aggregate sum of $2,152,587.60 in principal and prejudgment interest - the entire amount sought - against an insurer that had refused to settle a copyright infringement/trade secrets infringement case against its insureds. Applying Virginia law, which the Court had earlier ruled was applicable and which, the Court asserted, required the insureds to allocate their settlement payment, the Court found the insureds' $1.95 million settlement amount was 100% allocable to the covered copyright claim, with 0% allocable to the non-covered trade secrets claim. The Court also found no portion of the settlement sum was allocable to dismissed insolvent co-defendants, or to the value of a software license recited in the settlement agreement.)

Michael Taylor Designs, Inc. v. Travelers Property Cas. Co. of America, 495 F. App’x 830 (9th Cir. 2012) (Ninth Circuit affirmed ruling concluding that implicit disparagement arises despite absence of express allegations denigrating another’s products in false advertising dispute).

General Star Indem. Co. v. Driven Sports, Inc., 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7966 (E.D.N.Y. Jan. 23, 2015) (Judge Joseph F. Bianco predicted that the New York court of appeals would follow the emerging trend represented by decisions in diverse state Supreme Court decisions in Illinois, Texas, Pennsylvania, Washington and other earlier decisions in refusing to allow recoupment of defense fees paid even if no potential for coverage ever arose.)

Mkt. Lofts Cmty. Ass’n v. Nat’l Union Fire Ins. Co., 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 64014 (C.D. Cal. May 4, 2016) (Denying insurer’s motion for summary judgment based on findings that there was insufficient evidence to conclusively eliminate potential for coverage and a reasonable juror could find that the defendant failed to conduct an adequate investigation prior to denying coverage).

3. What Do See as Emerging Issues on the Intellectual Property and Part B Coverage Front (in addition to cyber)?

Lawyer/broker malpractice: Shaya B. Pac., LLC v. Wilson, Elser, Moskowitz, Edelman & Dicker, LLP, 38 A.D.3d 34 (N.Y. App. Div. 2006) (Legal malpractice arose where defense counsel failed to give notice to an excess insurer where it was evident that the demand for damages exceeded the commercial general liability policy limits. The defense counsel was insurer appointed counsel. The law firm retained by primary carrier to defendant’s insured in a pending action has an obligation to investigate whether the insured has excess coverage available. If so, it must file a timely notice of excess claim on the insured’s behalf. The appellate court reversed the trial court grant of a Motion to Dismiss.)

Patent plus: Concept Enters., Inc. v. Hartford Ins. Co. of the Midwest, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 6901 (C.D. Cal. May 22, 2001) (A duty to defend a trade dress infringement claim arose where it was asserted in conjunction with excluded claims causes of action for patent infringement, therefore implicating defense duties for the entire lawsuit. Hartford attempted to pay only 15% of the bills, based on its calculation of relative liability exposure for the covered trade dress re uncovered patent infringement claims. This approach was rejected by the court as inconsistent with the California Supreme Court’s Buss decision requiring an “immediate and complete defense” of all claims subject to right to reimbursement after performance. It concluded that any attempt to lessen the rate payable was unavailing under Civil Code § 2860 where less than all fees due were paid. The conduct constituted bad faith as a matter of law, entitling the insured to fees it incurred in its coverage dispute with Hartford.)

Trade secret plus: Jaco Envtl., Inc. v. Am. Int’l Specialty Lines Ins. Co., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51785 (W.D. Wash. May 19, 2009) (JACO moved for partial summary judgment on the question of whether its insurer, American International Specialty Lines Insurance Company (“AISLIC”), breached its contractual duty to defend JACO in a lawsuit brought by one of JACO’s competitors for claims including unfair competition and false advertising.)

Trademark plus: Spaulding Decon, LLC v. Federated National Ins. Co. fka AVIC, Case No. 14-CA-011618 (Florida Circuit Court, Hillsborough County, July 10, 2015) (A Motion to Dismiss was denied where fact allegations for covered unfair competition alleged liability beyond the excluded trademark infringement.)

Class action suits in false advertising cases: Basic Research, LLC v. Admiral Ins. Co., 2013 UT 6 (Utah 2013): The Utah Supreme Court admitted that the ISO policy language could cover “misuse” of an advertising idea “including deceitful advertising,” “where the underlying injury is directly caused by the deceitful advertising, regardless of the product’s failure to perform.” But then the court said that “in the instant case the ‘use’ of the slogan is not the wrongdoing … Rather they claim damages due to the allegedly false nature of those slogans and the resulting inducement to by a defective product.”)

Insurance Coverage To Facilitate Coverage For Antitrust/False Advertising Cases: Am. Inst. of Intradermal Cosmetics v. Soc’y of Permanent Cosmetic Professionals, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 160395 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 14, 2014) (permitting filing of a Third Amended Complaint in an antitrust lawsuit. The new pleading asserted fact allegations of disparagement nested within Sherman Act claims in order to facilitate securing insurance coverage benefits for the ongoing settlement negotiations with the defendant’s insurers. Judge Feess found it noteworthy that it was only upon the receipt of the specific insurance policies “that Plaintiff could assess, with retained insurance coverage counsel, how to proceed with additional claims that would trigger coverage.”)

4. What Other Areas of Insurance Coverage Have You Focused on and Activities Have You Pursued to Keep Your Perspective on Coverage Issues Fresh?

Each year, our firm reinvigorates its insurance practice, focusing on new coverage opportunities as well as pushing the envelope in coverage areas where we have traditionally focused on “personal and advertising CGL coverage and other forms of coverage for intellectual property disputes.

For example, our focus includes:

• Class action antitrust litigation

• Class action false advertising lawsuits

• Wage and hour class action lawsuits looking to CGL policies, Omissions, Employment Practices Liability, Employee Benefits Liability and Directors and Officers policies

We also focus on business solutions that use insurance assets. Hence, the title of my treatise, “Insurance Coverage of Intellectual Property Assets,” 2d Ed., © 2015, Wolters Kluwer. These include:

• Helping companies structure appropriate insurance coverage for

- intellectual property claims

- antitrust and class action false advertising exposure

- Wrap policies for complex construction projects

- Trust insurance for high value estates

- Directors and Officers/Errors and Omissions insurance for medical technology and other high-risk perceived areas of practice

• Assisting companies with corporate due diligence related to deal-making and:

- Negotiating representations in warranty insurance in connection with deal-making

- Reviewing portfolios of insurance in connection with proposed M&A activity to unearth buried treasure, i.e., insurance coverage opportunities that the parties may have not surmised that can create value for whichever party in a particular transaction could benefit from the availability of defense/settlement/indemnity reimbursement

We undertake expert witness/consulting work for: “Legal malpractice lawsuits” for failure to provide timely notice to insurers and Errors and Omissions disputes regarding the scope of coverage in various forms of malpractice claims. We also represent Plaintiffs in securing coverage benefits in antitrust, intellectual property, employment, and other disputes

Finally, we have expanded the frontiers of insurance coverage availability by focusing on new areas of coverage, for cyber liability exposure, helping to identify appropriate coverages, taking advantage of existing coverage where cyberspace claims arise, and looking to new frontiers of coverage based on risks which have little footprint in liability coverage analysis, such as nanotechnology claims, virtual reality, and the interface between international and domestic insurance programs in a range of contexts.

As one underwriter at Lloyds referred to our firm’s practice, we are their “quality control department.” As a sage commentator observed, “we secure insurance coverage where everyone knows that it does not exist.”

|

|

| |

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

Starbucks Sued For Too Much Ice In Its Drinks

|

|

|

|

| |

I love Diet-Coke. I drink more of it than I should. And my wife is on my back about it. And she’d be even more so if told her the real amount that I drink. I much prefer the soda from a fountain than a bottle. And that’s because of the added enjoyment that comes from the ice. Sloshing it around in the cup. Sucking on it. Chewing it. It’s as much a part of the drink as the drink. But ice in a fountain drink can be a tricky thing. You want it – but not too much. Of course, when the fountain is self-serve, I am able to obtain my ideal ice to soda ratio. But when someone else is filling the cup -- all I can do is watch and hope for the best.

Starbucks recently landed in hot water over ice in its beverages. On April 27 the coffee giant was sued in Illinois federal court in a putative nationwide class action. Lead plaintiff Stacy Pincus says that Starbucks advertises its cold drinks by the ounce. However, on account of ice in its beverages, customers who order and pay for a drink receive “much less than advertised – often nearly half as many fluid ounces.”

[As an aside, speaking of Starbucks beverages, I have always marveled at the company’s genius. It’s an impressive feat to get your customers to call a size small drink a “tall.” I’m small. I don’t call myself tall.]

Ms. Pincus describes Starbucks’s scheme this way in her complaint:

|

22. Starbucks’ drinks are created according to a standard designed practice. For Cold Drinks, the standard practice is to fill the cup to the top black line with the Cold Drink liquid. [There is a picture in the complaint depicting an empty plastic Starbucks cup with three horizontal lines.] Large pieces of ice are then added to the top of the cup. For example, if a customer orders a Venti iced coffee or shaken iced tea Cold Drink, the Starbucks employee will pour iced coffee or tea into the cup up to the top black line, as represented by this picture: [Here there is a picture in the complaint depicting a plastic Starbucks cup half-filled with a dark liquid.]

23. After pouring the Cold Drink in the cup, the Starbucks employee will add large pieces of ice to the top of the cup. Starbucks employees fill Cold Drink cups with ice using pre-measured plastic scoopers, which escalate in size depending on the size of the drink. For example, a Starbucks employee uses a larger scooper to add ice to a Venti drink than they would to add ice to a Grande drink. [Different size ice scoopers? Really? That doesn’t seem necessary. I have to check for that.]

26. The top black line on the Starbucks Venti Cold Drink cup typically represents approximately 14 fluid ounces, as demonstrated below. Put another way, when a Starbucks employee fills a Venti Cold Drink cup to the top black line, they are only pouring about 14 fluid ounces of Cold Drink into the cup, not 24 fluid ounces. (emphasis in original). [In case you aren’t getting this, there is a picture in the complaint of a Pyrex measuring cup filled with fourteen ounces of a dark liquid.]

|

Ms. Pincus, on behalf of herself and every person in America who has purchased a cold drink at Starbucks between April 27, 2006 and today – man that’s a lot of people -- seeks damages (including punitive) from Starbucks for such things as breach of express warranty, breach of implied warranty of merchantability, negligent misrepresentation, fraud and violation of various consumer protection statutes.

Stacy Pincus is right and nobody can dispute it – you don’t get 24 ounces of beverage when ordering a 24 ounce cold drink at Starbucks. Ice is part of the deal. But every beverage buyer knows this going in. It’s an unwritten clause in the unwritten beverage contract. Starbucks isn’t trying to fool anyone. If you don’t like it, ask for your drink without ice.

The case is Stacy Pincus, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated v. Starbucks Corporation, No. 16-4705, United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

I’ve Never Seen This Before:

Court Disallows Insured’s Personal Counsel: Could “Slant” Cases…Toward Coverage

|

|

|

|

| |

Courts have long been addressing whether an insured is entitled to independent counsel (i.e., not panel counsel), when its insurer is defending it under a reservation of rights. You know the drill. Insured says that the insurer must pay for independent counsel, since the complaint alleges both covered and uncovered claims, and if panel counsel is used he or she might “steer” the case toward a finding of liability for only the uncovered claims, since panel counsel wants to curry favor with the insurer, in hopes of receiving additional assignments. [I’m not sure how you actually “steer” a case in that way, especially without anyone noticing, but that’s neither here nor there.]

General Insurance Company of America v. Walter E. Campbell Co., No. 12-3307 (D. Md. May 12, 2016) offers the opposite version of this tale. Here the insured was not permitted to use personal counsel because he or she might steer the case -- toward covered claims. I’ve never seen this scenario before. That’s not to say the issue has never arisen. But, if it has, it’s eluded me.

Campbell involves coverage for asbestos bodily injuries. As is so often the case, it has been the subject of lengthy litigation and oodles of coverage issues. The one at hand came about because there was a settlement between Campbell and certain insurers. This resulted in two classes of insurers – Settled Insurers and Non-Settled Insurers.

On account of the settlement, Campbell was now required to participate in defense and indemnity to the same extent as Settled Insurers. But here’s the rub – only so-called “operations” claims were potentially covered under the Non-Settled Insurers policies. [The Non-Settled Insurers disclaimed coverage for “products and completed operations” claims.] At issue was how to handle the defense, between Campbell and the Non-Settled Insurers, of the “operations” claims.

The court concluded that, with Campbell having the largest share of the defense of the operations claims, it was appropriate for Campbell to take the lead in the defense – with certain qualifications.

Campbell unilaterally replaced its long-standing defense counsel, Flax and Spinelli, with the law firm of Morgan Lewis in over 570 pending asbestos suits. However, of note, Morgan Lewis was also representing Campbell in the coverage dispute. The Non-Settled Insurers viewed Morgan’s role, of both defense counsel and coverage counsel, as a clear conflict of interest. The Non-Settled Insurers advocated for the retention of Dehay & Elliston, a law firm with considerable experience defending asbestos cases in Baltimore where most of the cases are pending.

Now, back to those qualifications governing Campbell’s defense, here’s the money paragraph: “One of those qualifications is that [Campbell] cannot continue to retain conflicted counsel to defend these suits and, as long as it does so, Non-Settled Insurers shall have no defense or indemnity obligations with respect to those suits in which Morgan Lewis remains defense counsel. Given the long and protracted efforts of Morgan Lewis to pull cases into coverage under the Non-Settled Insurers’ policies, Morgan Lewis cannot also be placed into the position where it can slant the defense in a manner that could render the claims covered claims.” (emphasis added).

What’s good for the goose…

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

Homer Simpson Moment: D’oh -- $30 Million -- What Could Have Been

|

|

|

|

| |

I can’t help but think that PNC Financial had a Homer Simpson “D’oh moment” at some point during the litigation in PNC Financial Services Group v. Houston Casualty Company, No. 15-1656 (3rd Cir. May 2, 2016). At issue before the Third Circuit was coverage for $102 million in settlements – Wow! -- of suits involving the manner in which PNC processed debit card and ATM transactions in order to maximize fees for overdrafts. Of particular interest here, the settlements included $30 million for plaintiff’s attorney’s fees. The court held that it was not covered. But could that outcome easily have been different?

Policies issued by two insurers provided coverage for “all Loss for which the Insured becomes legally obligated to pay on account of any Claim first made against the Insured.” “Loss” was defined as “Claims Expenses and Damages.” “Damages” was defined as “a judgment, award, surcharge or settlement ... and any award of pre- and post-judgment interest, attorneys’ fees and costs.”

However, the policies contained exceptions to the definition of “Damages,” including one for “fees, commissions or charges for Professional Services paid or payable to an Insured.” This was referred to as the Professional Services Charge Exception. For various reasons, not important here, the Third Circuit held that the Professional Services Charge Exception applied to preclude coverage for losses that constitute fees or charges. In reaching this conclusion, the federal appeals court affirmed the decision of the District Court.

However, the Third Circuit disagreed with one aspect of the District Court’s decision. The District Court had held that the approximately $30 million awarded to class counsel, as attorneys’ fees and costs, did not fall within the Professional Services Charge Exception. Rather, to the District Court, the amount awarded to class counsel for attorneys’ fees and costs fell within the definition of Damages, which included an “award of ... attorneys’ fees and costs.” Hence, this approximately $30 million represented PNC’s payment of class counsels’ attorneys’ fees and not a refund of fees or charges for Professional Services. Therefore, the District Court held that this amount did not fall within the Professional Services Charge Exception.

However, the appeals court did not see it this way: “PNC did not agree to pay a specific sum to settle the claims related to overdraft fees and additionally pay the attorneys’ fees ultimately awarded to class counsel. Instead, PNC and the class plaintiffs agreed that PNC would pay a lump sum to the class in order to settle their claims and that PNC would have no further obligation once it paid the lump sum. That some money from each common fund was subsequently paid to counsel upon order of the respective courts does not change the purpose of the funds—to resolve the class members’ claims for wrongly collected overdraft fees. Notably, the settlement agreements expressly provided that PNC’s obligation remained the same regardless of how much in attorneys’ fees, if any, the District Courts eventually awarded. Once the District Courts decided to award counsel fees, the parties agreed that the awarded fees and costs would be paid by ‘the plaintiff class as a whole rather than the defendant.’”

In other words, the Third Circuit explained: “[T]he approximately $30 million awarded to class counsel as attorneys’ fees and costs do not constitute an award of attorneys’ fee and costs that PNC was legally obligated to pay. Rather, PNC was legally obligated to pay $102 million to reimburse class members for charged overdraft fees, from which the class plaintiffs—not PNC—paid their attorneys approximately $30 million for their services. Accordingly, the entire $102 million in settlement payments constitutes a refund of fees or charges for Professional Services that class members paid to PNC and National City Bank, and as such, are excluded from coverage pursuant to the Professional Services Charge Exception.”

The implication of the Third Circuit’s decision seems to be that, if the $30 million in attorney’s fees had been structured differently in the settlement, i.e., characterized as a separate obligation of PNC, in addition to the amount that it was obligated to pay for reimbursement of overdraft fees, then such attorney’s fees may have been amounts that PNC was legally obligated to pay and outside the scope of the Professional Services Charge Exception. D’oh!

[If this had been the case, then the insurers may have argued that, if no coverage were owed for reimbursement of overdraft fees, then no coverage should be owed for plaintiff’s attorneys fees incurred to achieve a settlement of such uncovered overdraft fees. But that’s neither here nor there in light of the decision reached.]

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

U.S. Supreme Court – Yes SCOTUS – Asked To Hear A Bad Faith Failure To Settle Case

|

|

|

|

| |

Chance of the United States Supreme Court accepting certiorari in a liability coverage case – 1,000,000:1. Chance of Randy Maniloff beating Steph Curry in a three-point shooting contest: 999,999:1.

Yes, the odds of the U.S. Supreme Court accepting cert. in a liability coverage case really are that long. So, needless to say, it was a real shocker when I saw that a policyholder in a bad faith failure to settle case asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review an adverse result from the Fifth Circuit. And, of course, it was not a surprise when the U.S. high court R.S.V.P.ed no. Of course not. My cousin Vinny could have beat back this cert. petition.

So just what was it that caused a policyholder to throw the longest Hail Mary in the history of insurance jurisprudence?

At issue in Hemphill v. State Farm, 805 F.3d 535 (5th Cir. 2015) was coverage for a catastrophic injury in an automobile accident. The driver of the not-at-fault vehicle – Rodney Taylor -- was rendered a paraplegic. The driver of the at-fault vehicle was Patrick Hemphill. State Farm insured Hemphill’s father’s automobile. The policy provided a $50,000 per person limit. Heather Taylor was also injured. [The situation started out poorly for Hemphill. He initially said that he was not the driver, but his girlfriend was, since he had a suspended license. He also initially denied running the stop sign, but then admitted that he did.]

Following several offers, State Farm ultimately came up to offering the Taylors $50,000 each. The Taylors declined and the case went to trial. A jury returned a verdict in Mr. Taylor’s favor for just under $3,000,000. State Farm paid the $50,000 policy limit to Mr. Taylor in partial satisfaction of the judgment.

Mr. Hemphill filed suit against State Farm in Mississippi District Court, alleging that the insurer breached its fiduciary duty which led to the excess verdict. The District Court found for State Farm and the matter went to the Fifth Circuit.

The Fifth Circuit made clear that “when a suit covered by a liability insurance policy is for a sum in excess of the policy limits, and an offer of settlement is made within the policy limits, the insurer has a fiduciary duty to look after the insured’s interest at least to the same extent as its own, and also to make a knowledgeable, honest, and intelligent evaluation of the claim commensurate with its ability to do so. If the carrier fails to do this, then it is liable to the insured for all damages occasioned thereby.”

Pivoting from this general rule, the Fifth Circuit described the issues before it this way: “Here, it is undisputed the Taylors did not make a settlement offer. Hemphill contends that notwithstanding the Taylors’ failure to make a settlement offer, State Farm breached the following two duties: (i) to timely offer to settle the claim because the claim amount greatly exceeded the policy limits, and (ii) to timely disclose the policy limits to the Taylors. We address, in turn, whether an insurer owes these two duties to its insured absent a settlement offer within the policy limits by a third-party claimant.”

Specifically, State Farm made a settlement offer to Mr. Taylor “five and a half months after State Farm received notice of Hemphill’s admission that he ran the stop sign, two months after State Farm received all of Mr. Taylor’s medical bills, and two days after Mr. Taylor filed the Underlying Lawsuit. Hemphill contends State Farm had a duty to make this settlement offer earlier because State Farm knew Mr. Taylor’s claim amount greatly exceeded the policy limits.”

The appeals court disposed of the “failure to make an offer” issue quickly. Hemphill pointed to a statement by the Mississippi Supreme Court in a 1983 opinion which said that “there is authority for the proposition that in dangerous cases it is the duty of the insurance carrier to initiate settlement offers on its own.” The Fifth Circuit, however, dismissed this as “just dictum,” and noted that no Mississippi court since it had discussed this dictum or cited to the non-binding cases that the 1983 case cited. Held: “Indeed, over the thirty-three years since Hartford [1983 case], no case from either the Mississippi Supreme Court or a Mississippi intermediate appellate court has suggested or even hinted that the Mississippi Supreme Court would hold that an insurer has a duty to make a settlement offer absent a settlement offer by the claimant.”

As for an insurer’s duty to disclose policy limits, the Court held that “there is no genuine dispute that State Farm verbally disclosed the policy limits to the Taylors before Mr. Taylor filed the Underlying Lawsuit. Having verbally disclosed the policy limits, State Farm did not have an additional duty to disclose the policy limits in writing via a certificate of coverage before Mr. Taylor filed the Underlying Lawsuit.”

The most interesting part of the case – to me at least – is that State Farm admitted that it did not advise Hemphill of his potential excess exposure and right to retain independent counsel. However, as the Fifth Circuit saw it, there was a causation problem for Hemphill, holding that there was no genuine dispute that, “before Mr. Taylor filed the Underlying Lawsuit, Hemphill was aware of his potential excess exposure and consulted an independent attorney for financial protection. Thus, Hemphill independently knew the information that he complains State Farm did not advise him about. For these reasons, the district court did not err in finding no genuine dispute that the excess judgment was not caused by State Farm's failure to advise Hemphill of his potential excess exposure and right to retain independent counsel.”

Mr. Hemphill Goes to Washington

Obviously this is a serious case – for Mr. Hemphill, facing a huge judgment and Mr. Taylor, facing a catastrophic injury and virtually no recompense from the driver who caused it. Under these circumstances, Hemphill, presumably, must have believed that, despite the very, very long odds, he had no choice but to file a Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court.

It is beyond the scope here to write chapter and verse on the competing cert. petitions. Instead I’ll set out a portion of State Farm’s petition that discussed why the Supreme Court should decline to accept the matter for review. State Farm’s Petition stated:

“This case meets none of this Court’s criteria for granting certiorari. There is no conflict as to any question of federal law between the Circuit Courts, between the Fifth Circuit and a state high court, or between the Fifth Circuit and any decision of this Court. Nor has the Fifth Circuit departed from the usual practice and course of proceedings so as to justify the exercise of this Court’s supervisory power. As this Court had made clear, certification is not ‘obligatory’ even if available, and the decision whether to certify or abstain ‘rests in the sound discretion of the federal court.’ Lehman Bros. v. Schein, 416 U.S. 386, 391 (1974). Here, the Fifth Circuit acted well within the bounds of its discretion in declining to certify to the Mississippi Supreme Court the question suggested by Petitioner.

Moreover, this case does not present the federalism and other concerns that, under this Court’s jurisprudence, counsel the federal courts to defer to the state court on an issue of state law. The Fifth Circuit has not invalidated a state law on federal constitutional grounds and has not ventured into legal territory where it is an ‘outsider.’ Furthermore, Petitioner chose a federal forum for this diversity case and should not now be heard to complain that the federal courts should not have decided the issues of state law that his claims presented. Granting certiorari in this case will only result in delay and obstruction in the functioning of the federal courts in diversity cases.

Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit’s decision in this case presents no issue of federal law requiring resolution by this Court and satisfies none of this Court’s criteria for granting certiorari. See Sup. Ct. R. 10.”

This is no doubt the reason why unsuccessful litigants in coverage cases – policyholders and insurers – virtually never, ever seek SCOTUS review.

So what made Hemphill take his shot? Certainly not an argument that the case somehow, some way, had a federal or constitutional hook. The petition for review stated:

“Insurance companies demand documentation (written documentation) before they will pay out a single solitary penny in settlement of claims. Under the facts of this case, or in any serious claim, it is submitted that a third party claimant such as Taylor is not going to accept oral representations of an insurance agent over the phone, and the State Farm adjuster plainly knew this and acknowledged this. State Farm is a company that understood that it did not expect Taylor to settle his claim without delivery of the certificate of coverage.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals decided this case on an issue not addressed under Mississippi law that neither party raised in the pleadings, at the summary judgment level or at the appellate level. Mississippi has a well-established protocol in place to answer such questions. The Fifth Circuit has utilized that procedure sparingly. But here, rather than certify that question to the Mississippi Supreme Court and receive a definitive answer, the Fifth Circuit made a sua sponte ‘Erie guess’ that deprived Patrick Hemphill of his right to have a jury decide his case. It is submitted that the industry standard is to provide that certificate of coverage when requested particularly so when the claimant had been so severely injured, and the coverage is inadequate to avoid financial disaster to an insured like Hemphill.”

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 6

May 31, 2016

Judicial Disqualification: Crazy Facts In A Coverage Case

|

|

|

|

| |

The facts at issue in Draggin’ Y Cattle Company v. Addink, No. DA15-0354 (Mont. May 3, 2016) are really bizarre. And the chances of them being repeated are about one in -- never. But, even so, I couldn’t help myself and selected it for CO.

The story, with some steps omitted because not relevant here, goes like this. In January 2011, Peters filed a complaint against Junkermier, alleging multiple counts stemming from tax services Junkermier performed for Peters. Junkermier tendered his defense to New York Marine under a professional liability policy. New York Marine undertook Junkermier’s defense under a reservation of rights. In December 2013, following some litigation between Peters and Junkermier, concerning statute of limitations, a Judge Huss assumed jurisdiction of the case. In November 2014, Peters and Junkermier entered into a settlement agreement --10 million bucks -- and stipulation for entry of judgment without New York Marine’s participation. The District Court issued an order scheduling a hearing on the stipulated settlement’s reasonableness.

[If the hows and whys of a $10 million settlement, by a party being defended under a ROR, and without its insurer’s participation, was an issue, it was not discussed in the opinion.]

Getting back to our story… New York Marine filed a motion to intervene in the reasonableness hearing. It was granted. In March 2015, the trial court entered findings of fact, conclusions of law and an order finding that the stipulated settlement amount of $10,000,000 was reasonable. Junkermier was not liable for the stipulated settlement.

New York Marine then asserted -- for the first time -- that Judge Huss erred by not disclosing an apparent conflict of interest. “New York Marine claims that the alleged conflict stems from a complaint that a former court reporter filed against Judge Huss in February 2014. In October 2014—during the pendency of this case—Judge Huss individually entered into a stipulation and confession of judgment. The Office of the Court Administrator (OCA) had been paying for Judge Huss’s defense and Judge Huss allegedly entered into the stipulated settlement without the OCA’s participation or knowledge. On November 17, 2014—four days after Peters and Junkermier entered into their stipulated settlement—the OCA filed a complaint against Judge Huss in a Helena district court seeking a declaration that it had no duty to defend or indemnify him. In its complaint, the OCA specifically contested the stipulated settlement amount’s reasonableness. Judge Huss did not disclose the stipulated settlement or his dispute with the OCA to the parties in the case at issue. Judge Huss resigned effective January 1, 2016.”

OK, let’s review this -- New York Marine is fighting the reasonableness of a settlement entered into by an insured without consent. And the judge hearing that case, and who decided that New York Marine’s insured’s $10,000,000 non-consent settlement was reasonable, was, himself, at the same time, arguing that his own settlement, undertaken without his insurer’s consent, was reasonable. Do you know why this is all true? Because you couldn’t make it up.

New York Marine’s argument went like this: “Judge Huss’s potential conflict of interest raises reasonable questions regarding his impartiality. New York Marine contends that the ‘undeniable parallels between Judge Huss’ interests in the litigation he was (and still is) defending in his personal capacity and [Peters’s] interests in not permitting [New York Marine] to meaningfully challenge the stipulated settlement’ create ‘an apparent and significant conflict of interest.’ As such, New York Marine claims that Judge Huss was required, at a minimum, to disclose his apparent conflict of interest to the parties under the Montana Code of Judicial Conduct.”

After concluding that New York Marine had the right to raise the disqualification issue for the first time on appeal, the Montana Supreme Court turned to whether Judge Huss should have disclosed his own situation to the parties.

The court was not persuaded by Peters’s argument against disqualification – that it would be like requiring disqualification, from a car accident case, of every judge who had himself ever been involved a car accident. The court saw it differently: “A judge’s average personal experiences—including being involved in a car accident—undoubtedly shape the judge’s perspective. This does not mean, however, that such experiences necessarily preclude a judge from maintaining an ‘open mind in considering issues that may come before a judge.’ . . . As such, a judge’s average personal experiences do not generally lead to reasonable questions about the judge’s impartiality and subsequent disqualification under Rule 2.12.”