|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6 - Issue 9

December 13, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jeh Johnson’s long frame sits in a soft leather arm chair in his office. But despite how comfortable he looks, the former Secretary of Homeland Security is never in it for very long. He is constantly jumping up to show me something of interest on a wall or shelf or to retrieve something from a drawer. Or to grab my suit jacket, folded sloppily on his sofa, and kindly place it on the back of a chair.

Johnson and I are high above Sixth Avenue, in Mid-town Manhattan, in the seating area of his corner office at powerhouse Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. That Johnson has an office at Paul Weiss was no easy feat. The firm turned him down for a job during his third year of law school. “I didn’t even get a call back,” he told me. “I still have the rejection letter.”

And it is not just a career at Paul Weiss that seemed unlikely at one time. Just graduating from college was no sure thing. At the end of his first year at Morehouse College Johnson was staring at a 1.8 grade point average.

But some things happened during Johnson’s Sophomore year that changed his trajectory. Now instead of frequent visits to the dean’s office, he was on a path that would one day send him on regular trips to the Oval Office.

The long-time Paul Weiss attorney, and member of President Obama’s Cabinet, was kind enough to let me visit him to reflect on his diverse career in private practice and public service and homeland security. For well over an hour, Johnson, warm, engaging and telling me not to worry that we’re going over the allotted time, told stories that left me speechless and gave very thoughtful answers to my questions. No, Secretary of Homeland Security is not the most thankless job in America he told me. Is a cyber 9/11 coming? He thinks it may already have. What’s it like to give the order to kill someone? Few can describe that. Johnson can. And yes, the man responsible for TSA took off his shoes when going through airport security. You bet I asked. |

| |

The Morehouse Spirit of ‘76

Jeh Johnson, 60, entered Morehouse College in 1975. A poor start seems unexpected from the grandson of a distinguished sociologist and president of Fisk University and son of an architect, Columbia graduate and Vassar College professor. Johnson’s great-grandfather also provided large shoes to fill. An emancipated slave, who taught himself how to read and write, he graduated from college and went on to become a Baptist minister.

Johnson said he was a decent student as a youngster, but that deteriorated. High school was a world of Cs and Ds. “A C was a gift,” he said. “I just didn’t think it was part of my persona to be a good student.”

Poor grades continued when Johnson first arrived at the all-male, all-black college in Atlanta – with Spike Lee and Martin Luther King III as classmates. But the tide turned after his first year. “I went there,” Johnson said, “and discovered other young black men who were very motivated, very dedicated and very studious. That was new to me. The spirit at Morehouse was contagious. It was impossible not to be infected with it after a year or so. So my first year I had a 1.8 GPA. By Sophomore year, when I’d given up football, baseball, track and everything else, except studying, that’s when I took off and I discovered that I had a brain.”

Home from college in December 1976, Johnson’s father suggested that he read an article in The New York Times – “The Law Firm That Stars in Court.” The story was a profile of Paul Weiss, describing the firm’s celebrity clients and notable lawyers, as well as its financial success. “Senior partners,” the article declared, “whose time is billed at $250 an hour and more, might easily take in $200,000 a year.”

Johnson walked across his office and grabbed a copy of the Times article from a drawer. He read me one particular passage: “On many levels – the celebrity of its clients, the high proportion of government officials and agencies it has represented and the frequency with which its partners move in and out of government service – Paul, Weiss is as close as any New York City law firm to the public consciousness.” “First impressions are powerful things,” Johnson told me.

Johnson left Morehouse, entered Columbia Law School and decided that the big firm life was right for him. He landed at Sullivan & Cromwell. But the firm wasn’t what he was looking for. So after a year and a half he tried again at Paul Weiss. This time the outcome was different. “Right away the place felt right for me,” Johnson said. But despite how satisfied he was at the firm, he also knew he wanted to go into public service, or maybe elected office, at some point. Having worked on Capitol Hill during college summers, and volunteered for the Carter campaign in 1976, he had been bitten by the bug.

And Johnson did as planned – leaving his high-powered litigation practice at Paul Weiss four times -- serving as an Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, General Counsel of the Air Force and General Counsel of the Defense Department, where he oversaw 10,000 lawyers and co-wrote the report that paved the way for the repeal of “Don’t Ask. Don’t Tell.” In late 2013, the man born on September 11th was sworn in as head of Homeland Security. I bring up that New York Times article, which commented on the frequency with which Paul, Weiss partners move in and out of government service. “It was pre-ordained,” Johnson replied.

But these several leaves of absence from Paul Weiss are not, Johnson assured me, a matter of “hey I’m getting bored. I want to try other things.” “I believe in service to the country,” he told me, “as well as excellence in the practice of law.”

Johnson’s resume – combining long-time loyalty to the same law firm with several stints in public service -- is certainly unique. So is where he keeps it -- in his drawer. Literally. Johnson stood, walked over to his desk and signaled for me to join him. He pulled opened the top drawer. The bottom was covered with writing in a thick marker. It was a list, Johnson explained, of all of the places where his desk has lived since he acquired it in 1994. He takes me through the entries. It is Wikipedia on a tree: “Paul Weiss, 1994 to 1998. It was home in my attic in Montclair [New Jersey]. I brought it to the Pentagon in 1999 to January ‘01 at the end of the Clinton administration. Back to Paul Weiss for eight years. . . . Then when I went to the Pentagon with Obama in ‘09 to the end of the first term. Then he drafted me to be Secretary of DHS so I brought it to DHS. And it arrived back here December 20, 2016.” |

| |

“They’re Waiting For You To Tell them It’s Okay To Kill Him.”

Johnson is the nation’s fourth Secretary of Homeland Security. The first three were also lawyers. I told Johnson that this seems like a bad idea. After all, being DHS Secretary obviously requires making quick decisions at times. Lawyers, on the other hand, are frequently not in the quick-decision business. They analyze, research, get six peoples’ advice, have 30 days to do this and 60 to do that.

Johnson understood my point – and acknowledged that law school, with its focus on issue spotting, does not teach decision making – but he did not agree with my conclusion. There is a “decision making spectrum,” he explained, “between those who make flash judgments, based on just a little bit of information” and “someone who doesn’t want to make a decision and keeps asking for more information.”

Johnson’s decision making style as DHS Secretary, he told me, was somewhere in the middle: “I want to make sure I’ve heard from all of the stakeholders. I want to make sure I’ve heard from all of the component leadership within the department who will be affected by this decision and who will know how to implement it. . . . Bob Gates taught me if people feel like they’ve been heard, and listened to, they may not agree with the decision, but they’ll likely support it.” “There are definitely some lawyers, in non-lawyer, executive positions, who are guilty of what you said,” Johnson concedes, “but there are others who are prepared to make up their minds pretty quickly.”

On the subject of decision making, there may be none more challenging, for any lawyer, than what Johnson experienced in one aspect of his job as General Counsel of the Defense Department: signing-off on drone strikes and other counter-terrorism operations. About a month into it, Johnson explained, he was visited by some special operations personnel from the Pentagon. After they presented the case for taking out a terrorist, Johnson’s deputy looked at him and said: “They’re waiting for you to tell them it’s okay to kill him.” Johnson’s first reaction: “I’m not God.” Johnson told me that he frequently had to give such legal sign-offs, following his review of information from various sources. “That was probably the most serious aspect of my job,” he said. “And I took it very seriously.” He also made it his business, when possible, to watch the video of every drone strike he authorized so he could “see the gravity” of his actions.

Johnson told me that, “without a doubt,” helping to develop and refine the legal architecture, for the counter-terrorism efforts in the Obama Administration, was “the most intellectually stimulating part of my legal career.” [The New York Times reported in 2015 the Johnson was one of four government lawyers who worked in intense secrecy – without the knowledge of aides or even the Attorney General – to develop the rationales to overcome any legal obstacles surrounding the impending raid to capture Osama bin Laden.]

Johnson’s career being “pre-ordained” in a 1976 New York Times article is not the only eerie foreshadowing that he has experienced. In 1992, as a Paul Weiss associate, Johnson, with some assistance, represented a New York City police officer, pro bono, accused of homicide for throwing a child off a rooftop. The grand jury returned a verdict of no true bill. The allegations against the police officer were later completely discredited. Nine years later the officer was at the World Trade Center on September 11th and saved lives -- and almost lost his own. Today that former New York City detective, Roger Parrino, Sr., after serving as Senior Counselor to Johnson at DHS, is the Commissioner of Homeland Security for the State of New York.

Johnson and Parrino remain close. They were recently together at the site of the killings on a bike path in New York City near the West Side Highway. Johnson grabbed his phone to show me some pictures of it. On the subject of that attack, Johnson told me that, regrettably, he was not surprised by it. |

| |

|

| |

Secretary of DHS: The Most Thankless Job In America?

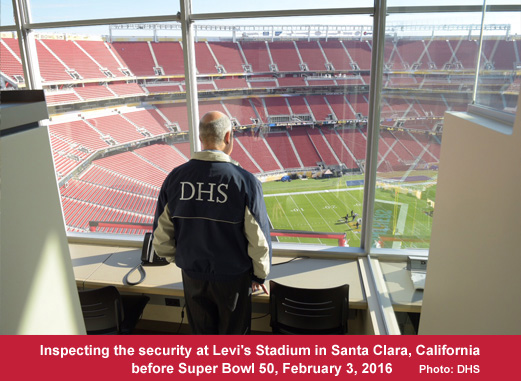

Homeland Security is the third largest Cabinet department. Johnson managed 230,000 employees, in 22 different components and agencies, including U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Transportation Security Administration, the Coast Guard, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Secret Service.

Despite its enormous size, and wide set of missions, Johnson told me that DHS is not too big, when I suggested otherwise. “There is virtue,” he explained, “in having within the purview of one Cabinet-level Secretary, the responsibility for all of the different ways that you can get into this country – in cyberspace, air, land, sea.”

Secretary of Homeland Security, I told Johnson, seems like the most thankless job in America. You work hard to prevent terrorist attacks. But much of that is done in secret so you get no credit for saving lives. Then, someone’s Chihuahua gets patted down at LaGuardia and you have to listen to late night comics make jokes about TSA. There must have been days where you said to yourself – why can’t I be Secretary of Agriculture? Johnson chuckled.

Johnson acknowledged that in DHS “you are always on the defensive team. You are never on the offensive team, where you can hold a press conference because you brought an indictment or you got a conviction. . . . A lot of times the press doesn’t find defense to be very sexy or interesting.”

And it’s true, he said, “there are a lot of plots that are interdicted, interrupted, at very early stages that the public never hears about and the press doesn’t write about.” But, “having said that,” he continued, “a lot of people did say to me ‘thank you for your service. Thank you for keeping us safe.’”

While Johnson doesn’t see DHS Secretary as a thankless job, he acknowledged the unavoidable truth: “In the world of homeland security, one thousand successes equals one failure. . . . If you don’t bat a thousand, but bat .999, you are going to get blamed. . . . Some days I felt like my job was to catch rain drops.”

Johnson didn’t even take the one seeming perk of the job – not having to remove his shoes when going though airport security. At certain times he was not permitted to fly commercial. But when he did he insisted on removing his shoes when going through the TSA checkpoint. Johnson even pulled an “undercover boss.” He grabbed his phone to show me a picture of himself, in full TSA uniform, assisting an elderly passenger. He went unnoticed the day he worked as a TSA agent.

Is A Cyber 9/11 Coming?

I asked Johnson if he sees a cyber-terrorism event coming, of such magnitude, that it will forever change how the subject is viewed. In other words, will we experience a “cyber 9/11?” To my surprise, he thinks we already have. “I hope last year’s election was that. That’s my hope. That what happened, and I think this is true, to a very large extent, raises peoples’ awareness and consciousness of the capabilities of bad cyber actors and what the can do. Leon Panetta said there was going to be a cyber Pearl Harbor. The 2016 election may have been it.”

|

| |

|

| |

The Last Stop For The Desk

Given Johnson’s prior leaves of absence from Paul Weiss, to pursue his commitment to public service, my last question was the obvious one – will another entry be made inside his desk drawer? His answer is clear and unambiguous, in both words and tone - no. “I had ten really remarkable years with Barack Obama. And now I’m content to be done.”

Johnson is also pleased to be rid of the Secret Service. He praised their work, but told me he is happy to now be able to drive his own car, take the bus and subway and go to the bathroom in a public place without the need for an operational plan.

Johnson told me that he knows that the net worth of some of his partners is multiples of his. But he has no regrets about his public service work, calling it “the most gratifying part of my career.” “Having gay service members introduce me to their spouses and saying ‘thank you for what you did,’ you don’t get those experiences in private life.”

At the end of our meeting Johnson walked me to the elevator. How am I getting to Penn Station, for the train back to Philadelphia, he wanted to know. My plan had been a cab. But it was now pouring. So I knew I was headed for the subway. Hearing this, Johnson jumped into action: Take the 51st Street exit. Go down to Seventh Avenue and there’s a subway at 50th Street. Take the number 1 train downtown. It’s the second stop. The mission was a success. The federal government took Jeh Johnson out of New York a few times. But nothing will take New York out of Jeh Johnson. |

| |

[Elizabeth Vandenberg, 1L, University of Iowa College of Law, assisted with this article] |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

The Organic and Green Version Of The Commercial General Liability Policy

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

There sure are a lot of strange organic foods out there these days. You can get organic tortilla chips, organic mustard and, get this, organic Capri Sun juice boxes. But organic officially jumped the shark when I saw organic Swedish fish on the counter of my local coffee shop. You gotta be kidding me. Even healthy Swedish people don’t eat organic Swedish fish.

With so many organic foods for sale, as well as all the efforts underway to go green, it seems only a matter of time before ISO introduces an organic and green version of its commercial general liability form. Those guys are always coming up with insurance products to keep pace with society’s comings and goings.

Here are ten ideas for ISO to consider for its new healthy and environmentally friendly CGL policy:

Mold Exclusion is eliminated. After all, living organisms should be cherished.

The Auto Exclusion now contains an exception for electric cars. Except Teslas. Those people can afford auto insurance.

The Voluntary Payments provision has been amended and now reads as follows: “No insured will, except at that insured’s own cost, voluntarily make a payment, assume any obligation, or incur any expense, other than for first aid or to save a whale.”

The Pollution Exclusion now contains an exception for manure as it’s useful as fertilizer. Take that Wilson Mut. Ins. Co. v. Falk, 857 N.W.2d 156 (Wis. 2014) and Wakefield Pork, Inc. v. RAM Mut. Ins. Co., 731 N.W.2d 154 (Minn. Ct. App. 2007) and Dolsen Cos. v. Bedivere Ins. Co., No. 16-3141, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 151057 (E.D. Wash. Sept. 11, 2017).

The “Your Work” Exclusion does not apply to an insured’s work involving Eco treated wood.

The Liquor Liability Exclusion contains an exception for furnishing alcohol to someone, over 100 years old, who attributes their longevity to drinking one glass of red wine per day.

The self-defense exception, to the Expected or Intended Exclusion, has been amended and now reads as follows: “‘Bodily injury’ or ‘property damage’ expected or intended from the standpoint of the insured. This exclusion does not apply to ‘bodily injury’ resulting from the use of reasonable force to protect persons from eating vegetables sprayed with pesticides.”

The Who is an Insured section is expanded to include the following: 1. If you are designated in the Declarations as: f. A food cooperative, you are an insured. Your members are also insureds, but only with respect to the conduct of your business and while wearing Birkenstocks.

Late notice is excused if the reason for the delay is that someone prevented any carbon emissions by walking to hand-deliver the claim to the insurer.

“Other Insurance” clause is now simpler: “If there’s other insurance we’ll all just get together at Whole Foods, have some kale, and figure out how to share it fairly. |

| |

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

[REMAINDER OF PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

I’ve always wanted to write that.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Check This Out: All Sorts Of Coverage Opinions-Related Things Make The News

|

|

|

|

In the past month or so there have been all sorts of things with a connection to Coverage Opinions that have made the news. All of these happening at once is really odd.

Ben Brafman Reps Harvey Weinstein

The September 13, 2017 issue of Coverage Opinions featured an interview with renowned criminal defense lawyer Ben Brafman. In early November, it was reported that Brafman was retained to represent Harvey Weinstein against possible sexual assault charges in New York.

The “Bee Girl” Gets Married

The October 11, 2017 issue of Coverage Opinions featured an interview with Rogers Stevens, guitarist for Blind Melon, the band that rose to stardom in 1992 after the video for its song “No Rain,” featuring a young girl in a bee costume, exploded on the MTV airways. It was reported that the “bee girl” – Heather Deloach, now 34 – was married in late October in San Diego. The flower arrangements were adorned with tiny golden bees and the flower girls wore antennae similar to what Deloach wore for the video.

The Tom Petty Coincidence

The October 11, 2017 issue of Coverage Opinions featured an interview with Judge Jonathan Goodman, of the Southern District of Florida, on the judge’s Tom Petty fandom and several-times use of Tom Petty song lyrics in his opinions. In early November newspapers published a cartoon, from Bizarro, featuring a judge on the bench, with eyes closed and headphones in his ears. A lawyer is standing before the bench and saying to the judge: “Excuse me, Your Honor. We all miss Tom Petty, but…we can hear you singing.”

Sluggerrr Gets Inducted Into The Mascot Hall Of Fame

My favorite Coverage Opinions case is the one involving the Kansas City Royals mascot Sluggerr, an adorable furry lion, who tossed a hotdog into the stands, hit a fan in the eye and caused serious injuries. It produced a litigation saga that went all the way to the Missouri Supreme Court on the issue of whether the fan assumed the risk and how getting hit by a flying hotdog compares to get hit by a foul ball. In early November Sluggerrr was inducted into the Mascot Hall of Fame in Whiting, Indiana. He is only the fourth Major League Baseball mascot to enter those hallowed halls (Phillie Phanatic, Mr. Met and the Cleveland Indians’ Slider).

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Coming Soon: The 4th Edition Of “Insurance Key Issues”

|

|

|

|

At long, long last, work on the 4th Edition of General Liability Insurance Coverage - Key Issues in Every State is just about finished. We are optimistic that it will be available for sale in March. The number of new cases addressed, since 2014, is staggering. Thank you for all of the nice notes that I have received from readers asking when the book will be available for sale. Knowing that so many people are looking forward to it makes all of the effort to do the update worthwhile.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6 - Issue 9

December 13, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Encore:

Declarations: The Coverage Opinions Interview With The Grinch Who Stole Insurance |

| |

|

| |

To an outsider it seems like a simple operation. Not to mention astonishing. Do no advertising. Orders flood in from around the globe. Be loved by everyone. And work just one month out of the year. But the truth is that Santa Claus’s operation is much more complicated and not always so jolly. The amount of things that can, and do, go wrong is legion. Few know this but the bearded one has an insurance program as complex as that of a drug manufacturer.

It wasn’t always this way. “Why on Earth would I need insurance?,” Santa would say to the insurance agents constantly making pitches to him while their kids were bouncing on his lap. “Insurance? Who would sue Santa Claus?,” he would ask incredulously while letting out a big belly laugh.

But times change. In ‘68 some heathens in Philadelphia booed Santa. And two years later someone did the unthinkable and sued Santa. The reindeer came in for a hard landing and damaged a few shingles on a roof. It was minor. But Santa got dragged into court -- mumbling all the way about no good deed going unpunished. After that Blitzen bit off a kid’s finger and the family was pretty frosty. The floodgates were now open. Insurance became one of Santa’s biggest expenses. He stopped delivering gifts to trial lawyers’ houses.

For the past four decades Santa’s insurance has been written by Arctic Insurance Group. But despite all of Arctic’s promises to bail him out of trouble, it has been quite the opposite. Santa’s success at getting claims paid has resembled that of the Cubs. [Remember, this was originally published a year ago.] And the reason for this is easy to explain – for the past 33 years Santa’s claims were assigned to the Insurance Grinch. The Insurance Grinch found just about every way possible to disclaim coverage for just about every claim that Santa presented. His skills were unparalleled. When Santa began to get inundated with claims for knocking out Dish Network service with his sleigh, the Insurance Grouch disclaimed coverage on the basis of the aircraft exclusion. Wow! Now that’s impressive.

Good news for Santa -- the Insurance Grinch recently retired. He’s headed to Minnesota to enjoy the warmer weather. He bought a house in a neighborhood with lots of kids so he can tell them to get off his lawn. Even though the Insurance Grinch is not a subscriber – he finds that Randy Spencer column to be annoying -- he agreed to give an exclusive interview to Coverage Opinions addressing a claims career like none other.

Coverage Opinions: Thank you Insurance Grinch for taking the time to discuss your 30+ year career handling Santa’s claims. Were the other adjusters jealous that you handled such a fascinating and unique account?

Insurance Grinch: Very much so. But not because I was handling Santa’s claims. Because it meant that I didn’t have to deal with any construction defect claims.

CO: What was your favorite thing about handling Santa’s claims?

IG: When you put on your Match.com profile for “occupation” that you handle Santa Claus’s insurance claims it makes a lot of people want to meet you.

CO: What was the most common claim from Santa that you handled?

That’s easy. A kid would ask Santa for something – like an iPad. And he’d wake up on Christmas morning and find a sweater. Then, just as day follows night, in rolled the claim against Santa for breach of contract and detrimental reliance.

CO: How did you handle these?

IG: Well, there was no “bodily injury,” “property damage” or “personal and advertising injury” to trigger CGL coverage. And several years ago the North Pole Supreme Court held that, when Santa opens a letter from a youngster, it qualified as the formation of a contract. I know. It’s crazy, right. But it’s a liberal bench up here. But once the court found that an opened letter was a contract, it became easy to disclaim coverage since the professional liability policy has a breach of contract exclusion.

CO: Tell me about that claim where Blitzen bit off a kid’s finger?

IG: The kid was visiting Santa on a school trip and handing Blitzen a carrot. Except the kid was holding it in front of Blitzen’s mouth and the pulling it away. Holding it in front of his mouth and the pulling it away. The kid deserved it. I’m pretty sure Blitzen did it on purpose. At least I hope he did.

CO: Was it covered?

IG: No. We had a reindeer exclusion in all of the policies. I know. It seems strange given that the reindeer are such an essential part of Santa’s operation. But Santa didn’t read the policy. At least not until it was too late. And the broker was asleep at the switch. So we were able to get it in. And we have refused to take it out. We’re the only insurer in the North Pole. So where else is Santa going to go.

CO: What was the most expensive claim that you handled?

IC: One year Santa was in someone’s living room and his toy sack knocked a vase off a table. Turns out it was from the Ming Dynasty. Worth two million. The homeowner’s insurer paid for it. We were sure a subro claim would be made. We kept waiting but it never came in. Word on the street was that the homeowner’s carrier was afraid of the bad press from suing Santa.

CO: Were there any unique liability issues involving Santa?

IG: Many years ago the North Pole Supreme Court held that Santa can be liable for a defective product under the Restatement of Torts 402(A). As you can imagine, this opened Santa up to massive products liability exposure – defective BB guns, Easy Bake Ovens that start a fire, Parcheesi pieces that get swallowed. He was never able to get products coverage after that.

CO: You don’t get too many visitors up here. Seems like Santa’s premises exposure was pretty minimal.

IG: True. Not many make their way here. No direct flights. But that didn’t stop Santa from having premises liability exposure. Santa never shoveled the snow. He blamed a bad back but I think he was just lazy. The mail man would come ten times a day during the busy season and constantly wipe out on ice while walking up Santa’s driveway. Santa knew it was going to happen. Finally we said enough is enough and disclaimed coverage based on no “occurrence.”

CO: Were there are claims that involve Coverage B of the CGL policy?

IG: One in particular. Santa would put a kid on the naughty list. The brat would turn around and sue for defamation. But we were successful in knocking these out of coverage on the basis that there was no “publication” of the kid’s naughty status. The only one who knew was the kid himself when he received the mandatory ten-day notice letter from Santa.

CO: What about the elves. Did they ever cause any trouble for Santa?

IG: Look, this was a big operation. At peak time the elves work 16 hour days. What choice did Santa have? Work the elves to death or disappoint a kid in Cedar Rapids who wanted a fire truck. So of course there were some wage and hour and overtime disputes. But we had an exclusion for this. The elves also got hurt fairly regularly. All the uncovered lawsuits required Santa to cut some corners on safety. Thankfully we didn’t write the comp.

CO: Did Santa ever damage any chimneys? Let’s face it, he’s not exactly svelte.

IG: All the time. But that was an easy one to handle. Those claims fit right into the exclusion for property damage to that particular part of real property on which you are performing operations.

CO: Any other interesting things about Santa’s risk program?

IG: We require Santa to be an additional insured on all of the mall Santa’s policies. Not surprisingly, Santa sometimes gets brought into a suit against a mall Santa who did something stupid. But Santa didn’t police their policies so he was never an additional insured. And we had an exclusion for Santa’s failure to secure AI rights.

CO: I’m starting to wonder – were any claims covered?

IG: Of course. Back in ’98 we paid a claim. Wait. It might have been ’97. A tike fell off Santa’s lap. We looked at everything but just couldn’t find a reason to disclaim. We thought about no “occurrence” since it seemed like faulty work. The kid is supposed to stay on Santa’s lap. He fell off. That sure sounded faulty to me. But in the end we settled and wrote a check. The policy had a pretty low sub-limit for claims arising out of, based on, in connection with or related to kids falling off Santa’s lap.

CO: Have you been training your successor?

IG: I have. But he still has a long way to go. On my last day in the office he got in a claim from a germaphobe family saying that Santa sneezed on their son. The kid is seeking medical monitoring for the rest of his life. The new adjuster was ready to appoint counsel. I said not so fast. Sounds like the pollution exclusion.

CO: What advice did you give to your successor?

IG: I explained to him that the vast majority of the claims come in the door in January and February. If he’s doing his job he’ll have them all disclaimed by the end of March. After that the key is to pretend to be busy for the next nine months.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

From Boo To Sue:

Maniloff Publishes Halloween Op-Ed In USA Today On Haunted Houses Liability

|

|

|

|

|

| |

As someone who enjoys looking at the lighter side of the legal system, and especially fun judicial decisions, it was a real thrill to publish an Op-Ed, in USA Today, that examines the critical issue of whether a haunted house is liable for injuries sustained on account of a visitor being scared. Yes, several appellate court decisions exist addressing this issue.

It’s actually an interesting tort issue. All sorts of legal duties are imposed on businesses to ensure that their visitors are free of danger. This seems simple enough. Unless you run a haunted house – designed to frighten your guests. Those shelling out cash to tour such an attraction would be disappointed if steps were taken to remove all perils. But what if the fright goes further than planned and leads to an injury? Is the haunted house operator liable when the injured person gets exactly what they paid for and then goes from boo to sue?

I hope you’ll check out this USA Today piece, published on Halloween, that examines how some appellate courts have resolved these competing interests:

http://www.coverageopinions.info/USAToday.pdf

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

John Grisham Says Insurance Law On The Bar Exam

|

|

|

|

| |

I recently re-read John Grisham’s masterpiece – The Firm. It was just as great as it was 25 years ago. Having read all 33 of Grisham’s books (including his riveting non-fiction The Innocent Man), I vote The Firm as his best, with a lot of very close seconds. [Others in my top 5: The Rainmaker (“You must be stupid, stupid, stupid!”); The Broker; A Painted House; The Associate]

When I read The Firm 25 years ago I would have never paid attention to Grisham’s description of the subjects on the Tennessee bar exam. But this time around, when I saw that they included insurance law, I had a holy cow moment

Of course, insurance is not really on the Tennessee bar exam. But it’s not surprising that Grisham said it was. He readily admits that he doesn’t do much research for his books and resorts to just making stuff up. To see a great example of this, read Camino Island and then the Author’s Note at the end.

So while insurance law is not on the Volunteer State’s bar exam, it’s nice to see that someone thought it was worthy. In fact, that’s probably why The Firm was dubbed a legal thriller. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Pet Insurance: My Dog’s Medical Diagnosis

|

|

|

|

|

|

My dog Barney has pet insurance. Reasonable minds can differ on whether that’s a good financial deal or not. I guess it was the year he tried to eat the drainage pipe for the gutters. Other years I’m not as sure.

But I don’t think anyone can disagree that the diagnosis on his last claim summary probably didn’t come from Black’s Veterinary Dictionary. [I know. Me neither. I had no idea that Black’s also had a veterinary dictionary]. I’m pretty sure there is no World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases Code for this:

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

The Most Important Key On Your Key Board

|

|

|

|

I’m not sure how it took me 20+ years of doing insurance coverage work to figure this out: |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Frank Malpigli On The Duty To Defend That Does Not End

|

|

|

|

I always enjoy the annual insurance issue of DRI’s “For the Defense” magazine that features several lengthy articles addressing coverage topics. The October 2017 issue contained, as always, several excellent pieces. One in particular that I really enjoyed, and recommend for your reading, is “An Insurer’s Continued Duty to Defend After All Covered Claims Are Dismissed,” by Frank Malpigli of Miranda Sambursky Slone Sklarin Verveniotis LLP in Mineola, New York.

Many thousands of courts have addressed whether a duty to defend is owed. In other words, has a duty to defend begun? Yet very few courts, by comparison, have addressed when a duty to defend ends. What’s more, of the decisions that have, many are written is broad strokes -- such as, an insurer’s duty to defend ceases when all potentially coverage claims have been eliminated or dismissed, or something along those lines.

As Frank Malpigli demonstrates in his excellent piece, insurers face a risk of continuing to defend suits that certainly appear to no longer contain any potentially covered claims.

|

|

|

|

|

Frank’s piece is lengthy and I do not want to do it a disservice by trying to summarize all of it here. The crux of it, with substantial supporting case law, is this. Two of the leading cases addressing when a duty to defend ends (or not) are Commerce & Industry Insurance Co. v. Bank of Hawaii (Haw. 1992) and Meadowbrook, Inc. v. Tower Insurance Co. (Minn. 1997). In both cases, involving multiple claims, all of the arguably covered claims had been dismissed. However, these two state supreme courts held that the insurer’s duty to defend could not be terminated until there were no further rights to appeal. Thus, the insurers were required to continue to defend uncovered claims, since the covered claims, although dismissed, still had appellate rights attached to them. Other courts have reached the same conclusion -- some based on Bank of Hawaii and Meadowbrook and some based on other reasons.

Frank notes that “[t]he interesting and somewhat perplexing approach in these cases [Bank of Hawaii and Meadowbrook and others] is that the courts based the insurers’ continued duty to defend on the finality of a claim. They did not delve into discussing whether the language within the policy supported such liberal interpretation. In fact, in coming to their conclusions, the courts added language to the policies where none existed.”

The take-away of Frank’s piece is that, without specifically addressing, in their policies, when a duty to defend ceases, insurers are placing themselves at risk for courts subjecting them to an obligation to continue to defend suits that certainly appear to no longer contain any potentially covered claims. Frank counsels that insurers should consider addressing, in their policies, when they may properly withdraw defense counsel.

I recommend that you check out Frank Malpigli’s article, “An Insurer’s Continued Duty to Defend After All Covered Claims Are Dismissed,” in the October issue of DRI’s “For the Defense” magazine.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Policy’s Mistaken Semicolon Gives Rise To Coverage

|

|

|

|

We all know that, when it comes to insurance policies, language is king. Coverage can turn on fine point distinctions in the meaning of words or seemingly minutiae-like differences between the choice of one term over another – even “an” versus “the” can be the difference between millions of dollars in coverage. In Lee v. Mercury Insurance, No. A17A0624 (Ga. Ct. App. Nov. 3, 2017) the Court of Appeals of Georgia took the rule, that policy language is king, to another level – coverage turned on the existence of a semicolon.

At issue was coverage for a residence destroyed by fire. I’ll try to simply the facts. Ronald Lee traveled frequently for work. To help a childhood friend, in financial distress, Lee purchased his home in Riverdale, Georgia, and allowed him and his family to continue to live in it free of charge. As part of the arrangement, Lee could stay there when he was flying through Atlanta. When Lee first took out the mortgage on the home he stayed there so many nights each week that the mortgage company considered it his primary residence. Later, he stayed there “maybe one night a week, every other week, or something.”

The home was destroyed by fire, killing Lee’s friend. Lee sought coverage for the loss from his homeowner’s insurer, Mercury Insurance. Mercury disclaimed coverage. Lee filed suit against Mercury alleging various theories of recovery. The trial court granted Mercury’s motion for summary judgment, that no coverage was owed, based on Lee’s failure to reside at the house as required by the terms of the policy. The case went to the Georgia appeals court on various issues.

For purposes here, the policy provided coverage as follows:

The “COVERAGE A — DWELLING” “We cover: the dwelling on the residence premises shown in the Declarations used principally as a private residence, including structures attached to the dwelling; materials and supplies located on the residence premises used to construct, alter or repair the dwelling or other structures on the residence premises.”

The policy defined “residence premises” as: “the one, two, three or four family dwelling, condominium or rental unit, other than structures and grounds, used principally as a private residence; where you reside and which is shown in the Declarations.” (semicolon not giant in the original).

The court didn’t have much problem concluding that coverage was owed, even though the house at issue was not where Lee resided. The court stated: “Based upon the placement of the semicolon in the definition of ‘residence premises,’ a layperson could reasonably understand the defined term to mean ‘the one, two, three or four family dwelling condominium or rental unit, other than structures and grounds, used principally as a private residence’ or ‘where you reside and which is shown in the Declarations.’” (emphasis added).

Since the home at issue was a family dwelling used principally as a private residence, one of the two independent definitions of “residence premises” was satisfied. So it did not matter that the other one – “where you reside and which is shown in the Declarations” was not.

The court noted that, for the dissent to reach its conclusion, it was required to rewrite the policy by removing the semicolon. This the court was not willing to do.

The court was also influenced by the fact that Mercury used the same definition of “residence premises” in its policies covering secondary residences. Thus, under Mercury’s interpretation,

“a secondary residence, such as a beach or mountain home, would be not be covered under the policy form, even though it is undisputed that Mercury used the same policy form to insure secondary residences.” But, under the court’s interpretation of “residence premises,” the policy would be prevented from being illusory for secondary residences. That’s a compelling argument

In any event, you don’t need to be Aesop to see the moral here -- when it comes to insurance policies, language – all of it -- is king.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Cosgrove Returns: I’ve Never Seen This Before In A Coverage Case

This summer an Arizona federal district court issued Cosgrove v. National Fire & Marine Insurance Company. The court held that insurer-appointed defense counsel, in a reservation of rights-defended case, used the attorney-client relationship to learn that his client did not use subcontractors on a project. When defense counsel did so, he knew, or had reason to know, that his client’s policy contained a Subcontractors Exclusion and that the insurer may attempt to deny coverage based on the exclusion. Thus, the court held that the insurer was estopped from asserting the Subcontractor Exclusion as a coverage defense. The court reached this decision despite the existence, or not, of subcontractors being a pretty routine, and obvious, and not secret, fact in a construction dispute.

Needless to say, this was a very troubling decision for insurers (and appointed defense counsel). Very shortly after the court’s decision the parties settled. As part of the settlement, the court agreed that it would vacate and seal the summary judgment decision. Sure enough, you can’t get the decision on Pacer and the insurer arranged for the decision to be removed from Lexis and Westlaw. I have a copy of the decision, which is now a collector’s item and I keep it with my Joe Montana rookie card.

Get ready – On November 3, United Policyholders filed a Motion to Intervene to unseal and reinstate the decision. UP says in its brief that what the insurer did is an “impermissible tactic” – one “commonly employed by insurers in an attempt to reshape case law in their favor after an adverse ruling.” UP says that the insurer, faced with an adverse decision, is “seek[ing] to hide the court’s opinion.” The insurer filed a response, providing many reasons for denial of intervention – UP has no standing; the case is over; the judge agreed to vacate and seal the decision as a condition of settlement; the various requirements of the Intervention rule have not been satisfied…. Briefing on what is a seemingly unusual issue is ongoing.

Court Provides Primer On The “War Risk” Exclusion

Cases involving the “war risk” exclusion are few and far between. And that’s a good thing. So, on one hand, when one comes along, it’s worth looking at it. It’s like a coverage case eclipse, but no special glasses are needed to read it. On the other hand, since the war risk exclusion arises so infrequently – probably never for almost all coverage lawyers – there is a temptation to brush the decision aside as unimportant.

For those of you in the not brush it aside category I highly recommend that you check out Universal Cable Productions v. Atlantic Specialty Ins. Co., No. 16-4435 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 6, 2017), where the court provided a detailed analysis of the “war risk” exclusion in the context of a claim for losses sustained in 2014, by the producers of the television series Dig, on account of the need to move production of the show out of Israel, following hostilities between Israel and Hamas. [My wife watched Dig and enjoyed it. I watched the first two episodes but couldn’t get into it.]

The opinion is lengthy, addressing the hostilities at issue, the history and nature of Hamas, definitions of war and case law addressing the “war risk” exclusion. The court concluded that the conflict between Israel and Hamas, in 2014, constituted war. Thus, the “war risk” exclusion precluded coverage for the losses sustained by the show’s producers. It is well beyond the scope of a “Tapas” article to address the opinion in detail. In the event of future war risk coverage litigation I would expect to see courts look to Universal Cable Productions for guidance, given how detailed the opinion is.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6 - Issue 9

December 13, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction And Selection Process

Welcome to the 17th annual look back at the year’s ten most significant insurance coverage decisions. Holy Cow! It’s been that long?

As I always do at the outset of the annual Top 10 Coverage Cases of the Year, here is my description of the selection process. It is highly subjective, not in the least bit scientific and in no way democratic. But just because the selection process has no accountability or checks and balances whatsoever does not mean that it wants for deliberativeness. To the contrary, the process is very deliberate and involves a lot of analysis, balancing, hand-wringing and tossing and turning at night. It’s just that only one person is doing any of this.

[If you think I missed a case, tell me. I’ll be the first to admit that I goofed (and I have). It is impossible to be aware of every coverage case decided nationally.]

The selection process operates throughout the year to identify coverage decisions (usually, but not always, from state high courts) that (i) involve a frequently occurring claim scenario that has not been the subject of many, or clear-cut, decisions; (ii) alter a previously held view on an issue; (iii) are part of a new trend; (iv) involve a burgeoning or novel issue; or (v) provide a novel policy interpretation. Some of these criteria overlap. Admittedly, there is also an element of “I know one when I see one” in the process. In addition, cases that meet the selection criteria are usually not included when the decision is appealed. In such situation, the ultimate significance of the case is up in the air.

In general, the most important consideration for selecting a case as one of the year’s ten most significant is its potential ability to influence other courts nationally. Many courts in coverage cases have no qualms about seeking guidance from case law outside their borders. In fact, it is routine--especially so when in-state guidance is lacking. The selection criteria operates to identify the ten cases most likely to be looked at by courts on a national scale and influence their decisions.

That being said, the most common reason why many unquestionably important decisions are not selected is because other states do not need guidance on the particular issue, or the decision is tied to something unique about the particular state. Therefore, a decision that may be hugely important for its own state – indeed, it may even be the most important decision of the year for that state – nonetheless will be passed over as one of the year’s ten most significant if it has little chance of being called upon by other states at a later time.

For example, this year the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in Rancosky v. Washington National Insurance Co., set forth the elements for establishing a bad faith claim. The significance of Rancosky, for lawyers practicing in Pennsylvania, cannot be overstated. However, the decision was not considered for inclusion in the annual Top 10 Best in Show. There is simply no shortage of case law nationally addressing bad faith standards. Thus, the chances of a court, outside of Pennsylvania, turning to Rancosky for guidance, when confronted with a bad faith case, are slim.

Likewise for the Missouri Supreme Court’s decision in Doe Run Res. Corp. v. Am. Guar. & Liab. Ins., addressing -- first impression -- whether the pollution exclusion bars coverage for a toxic tort claim arising from alleged industrial pollution. This is a very important decision for those practicing in Missouri. But courts in other states, when confronting the pollution exclusion, are not likely to look to Doe Run and say -- Show Me.

I gave a lot of thought to including the Washington Supreme Court’s decision in Xia v. ProBuilders Specialty as a top ten case. The court – the first ever, anywhere – used an “efficient proximate cause” analysis, when interpreting the pollution exclusion, resulting in a significant narrowing of its potential applicability (as well as expansion of what’s bad faith). But with a volume of case law nationally, interpreting the pollution exclusion, that could fill a library -- and the decision involving such a seismic change in its interpretation -- I do not see Xia having impact outside of Washington.

Best wishes for a healthy and prosperous 2017 and may any resolutions that you make last at least until February.

The year’s ten most significant insurance coverage decisions are listed in the order that they were decided.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Long v. Farmers, 388 P.3d 312 (Or. 2017)

Insurer’s Potential Obligation To Pay Prevailing Party Attorney’s Fees Dramatically Broadened

|

|

|

|

When an insurance company is evaluating whether to file a declaratory judgment action or defend one filed against it, the principal issues under consideration are likely to be its chance of success and the amount of attorney’s fees that it will incur to achieve the desired result. But there is another factor that should also be included in the risk evaluation: possibly having to pay the policyholder’s attorney’s fees. I sometimes (a lot of times, in fact) see this consideration overlooked, or not given enough weight, in the calculus. After all, it is a potential factor in 45 states. In my experience this is the most overlooked coverage issue.

A recent decision from the Oregon Supreme Court involves a dramatic broadening of the scenarios under which an insurer may have to pay the policyholder’s attorney’s fees. Essentially, the policyholder does not have to be a prevailing party, as that term is usually understood to mean.

Despite our legal system’s bedrock principle, that the losing party is not obligated to pay the prevailing party’s attorney’s fees, insurance coverage litigation is an exception. In the vast majority of states -- almost all in fact -- the possibility exists, in some way, shape or form, that the insurer may be obligated to pay some, or all, of a successful policyholder’s attorney’s fees in addition to the amount of the claim.

One commonly cited rationale for this exception is that, if the insured must bear the expense of obtaining coverage from its insurer, it may be no better off financially than if it did not have the insurance policy in the first place. The specific approaches to this insurance exception vary widely by state and can have a significant impact on the likelihood of the insurer in fact incurring an obligation for its insured’s attorney’s fees.

Some states have enacted statutes that provide for a prevailing insured’s recovery of attorney’s fees in an action to secure coverage. Other states achieve similar results, but do so through common law. But whichever approach applies, the most important factor is the same: whether the prevailing insured’s right to recover attorney’s fees is automatic or must the insured prove that the insurer’s conduct was unreasonable or egregious in some way.

For example, a Hawaii statute mandates an award of attorney’s fees without regard to the insurer’s conduct in denying the claim. In other words, it imposes strict liability for attorney’s fees on an insurer that is ordered to pay a claim. Maryland also takes a strict liability approach, but it is the result of a decision from its highest court. A Virginia statute departs from strict liability and permits an award of attorney’s fees, but only if there was a finding that the insurer’s denial of coverage was not in good faith. Connecticut also rejects a strict liability rule, but it was established judicially and not legislatively. A handful of states use a combination of legislative and judicial avenues to address whether attorney’s fees are to be awarded to a prevailing insured. Under this hybrid approach, consideration is first given to the state’s general statute that allows for an award of attorney’s fees in an action on a contract. The court then interprets this statute, covering contracts in general, to include an insurance contract dispute. And some states address the issue by applying their general statutes permitting an award of attorney’s fees against a party that engages in frivolous or vexatious litigation.

While the mechanisms vary, in almost all cases an insurer that is unsuccessful in coverage litigation will either be automatically obligated to pay for its insured’s attorney’s fees or may be litigating post-trial whether such obligation exists. Whichever the case, the potential for being saddled with the attorney’s fees incurred by its prevailing insured in a declaratory judgment action is a consideration that insurers will usually not be able to avoid.

A recent decision from the Oregon Supreme Court demonstrates in stark terms how significant the attorney’s fees issue can be for an insurer that is unsuccessful in coverage litigation. The obligation can arise even if there’s no decision in the coverage case. While the case involves an Oregon statute, and there is no shortage of case law nationally addressing the ins and outs of prevailing party attorney’s fees, I still believe that the case has the ability to influence courts nationally. Thus, I included it as a top ten case of 2017.

In Long v. Farmers Ins. Co., the Oregon Supreme Court addressed the state’s statute -- ORS 742.061(1) -- that creates the potential for an insured to recovery its attorney’s fees in coverage litigation. The statute provides as follows: “Except as otherwise provided in subsections (2) and (3) of this section, if settlement is not made within six months from the date proof of loss is filed with an insurer and an action is brought in any court of this state upon any policy of insurance of any kind or nature, and the plaintiff's recovery exceeds the amount of any tender made by the defendant in such action, a reasonable amount to be fixed by the court as attorney fees shall be taxed as part of the costs of the action and any appeal thereon.” (emphasis added by court)

The case is lengthy and I want to keep this short and simple.

The insured argued that, if you file an action on an insurance policy, and you later obtain more from the insurer – even if through the insurer simply voluntarily paying you more -- than the insurer tendered in the first six months after proof of loss, then you are entitled to recover attorney’s fees. In other words, the insured argued that “recovery” “refers to any kind of restoration of a loss, including a voluntary payment of a claim made after an action on an insurance policy has been filed.”

We are Farmers, bum ba dum bum bum bum bum, argued that “recovery,” as used in the statute, means a “money judgment in the action in which attorney fees are sought. Under that interpretation, attorney fees may be had for an insured’s action on a policy only if the insured obtains a money judgment that exceeds any tender made by the insurer within the first six months after the insured offers proof of loss.”

The court found for the insured, holding that “when an insured files an action against an insurer to recover sums owing on an insurance policy and the insurer subsequently pays the insured more than the amount of any tender made within six months from the insured’s proof of loss, the insured obtains a ‘recovery’ that entitles the insured to an award of reasonable attorney fees.” (my emphasis added).

In other words, as the court put it: “A declaration of coverage is not sufficient to make ORS 742.061 applicable; an insured must obtain a monetary recovery after filing an action, although that recovery need not be memorialized in a judgment.” (emphasis added by court).

Putting aside the court’s lengthy analysis, and numerous arguments back and forth between the parties, the court rested its decision on the purpose of the statute: “The purpose of ORS 742.061 is to discourage expensive and lengthy litigation. Requiring the insurer to pay the insured’s attorney fees if and only if the insured obtains more in the litigation than was timely tendered advances that purpose insofar as it encourages insurers to make reasonable and timely offers of settlement and also encourages insureds to accept reasonable offers and forego litigation. But the statute also serves a compensatory purpose. The statute ensures that, when insureds file suit to obtain what is due to them under their policies, they do not win the battle but lose the war by expending much or all of what they obtained in the litigation on attorney fees. . . . The function that a ‘recovery’ plays in that overall framework is to establish that the insured indeed obtained something in the action—payment of benefits due under the insurance policy that exceeded any amount that the insurer timely tendered. . . . It was [in the examples provided] the insurer’s payment, not the form of payment, that entitled the insured to attorney fees.”

On one hand, as Long v. Farmers addresses an Oregon statute, you could write the decision off as being limited to Oregon. However, I believe that the decision has the potential for wider reach. Given that the decision was tied to the general rationale for allowing an insured to recover attorney’s fees – prevent the insured from winning the battle and losing the war; which is the same rationale used by many states -- other states may consider allowing an insured to do so, even if coverage was not obtained through judicial decree.

I also do not believe that, because the claim at issue involved first-party property, the Long decision is necessarily so limited. First, case law demonstrates that the Oregon statute is not limited to first-party property policies. Second, again, the Long decision was tied to the overarching rationale for allowing an insured to recover attorney’s fees. And that rationale is cited by courts in both property and liability cases.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Walsh Construction Company v. Zurich American Ins. Co., 72 N.E.3d 957 (Ind. Ct. App. 2010)

SIR Obligation Applies To The Additional Insured Too

|

|

|

|

Walsh Construction Company v. Zurich American Ins. Co. finds a place on this list for two reasons. First, the case involves an issue that has the potential to arise with some frequency, but has not been the subject of much case law. Second, the decision provides a lesson in policy drafting for insurers (as well as risk management for general contractors – any who actually read this).

At issue in Walsh is whether a self-insured retention, and a large one at that, applies to an additional insured. The Court of Appeals of Indiana characterized the decision as one of first impression in the state, as well as noting that the four foreign cases cited by the parties were not on all fours. Thus, clearly, the issue has not been the subject of much judicial review. Yet, it certainly has the potential to arise with some frequency when you consider how common additional insured issues are in general.

Walsh grows out of a common claim scenario. Walsh, a general contractor, hired Roadsafe Holdings, to be Walsh’s subcontractor on a traffic project. Walsh’s contract required Roadsafe to procure a commercial general liability insurance policy and name Walsh as an additional insured on a primary and noncontributory basis. Roadsafe obtained a CGL policy from Zurich. An endorsement named, as additional insureds, “any person and organization where required by written contract.” However, Roadsafe’s policy with Zurich contained a $500,000-per-occurrence self-insured retention.

Boguslaw Maczuga was injured while operating his motor vehicle through the work zone’s traffic pattern. Maczuga sued Walsh. Walsh notified Zurich and sought a defense from the insurer on the basis of being an additional insured. Zurich denied Walsh’s tender and Walsh filed a complaint for declaratory judgment.

Among other things, Zurich asserted that, based on the SIR endorsement, Walsh was required to pay the first $500,000 of costs. [I suspect that Walsh was unaware that Roadsafe’s CGL policy contained an SIR, especially such a significant one. If that’s the case, Walsh certainly could have found that out before it got in this situation.]

The trial court found for Zurich. On appeal, Walsh and Roadsafe argued that the SIR endorsement amended only Zurich’s relationship to Roadsafe and did not amend Zurich’s obligations with respect to Walsh.

The appellate court also found for Zurich. The court based its decision on the following language from the policy:

“Self-insured retention” means: the amount or amounts which you or any insured must pay for all compensatory damages and “pro rata defense costs” which you or any insured shall become legally obligated to pay because of damages arising from any coverage included in the policy.

The “self-insured retention” amounts stated . . . apply as follows: 1. If a Per Occurrence Self Insured Retention Amount is shown in this endorsement, you shall be responsible for payment of all damages and “pro rata defense costs” for each “occurrence”[] until you have paid damages equal to the Per Occurrence amount .

With “you” meaning the named insured – Roadsafe – the court concluded that “[t]he SIR endorsement shifts the initial cost burden from Zurich to Roadsafe, the named insured, not just for Roadsafe’s damages and defense costs but also for any additional insured’s damages and defense costs. As such, the SIR endorsement amends Zurich's obligation under the CGL policy to defend Walsh by placing the first $500,000 of that burden on Roadsafe.”

Thus, not only did the court conclude that the SIR could not be avoided for Walsh as an additional insured, but that Roadside was obligated to pay it.

In addition to this “plain reading of the SIR endorsement,” the court found support in other provisions of the policy, such as “the SIR endorsement unambiguously conditions Roadsafe’s compliance with its provisions as a ‘condition precedent to coverage’ from Zurich. And there is no rational basis to apply the SIR endorsement as a condition precedent to Zurich’s coverage of the named insured but not to Zurich’s coverage of additional insureds.” The court also noted that the SIR enabled Roadsafe to obtain the CGL policy from Zurich at a reduced premium.

Held: “Taken together, those provisions unambiguously manifest the intent of the parties to the contracts, Zurich and Roadsafe, for the SIR endorsement to control their relationship such that Roadsafe assumed all costs and liability for the first $500,000 of any claim that might be made under the CGL policy, regardless of whether that claim was against Roadsafe or an additional insured.”

The decision is very much tied to the policy language. And policies can vary widely in how they address SIR obligations. But that does not diminish the potential significance of the decision. As it is still just one of few in the area, it simply means that parties will address whether their language is sufficiently similar to that at issue in Roadsafe or distinguishable, such that a different result is warranted. Of significance, while the court noted that the SIR enabled Roadsafe to obtain the policy from Zurich at a reduced premium, that alone would not have likely made a difference in the face of policy language that did not support Zurich’s position.

Because the decision turns on policy language it is also a cautionary tale for insurers to address their SIR terms to ensure that a policy, priced for an SIR, does not become “dollar one” for an additional insured.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

Thompson v. National Union Fire Insurance Company, 249 F. Supp. 3d 606 (D. Conn. 2017)

O-CIP! Is It A Wrap For The Wrap-Up Exclusion? (Underwriters Take Note)

|

|

|

|

Insurers that rely on exclusions in their policies, to eliminate coverage for their insureds’ projects that are covered under wrap-up policies, have much to take away from the Connecticut District Court’s decision in Thompson v. National Union Fire Insurance Company (applying Georgia law). The court held that a wrap-up exclusion, contained in a commercial umbrella policy, was ambiguous, and, hence, did not apply to a $13.5 million exposure. The case is brief. But when it comes to judicial opinions – size does not matter.

While Thompson is a federal district court decision, and claims involving the possible applicability of a wrap-up exclusion do not arise every day, I selected the case for inclusion here for two reasons. First, the decision – the only one I know of like it -- is an invitation for policyholders, in every case involving a wrap-up exclusion, to attempt to argue that the exclusion is ambiguous. Second, any insurers that rely on wrap-up exclusions, to eliminate coverage under their “practice policies,” need to take a hard look at such exclusions and decide whether to make any changes, to avoid potentially paying $13.5 million for a claim that was clearly not intended to be covered.

Thompson involves coverage for a contractor, Bluewater Energy Systems, that was sued following a power plant explosion. Individuals and estates that were harmed by the blast obtained a judgment for $13.5 million and brought an action against Bluewater’s umbrella insurer.

The insurer maintained that no coverage was owed on account of the policy’s “wrap-up” exclusion, which provided: “This insurance does not apply to . . . any liability arising out of any project insured under a wrap-up or similar rating plan.”

The insurer’s position was that no coverage was owed because the power plant project was insured under a contractor controlled insurance program, which the insurer contended is a type of “wrap-up” program.

The plaintiffs -- those affected by the explosion -- argued what you would expect: there are lots of reasonable interpretations of the wrap-up exclusion, and, because it was drafted by the insurer, the operative language must be read strictly against the insurer and in favor of providing coverage. The court agreed that the wrap-up exclusion was ambiguous.

A couple of the plaintiffs’ arguments, that led to this finding of ambiguity, are specific to the case. Those certainly offer lessons. But one of the plaintiffs’ arguments was very general. And that one should cause insurers, that rely on wrap-up exclusions, to sit up and take notice.

As for the issues specific to the case, the plaintiffs argued that the project had only a partial contractor controlled insurance program and it did not provide coverage to all of the project’s participants and did not provide property damage or “builders risk” coverage. “If defendant wanted to exclude coverage for any project that ‘involves’ a wrap-up or is ‘in any way’ affiliated with a consolidated insurance program, it should have explicitly included such limitations and defined the term ‘wrap-up.’” Second, because the contractor controlled insurance program at issue has been exhausted, no coverage remains. Hence, the plaintiffs’ remaining claims are not “insured under” the program.

But the court’s reason for finding the wrap-up exclusion ambiguous, that should cause insurers the most concern, is this: “Plaintiffs contend that defendant has failed to show that ‘wrap-up’ has one peculiar meaning and cannot legitimately argue that ‘wrap-up’ has one, unambiguous meaning when its own policies and witnesses define the term in a number of distinct ways.”

It’s one thing not to define a term in a policy. Not every term in any insurance policy can be defined (despite what some policyholders and courts sometimes say). But if in fact an insurer’s own policies and witnesses define a term in a number of distinct ways, the court’ job -- especially when it’s reading a policy strictly against the insurer -- is being made easy.

Postscript: For an excellent article addressing numerous coverage issues, under wrap-up policies, see “Wrap-Up Insurance Coverage,” by Margaret Glass, of Gieger, Laborde & Laperouse, LLC, in the October 2017 issue of DRI’s “For the Defense” magazine.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 6, Iss. 9

December 13, 2017

In Re National Lloyds Insurance Company, No. 15-0591, 2017 Tex. LEXIS 522 (Tex. June 9, 2017)

Policyholder To Insurer On Attorney’s Fees: I’m Showing You Mine, You Show Me Yours

|

|

|

|

The possibility that an insurer will have to pay its policyholder’s attorney’s fees, in a coverage action, is one that exists – in one form or another – in 45 states. For more about this see the discussion above in Long v. Farmers.

Once it is determined that an insurer is obligated to pay its policyholder’s attorney’s fees, another question usually arises -- How much must be paid, i.e., are the fees reasonable? There is a substantial amount of case law nationally that has addressed this issue. One consideration in that calculus can be the amount of the insurer’s attorney’s fees. In other words, if an insurer is going to allege that the policyholder’s fees are excessive, the policyholder may then decide to serve discovery on the insurer, seeking to learn the amount of its fees. The policyholder’s argument being – how can you, insurer, say our fees are excessive, when you spent just as much in the case, or more? Of course, the risk of backfire for a policyholder, in seeking such information, is obvious.

Whether a policyholder in a coverage dispute was entitled to obtain the insurer’s counsel’s billing records was at issue before the Supreme Court of Texas in In Re National Lloyds Insurance Company. This is not the first case to address this issue. However, it may be the longest and most detailed decision. That, and coming from such an important supreme court, especially on coverage issues, is why I selected it for the 2017 Top Ten list.

The policyholder’s attorney’s fee claim arose out of coverage litigation for claims for hail damage under homeowner’s policies. The policyholders sought their fees as part of their statutory, contractual and extra-contractual claims. While no determination had been made that the policyholders’ fees were recoverable, they sought discovery of a host of insurer attorney-billing information.

The insurer objected on the basis that “the requested discovery is overly broad and seeks information that is both irrelevant and protected by the attorney-client and work-product privileges.” As for relevance, the insurer relied on a “stipulation that it ‘will not use its own billing invoices received from its attorneys; payment logs, ledgers, or payment summaries showing payments to its attorneys; or the hourly fees or flat rates being paid to its attorneys; audits of the billing and invoices of its attorneys to contest the reasonableness of [the homeowners’] attorney's fees.’”

The court ordered the insurer to respond to the discovery requests. The court of appeals denied the insurer’s petition for mandamus relief. While the court of appeals acknowledged that an opposing party’s attorney-billing information may be irrelevant in a given case, the discovery order was, for various reasons described, not an abuse of discretion.

The insurer’s petition for mandamus made it to Austin. The Texas Supreme Court, in a 6-3 opinion, held that the attorney-billing information was not discoverable. The opinion and dissent are lengthy. I set out, verbatim, several of the court’s conclusions below. This is the best way to provide a sense of both the issues discussed and how they were resolved.

Work Product Privilege

The court held that the work product privilege prevented the attorney-billing information from being discovered: “[B]illing records reveal when and where attorneys strategically deploy a client’s resources; which issues were addressed by experienced lawyers as compared to less experienced counsel; the subject-matter expertise of an attorney working on a particular aspect of the case; and who was hired as consultants—including consulting experts and jury consultants—and when. This information provides detailed information regarding a party’s litigation decisions and also illuminates the relative significance of or concern about particular matters. Especially when a party is a repeat litigant, as the insurer is here, decisions revealed through billing records represent strategic choices and are pieces of ‘an overall legal strategy for all the cases in which it is involved,’ which a party must be allowed to develop without intrusion. Discovery of billing records in their entirety would provide a roadmap of how the insurer plans to litigate not only this particular case but also other MDL cases.”

The court rejected the policyholders’ argument that all could be solved through the use of redaction of billing entries: “We also conclude that redacting privileged information—such as the specific topics researched or the descriptions of the subject of phone calls—would be insufficient as a matter of law to mask the attorney's thought processes and strategies. The chronological nature of billing records reveals when, how, and what resources were deployed. With this knowledge, a party in the same proceeding could deduce litigation strategy as to specific or global matters.”

The court made a couple of other important points on the issue of work privilege:

“Our holding does not prevent a more narrowly tailored request for information relevant to an issue in a pending case that does not invade the attorney’s strategic decisions or thought processes. Nor does our holding preclude a party from seeking noncore work product ‘upon a showing that the party seeking discovery has substantial need of the materials in the preparation of the party’s case and that the party is unable without undue hardship to obtain the substantial equivalent of the material by other means.’ But, here, the record bears no evidence of either.”

“We acknowledge that an opposing party may waive its work-product privilege through offensive use—perhaps by relying on its billing records to contest the reasonableness of opposing counsel's attorney fees or to recover its own attorney fees. But in this case, the insurer has stipulated it will not use its own billing records to contest the homeowners' attorney fees. Nor is the insurer seeking to recover its own attorney fees from the homeowners.”

Relevance

The court noted that, “[t]hough the parties disagree about whether the requested factual information is privileged, even unprivileged information is not discoverable unless the information is relevant.”

So the court turned to relevance of the attorney-billing information and held that it was not relevant because “(1) the opposing party may freely choose to spend more or less time or money than would be ‘reasonable’ in comparison to the requesting party; (2) comparisons between the hourly rates and fee expenditures of opposing parties are inapt, as differing motivations of plaintiffs and defendants impact the time and labor spent, hourly rate charged, and skill required; (3) the tasks and roles of counsel on opposite sides of a case vary fundamentally, so even in the same case, the legal services rendered to opposing parties are not fairly characterized as ‘similar’; and (4) a single law firm’s fees and hourly rates do not determine the ‘customary’ range of fees in a given locality for similar services. However, when a party uses its ‘own hours and rates as yardsticks by which to assess the reasonableness of those sought by [the requesting party]’ or seeks to shift responsibility for those expenditures, the party places its own attorney-billing information at issue, making the information discoverable.”

The court also made these interesting observations on the issue: