|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Mark Lanier is wildly successful by several measures. The Houston personal injury attorney’s Lanier Law Firm keeps nearly 50 colleagues busy. The firm’s namesake was on the receiving end of a $9 billion verdict in 2014. Lanier’s eight- and nine-figure verdicts are so numerous that they begin to take on a Monopoly money-quality. Lanier plays himself in Puncture – a movie loosely based on one of his cases. And the entertainment at Lanier’s annual Christmas party – hosting upwards of 9,000 people at his 40 acre home – has included Bon Jovi, Sting, Miley Cyrus, Johnny Cash and on and on.

Clearly much of Mark Lanier’s life involves speaking to judges. But not just the ones who don black robes in courthouses. Lanier also addresses another type of judge, in another kind of house, on a regular basis. It is in one of worship – where he serves as a pastor. I don’t know what else Mark Lanier spends his money on besides spreading holiday cheer, but whatever it is, he’s not doing it on Sundays.

I’m on the phone with Mark Lanier to discuss his career. But my interest isn’t just on this colossal verdict or that. This is Texas – where gushers come out of courthouses as much as oil fields. The state’s motto is Don’t Mess with Texas Plaintiff’s Attorneys. So even if Lanier is one of the biggest fish in the pond, he’s still just a fish. My interest in speaking with Mark Lanier is also about something else. The first line of his website bio reads: “Attorney, Author, Teacher, Pastor and Expert Story Teller.” I’m reasonably certain that none of the 1.3 million other lawyers in America have that combination of hats on their resumes. This is the other Mark Lanier story that I’m after.

I call Lanier’s cell phone at the appointed hour. It’s early in Houston. But in the city known for producing energy, Lanier has a lot himself. We go through the opening pleasantries, and Lanier says I must be desperate for people to interview. I tell the 55 year old Texas Tech Law School grad that I don’t have a lot of questions for him. I figure that a Texas plaintiff’s attorney, who’s also a pastor and expert story teller, will not be providing Bill Belichick-type answers. I’m expecting it to be an easy interview. My plan is to turn on the tape recorder and let Lanier do all the work. I got it right. Lanier was animated, forthcoming, very generous with his time (nearly an hour) and full of great stories, including, not surprisingly, some from the Bible. Despite all his success and fame, Mark Lanier is an aw shucks guy.

By The Numbers

Lanier’s courtroom numbers are jaw dropping. He rang the bell last year for a combined $9 billion verdict (virtually all punitives) against Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. and Eli Lilly, for their diabetes drug Actos causing bladder cancer. Lanier tells me that it came out of a parish in Louisiana not known for large verdicts, in front of a conservative Republican federal judge and following his living out of an RV for three months.

Lanier scored a $253 million verdict against Merck in the nation’s first Vioxx trial. It’s funny. Nine billion makes the Vioxx verdict seems paltry. That verdict ultimately led to a global Vioxx settlement -- with the pharma giant funding close to $5 billion to resolve about 50,000 cases claiming that its painkiller caused heart problems.

Some of Lanier’s other ten-gallon size verdicts include one for $480 million in a contract dispute against Amoco, $118 million in an asbestos trial and $56 million against Caterpillar on behalf of an injured driver of a tractor. Earlier this year Lanier secured a nearly $500 million verdict for five plaintiffs injured by a Johnson & Johnson subsidiary’s metal-on-metal hip implants. While Lanier is obviously known for being a plaintiff’s personal injury lawyer, he tells me that about twenty percent of his work is on the defense side.

I realized that there is something odd about these verdicts. Almost all of the cases are listed on Lanier’s bio on his firm’s website, but with only a description and no mention of the verdict amount. The $8 billion verdict in the Actos case is described simply as “headline grabbing.” That Vioxx verdict? It’s just described as a win. The nearly $500 million hip implant verdict is called “astonishing,” but no mention that it’s half-way to ten figures. Most lawyers with those kinds of verdicts would use more neon than the Vegas Strip to point them out. So maybe Pastor and Expert Story Teller aren’t the only things about Lanier’s bio that are unique.

As you would expect from a lawyer with such huge verdicts, Lanier can hang a lot of plaques on his wall. The number of top lawyer lists on which he has appeared is staggering. These include being selected by The National Law Journal as of the forty most influential lawyers in America for the decade of the 2000s – the only plaintiff’s lawyer on the list. Lanier was named 2015 Trial Lawyer of the Year by the National Trial Lawyers and The Trial Lawyer magazine. He has been profiled by The Wall Street Journal, New York Times and Los Angeles Times, among other papers, as well as made appearances on various cable news shows.

Lanier’s list of accomplishments is staggering for anyone, yet alone a lawyer who looks like he’s still in law school. I ask Lanier about his youthful looks. He jokes that fat cheeks make you look young. He admits that in the early days he regretted it. It created an impression that his cases couldn’t be that big. After all, “if it was a really big case it wouldn’t be in the hands of this kid.” But over time he came to realize that looking on the younger side of his age was helpful. Lanier tells me that he now enjoys not looking as worn out as he feels.

Like many lawyers who have notched a lot of huge wins, Lanier can’t single out one as the most satisfying – but he knows it’s not related to the size of the verdict. In general, he tells me, satisfaction comes from representing “people who truly are desperate for justice, they’re desperate for a solution to a problem, they are desperate for resolution and you’re able to step in and try it for them and to see them afterwards with tears of appreciation and thankfulness.”

Lanier shared with me a fascinating fact about his role in the Vioxx litigation. Of all the thousands of Vioxx cases, Merck wanted to try one of Lanier’s first because he was known then as an asbestos lawyer and not a pharmaceutical lawyer. Indeed, Lanier was not even permitted on the plaintiff’s steering committee for the Vioxx litigation. Likewise, at the time Lanier got into asbestos he was known as a commercial lawyer. He says that nobody wanted to settle his asbestos cases because he wasn’t an asbestos lawyer. Then he got a $118 million asbestos verdict. From then on he was called an asbestos lawyer – until he was called a pharmaceutical lawyer.

The Power Of The Story

I ask Lanier about that unusual description on his bio: expert story teller. What’s up with that? He tells me that his mother was a marvelous story teller. As a kid, when friends came over – pre-video games -- there was more interest in hearing his mom tell stories than playing games or sports. That was where he learned the power of the story. Later, with five kids of his own, Lanier realized that telling stories, and keeping them interesting, is not easy. He read books on the subject and used carpool opportunities for practice.

Lanier is quick to illustrate the power of the story. He points to a PBS series on the Titanic that nobody wanted to watch because the ending was known. Yet, one of the most successful movies of all time is The Titanic. Same boat, same iceberg, same result, Lanier says. The difference: “One told a story and the other was a dry dissertation of facts.” Stories, Lanier said, draw us in.

Not surprisingly, Lanier’s interest in telling stories gets around to the courtroom. After all, as he sees it, what he is doing as a trial lawyer is taking a list of ingredients, called evidence, and putting them together in such a way that it forms one coherent story to tell the jury.

As a lawyer and story teller, does Lanier have a John Grisham novel in him? It seems an obvious question. He’s thought about it he tells me – but not for long -- saying he has too many non-fiction books that he’d rather write. Ironically, while Lanier is not out to be the next Grisham, Grisham’s 2011 novel, The Litigators, is about mass tort litigation against a pharmaceutical company for heart attacks allegedly caused by its cholesterol-lowering drug – named Krayoxx. You know you are an “expert story teller” when the greatest story teller of them all is coming to you for ideas.

Sundays With Mark Lanier

As serious as Mark Lanier is as a lawyer, he is just as serious about another aspect of his life – religion and theology. He has a B.A. in Biblical Languages. Lanier likes to say that he has one foot in the legal world and the other in the world of faith.

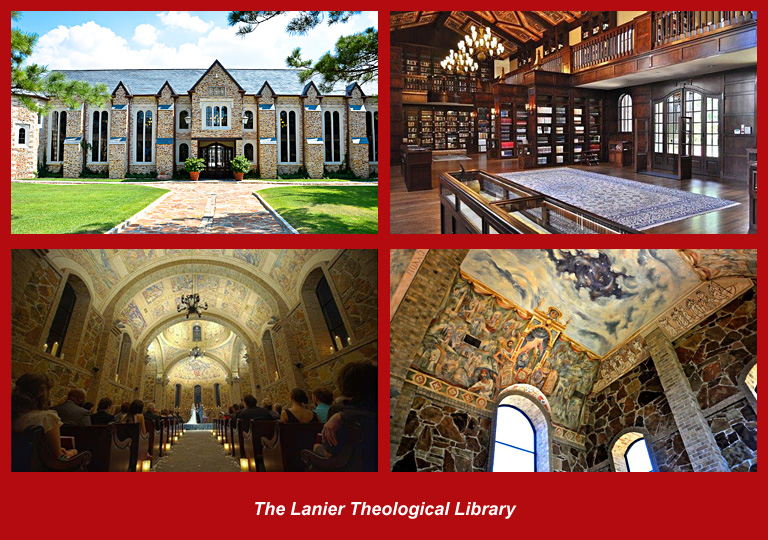

Lanier built The Lanier Theological Library in Houston. Its website describes it as “a growing resource for all students and scholars of the Bible in Northwest Houston. Within the library, you will find a comprehensive collection of books, periodicals, historical documents and artifacts with topics ranging from Church History and Biblical Studies to Egyptology and Linguistics. The LTL regularly hosts events with noted authors, guest lecturers and researchers who will challenge you both academically and spiritually. Come to the Lanier Theological Library and find serious tools for serious study.”

|

|

| |

The library, slated to eventually hold over 100,000 books, is in a building whose interior and exterior looks like something out of Downton Abby. The library also includes The Stone Chapel, a reconstruction of a 500 A.D. church in Tomarza, Cappadocia (Turkey). [Take my word. Check out the library’s website and do a Google image search for it. Trust me.]

But, even with serious religious study as its purpose, it is still necessary to include this on the library’s website: “Please use the leather coasters for your drinks, but do not take the coasters with you. They are not souvenirs.”

Combining religion and the law, Lanier is the founder of the Christian Trial Lawyers Association, an organization whose purposes include advancement of Christian principles as they co-exist with the practice of law. He is also the author of the 2014 book Christianity on Trial – A Lawyer Examines the Christian Faith. This from the back of the book: “[The book] brings a legal eye to examine the plausibility of the Christian faith. Examining the rules that courts follow, [Lanier] probes key issues and interrogates witnesses from throughout history to explore whether it makes sense to accept the Christian worldview or not.”

But Lanier’s religious activities are not all so passive. Come Sundays he steps up to the pulpit as a teacher and sometimes pastor. Lanier teaches The Biblical Literacy class at Champion Forest Baptist Church in Houston to about 750 people. During the week he prepares a ten to fifteen page handout for the class and wakes up on Sunday at 5 a.m. to put together the Power Point. He is currently teaching a series called “Why I’m Not…,” where he lectures on why he is not various things, such as an atheist or an agnostic or various religions other than his own. This is serious stuff. It’s school on Sunday, but this is no Sunday school. Many of Lanier’s lectures appear on the internet. From them it is easy to see why he plays so well in front of juries.

I asked Lanier if there are any contradictions between practicing law and the teachings in the Bible. Not at all. In fact it helps he says, pointing out that the entire legal system in the West is built on the Judeo-Christian codes. As Moses told the Israelites, Lanier points out, if your ox gores your neighbor you have to pay damages. If your ox has gored before then you have to pay treble damages. The legal system, Lanier notes, is based on the Biblical notion of right and wrong. “Justice is a preeminent Biblical concept,” he points out. Looking at what the Bible and practice of law require, Lanier says that both have him walking on the exact same road.

Hunting With Scalia

On three occasions Lanier went hunting with the late Justice Scalia. I ask him if he has any stories about that. Thousands, he says. He tells me a couple. One involves a hunting trip with Lanier, Scalia and a few others sitting around a table for lunch. The topic of Lonesome Dove came up – which did you like better, the movie or the book? Lanier says he liked the book better, not to mention that he was able to read the prequel. Scalia hears the word “prequel” and goes nuts -- claiming that prequel is not a word. And how could a smart guy like Lanier not know that? Lanier insists that prequel is in the dictionary. Scalia counters that maybe it’s in Webster’s third, but that’s not a real dictionary. Lanier says it’s in the Oxford English Dictionary. Scalia disputes that and the two go back and forth. Scalia challenges Lanier to check the OED on his phone. Lanier does so and finds that prequel appears. Scalia mutters what’s happening to this world?

Despite prequel appearing in the OED, Scalia, not to be deterred, begins to lecture Lanier on why it shouldn’t – pointing to Latin derivatives to make his case. But Lanier has a strong comeback – pointing out that he has a degree in Greek and took years of Latin.

But that’s not the end of it. Lanier got back home and sent a letter to the editor of the OED – blind copy to Scalia – now making Scalia’s case that prequel should not appear in the next edition of the dictionary. The OED editor wrote back, saying that while Lanier’s argument was well-reasoned, prequel is a word and it’s staying put. A few weeks later Lanier was in D.C. and had lunch with Scalia in his chambers [Chinese takeout on Supreme Court china, he notes.] Scalia had the blind copy of Lanier’s letter and announced that he was going to send one to the OED himself. But Lanier showed Scalia the OED’s response. And with that the case of In re: Prequel was over, but not before Scalia quipped that the OED editor didn’t have the backbone to remove the word.

Puncture: The Movie

Lanier plays himself in a few scenes in Puncture, a 2011 movie above two young lawyers (one straight-laced and the other drug-addicted), with no means, who file a suit on behalf of an engineer who invented a needle that can prevent accidental sticks to medical professionals. It is a life-saving device. But because of the relationship – and kickbacks -- between hospital purchasing groups and a large needle manufacturer, hospitals had no interest in purchasing it. I watched the movie. It got mixed reviews, but I enjoyed it immensely and recommend it.

The movie is loosely based on one of Lanier’s cases. Really loosely, Lanier stresses to me. In 2004, Lanier settled a case for $150 million, on behalf of Retractable Technologies, against Becton Dickinson & Company, the world's largest manufacturer of medical syringes, for allegedly illegally manipulating the hospital-supply market.

The Next Joe Jamail?

It is hard to think about Mark Lanier without making a comparison to legendary personal injury lawyer Joe Jamail. [Jamail died last year at age 90. He was the richest practicing lawyer in America. Forbes listed his net worth at $1.6 billion.]

Like Lanier, Jamail practiced in Houston. Both lawyers are colorful characters, known for a magical way before juries, have heard the word billion uttered from the jury box and started their careers at Fulbright & Jaworski (Jamail lasted less than an hour there). Of course, there is also a divide between them as wide as that canyon in Arizona. Lanier is the pastor who doesn’t serve alcohol as his Christmas Party. Jamail was gruff, known to sometimes speak in unprintable language and would not have thrown a Christmas party without alcohol – nor even attended one for that matter.

I asked Lanier if he’s the next Joe Jamail. He won’t go anywhere near the comparison. Anyone who thinks they are the next Joe Jamail, Lanier says, needs to take a “big humility pill.” He says that Jamail, along with Ernest Cannon and John O’Quinn and others, “blazed the trail” and all Lanier and others are doing is walking down it. He and others “may take it a little bit further,” Lanier says, “but only because they blazed it so well.”

Lanier also shared a story with me about Jamail. It was hilarious. Of course, not surprisingly for a Joe Jamail story, it’s one that I can’t repeat in a family publication.

The Famous Christmas Party

Lanier is well-known for his annual Christmas party, hosting upwards of 9,000 people at his 40 acre home. The party’s trademark is entertainment from A-list musicians. Over the years partygoers have been treated to, in addition to the aforementioned (Bon Jovi, Sting, Miley Cyrus and Johnny Cash), Faith Hill and Tim McGraw, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Randy Travis, the Dixie Chicks and others. If Santa Claus were real, Lanier would have him there.

In addition to the musical entertainment, the party has included carnival rides, a mini version of the Polar Express working its way around the property and a menagerie that the Houston Chronicle called “only slightly smaller than the Houston Zoos.” It is unquestionably a family event – no alcohol is served – and one with a serious focus on charity. The Chronicle has called it as over the top as it is down to earth.

However, after 20 years, the annual Lanierapalooza came to an end two years ago. Lanier told me that it simply became too disruptive to the house – “We basically couldn’t live here from September until February.” “It was a great thing that ran its course,” Lanier said. “So finally after 20 years my wife and I looked at each other and said we are done.” Would he ever have another? Maybe, he tells me. “If I could get the Rolling Stones, U-2 or Paul McCartney, yeah I might do another one.” |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

“A legislative folly has afforded so plentiful a harvest to us lawyers that we have scarcely a moment to spare from the substantial business of reaping.” The busy lawyer speaking here was Alexander Hamilton. He was describing his good fortune in a letter to Gouverneur Morris in 1784. [1] The war was over and Hamilton was laboring in cases involving New York laws enacted to penalize those who had remained loyal to Great Britain. [2] Little has changed in 230 years. Legislatures are still in the folly business and lawyers of reaping the harvest. Alexander Hamilton was also a founding father of government law work.

Often lost in all the talk about Alexander Hamilton, first Secretary of the Treasury, is that he was also an extremely important New York lawyer. Hamilton was admitted to the bar in 1782 – after just six months of self-study, [3] an exercise that he described in a letter to Lafayette as “studying the art of fleecing my neighbors.” [4] Hamilton had an extensive law practice until his death in 1804. [5] He wrote what is considered to be the first treatise in the field of private law and may have done so while he was studying for the bar. [6] Hamilton certainly did get a lot farther by workin’ a lot harder, bein’ a lot smarter and bein’ a self-starter. [7]

|

|

|

|

| |

Unlike today’s uber-specialization for lawyers, Hamilton handled cases of many stripes, including contracts, creditor’s rights, admiralty, maritime insurance and constitutional law. [8] Yet, despite what Hamilton told Lafayette he was doing to his neighbors, one noted historian wrote that Hamilton “seemed relatively indifferent to money, and many contemporaries expressed amazement at his reasonable fees.” [9] Perhaps Hamilton was motivated by something greater than the paper that would later bare his picture -- an impersonator singing two centuries later: “I practiced the law, I practically perfected it. I’ve seen injustice in the world and I’ve corrected it.” [10]

Ron Chernow, whose award-winning and bestselling 2004 biography, Alexander Hamilton [11], was the inspiration for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash hit musical now on the Great White Way, told me in an e-mail that Hamilton’s life as a lawyer is a “wonderful and overlooked subject” and encouraged me to write about it. I’m not in the habit of turning down writing advice from Pulitzer Prize winners (Washington: A Life (2011)).

Chernow says that Hamilton was “regarded as one of the premier lawyers of the early republic.” [12] And the biographer does an impressive job of making that case – pointing to incredible accolades bestowed on Hamilton by judges who were witnesses to his work. Chernow also describes Hamilton as having a “taste for courtroom theatrics,” “the most durable pair of lungs in the New York bar,” and a “melodious voice coupled with a hypnotic gaze, and he could work himself up into a towering passion that held listeners enthralled.” [13] He also had “an incorrigible weakness for aiding women in need.” [14]

Defender Of The Press And Foreshadowing Donald Trump

One of Hamilton’s most important contributions as a lawyer – and one still felt today by the press – was his representation of Harry Croswell. Croswell was a journalist indicted in New York for libel against President Thomas Jefferson. He was tried in 1803. All that was required to convict was proving that the published statements were defamatory. Truth of the statements was not a consideration. Croswell was found guilty.

Croswell appealed to New York’s highest court -- where he was now represented by Hamilton. In a six hour argument before the bench [Hamilton did not take Burr's advice to talk less], Hamilton maintained that “[t]he right of giving the truth in evidence, in cases of libels, is all important to the liberties of the people.” [15] One of the judges in the case years later stated of Hamilton’s presentation that “a more able and eloquent argument was perhaps never heard in any court.” [16] This judicial admirer adopted, as “perfectly correct,” Hamilton’s argument that “the liberty of the press consists in the right to publish, with impunity, truth, with good motives, and for justifiable ends, whether it respects government, magistracy or individuals.” [17] While Croswell lost – because the court tied -- his case is regarded as the beginning of the adoption of the now fundamental principle that truth is a defense in libel cases. The rule of law that Hamilton advocated was ultimately implemented into New York’s Constitution. [18]

The Croswell case is still cited in judicial decisions two centuries later, sometimes with a nod to Hamilton’s involvement and his significant contribution to a free press. A New York court in 2000 cited Croswell, and Hamilton’s role – calling him a “tireless defender of freedom of the press in New York” -- in its decision to permit a television station to televise a criminal trial. [19]

In a 1972 decision, the venerable District of Columbia Circuit, in a FCC licensing dispute, went out of its way to make the point that Hamilton, owing to Croswell, made the “greatest single contribution” toward preventing the use of prosecution of the press as a political weapon. [20]

Biographer Chernow notes that Jefferson was “not quite the saintly purist that he pretended” when it came to freedom of the press. [21] To that point, Chernow says that Hamilton had Jefferson in mind when, during his Croswell argument, Hamilton stated that “men the most zealous reverers of the people’s rights have, when placed on the highest seat of power, become the most deadly oppressors. It becomes therefore necessary to observe the actual conduct of those who are thus raised up.” [22]

So Hamilton no doubt would not be surprised to learn that one of the candidates for the nation’s “highest seat of power,” after spending a lifetime as a businessman cultivating and playing the press, stated earlier this year: “I’m going to open up our libel laws so when they [the press] write purposely negative and horrible and false articles we can sue them and win lots of money.” [23]

The Manhattan Well Mystery

In Chernow’s biography the author says that Hamilton rarely handled criminal cases, but when he did it was usually on a pro bono basis. This, Chernow says, is evidence that “challenges the historic stereotype of Hamilton as an imperious snob.” [24]

That Hamilton -- whose practice was so heavily dominated by commercial cases -- handled any criminal cases is remarkable, when viewed through the lens of the modern legal profession. An intelligent person today wouldn’t let a commercial lawyer represent them in a jaywalking case. But that was a long time ago and a world away from today’s sharp line that usually separates civil and criminal practitioners.

A criminal case that Hamilton did handle – murder, no less -- was People v. Levi Weeks. One of his co-counsel was Aaron Burr. [“I practiced law, Burr worked next door.” [25]] The Historical Society of the New York Courts credits the Levi Weeks case as the first murder trial in the country for which there is a formal record. [26] The significance of the Weeks case was not lost on Miranda: “Gentlemen of the jury, I’m curious, bear with me. Are you aware that we’re making hist’ry? This is the first murder trial of our brand-new nation. The liberty behind Deliberation.” [27]

The Levi Weeks case reads like an episode of Dateline NBC. It is easy to imagine Keith Morrison, in that creepy – but can’t get enough of – voice describing the facts. On a snowy evening in late 1799, 22 year-old Gulielma Sands left her boarding house. It was the last time that she would be seen alive. She was found eleven days later, fully clothed, in a wooden well owned by the Manhattan Well Company. Her fiancé, Levi Weeks, quickly found himself under suspicion as the murderer. There was also gossip that Weeks had impregnated her. A coroner’s inquest found that she was not pregnant. However, her body was placed on public display so that the curious could decide for themselves. Public interest in the case was huge. Weeks was indicted for the murder of Sands and placed on trial with Hamilton, Burr and Brockholst Livingston at his side. [28] [29]

The defense team claimed that Weeks had an alibi – he was dining with his brother on the night that Sands went missing – and had no motive to kill Sands. The defense also attacked the credibility of a key prosecution witness – Richard Croucher, “a shady salesman of ladies’ garments,” and tenant at Sands’s boarding house – by making him admit that he had quarreled with Weeks. Sands’s promiscuity was also placed into evidence. [30]

According to Hamilton’s son, John, his father was suspicious of Croucher and placed candles on each side of Croucher’s face while he was testifying. After an objection was overruled, Hamilton called upon the jury to “mark every muscle of his face, every motion of his eye. I conjure you to look through that man’s countenance to his conscious.” Croucher, according to John Hamilton’s account, supposedly “plunged from one admission to another.” [31] Following five minutes of deliberation the jury returned a verdict, finding Levi Weeks not guilty. [32]

The manner of proceeding of the Weeks trial is unthinkable by today’s standards. The trial, with seventy-five witnesses supposedly sworn, began on March 31, 1800 at 10 A.M. It proceeded continuously until 1:30 A.M. on the 1st. The trial resumed at 10 A.M. and didn’t stop until the verdict was announced near 3 A.M. on the 2nd. [33]

People v. Levi Weeks, the first murder trial in the country for which there is a formal record, shares several similarities to another murder trial of historic proportions. Levi Weeks had a legal dream team, he allegedly murdered a woman -- with whom he had a marriage connection -- in a gruesome manner, his case had huge public and press fascination and he was found not guilty after just minutes of deliberation. Sound familiar?

Rutgers v. Waddington: Judicial Review

While not as exciting as freedom of the press or murder, Hamilton was involved in a case that has been said to be “a marker on the long road that led to the ultimate formulation of the American doctrine of judicial review.” [34] Rutgers v. Waddington is a highly complicated case that involved the 1783 Trespass Act, “which allowed patriots who had left properties behind enemy lines to sue anyone who had occupied, damaged or destroyed them.” [35] In general, Elizabeth Rutgers, relying on the Trespass Act, sought rent from Joshua Waddington for occupation of her brewery during the war. [36]

A detailed discussion of Rutgers v. Waddington is beyond the scope here. Here is how a federal appeals court summarized it 200 years later in a case involving the impact of treaties on a purchase of land: “On at least one occasion during the Confederation a New York court decided a case in which it was claimed (by no less an advocate than Alexander Hamilton) that a New York statute was invalid because of a conflict with the Articles of Confederation. Rutgers v. Waddington (unreported) (Mayor’s Court of New York City 1784), summarized in 1 J. Goebel, supra, at 132-34. The court was urged to conclude that the state statute, authorizing a trespass action for military occupation of private homes, was contrary to alleged releases effected by the Treaty of Paris, ending the war with Great Britain, and thereby interfered with Congress’s authority under the Articles. The court appeared to accept the proposition that no state could alter the Confederation or a treaty of the United States, but ultimately decided the case by narrowly construing the state statute, in light of the law of nations, to deny any benefit to the claimant. See 1 J. Goebel, supra, 131-37.” [37]

For Hamilton, Rutgers v. Waddington was much more than just a single Trespass Act case involving a rent dispute. Chenow’s biography addresses in detail the impact of the case on Hamilton’s career as a lawyer, the issues surrounding his decision to defend loyalists after the war and his development of concepts that he later expanded upon in The Federalist Papers. [38]

Two centuries after Aaron Burr’s shot heard ‘round the world, Hamilton’s work as a lawyer remains influential. And the former Treasury Secretary is still teaching economics lessons as well. Thanks to the insane ticket prices for the Broadway production of the life of the ten Dollar founding father, my Hamilton-obsessed ten year old now understands supply and demand.

Notes

[1] Francis Paschal, “The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, edited by Julius Goebel, Jr.,” Indiana Law Review, Vol. 40, Iss. 4 (1965), at 599 (“Paschal”), citing 3 The Papers of Alexander Hamilton 512 (Syrett ed. 1962).

[2] Id. at 602.

[3] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, p. 169, Penguin Books, 2004 (paperback) (“Chernow”).

[4] Paschal at 599, citing 3 The Papers of Alexander Hamilton 192.

[5] Hamilton’s two decades as a lawyer are chronicled in The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, a five volume set published by Columbia University Press, between 1964 and 1981, and edited by Julius Goebel, Jr. and others (“The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton”).

[6] Paschal at 600-01, discussing the origin of Hamilton’s practice manual, Practical Proceedings in the Supreme Court of New York.

[7] Lin-Manuel Miranda, “Alexander Hamilton,” Hamilton (Original Broadway Cast Recording), Atlantic Recording Corporation (2015) (“Hamilton Soundtrack”).

[8] See The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, generally.

[9] Chernow at 188.

[10] Hamilton Soundtrack, “Non-Stop.”

[11] See note 3. The details contained in the accounts in Chernow’s book are staggering. The book includes 2,925 endnotes.

[12] Chernow at 189.

[13] Id. at 190.

[14] Id. at 189.

[15] Historical Society of the New York Courts (http://nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/legal-history-eras-02/history-new-york-legal-eras-people-croswell.html).

[16] The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 1, at 848, n.130.

[17] People v. Croswell, 3 Johns. Cas. 337, 393-94 (N.Y. 1804).

[18] The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 1, at 848.

[19] People v. Santiago, 185 Misc. 2d 138, 150 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Monroe Cty. 2000).

[20] Brandywine--Main Line Radio, Inc. v. FCC, 473 F.2d 16, 53 n.167 (D.C. Cir. 1972).

[21] Chernow at 667.

[22] Id. at 669.

[23] Deborah Barfield Berry, “Trump says he’ll ‘open up’ libel laws if he’s elected,” USA Today, February 27, 2016 (www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2016/02/27/trump-says-hell-open-up-libel-laws-if-hes-elected/81042044/).

[24] Chernow at 603.

[25] Hamilton Soundtrack, “Non-Stop.”

[26] Historical Society of the New York Courts (http://nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/legal-history-eras-02/history-new-york-legal-eras-people-weeks.html).

[27] Hamilton Soundtrack, “Non-Stop.”

[28] See Chernow at 603-04 for a fuller description of the death of Gulielma Sands, from which this summary was prepared.

[29] Livingston was himself no my cousin Vinny. He was an officer in the Revolutionary War, a justice of the New York Court of Appeals and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1807 to 1823. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Brockholst_Livingston.

[30] See Chernow at 605 for a fuller description of the trial of Weeks, from which this summary was prepared. Chernow also notes that Sands had “a little weakness for laudanum.” [Laudanum is a type of opium. I had to look that up.]

[31] The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 1, at 700 and noting that John Hamilton’s account of the candle episode is subject to debate.

[32] Id. at 704. Just a few months later Croucher was convicted of raping a 13 year-old girl. Id. at 700, n.33.

[33] Id. at 695.

[34] Id. at 283.

[35] Chernow at 195.

[36] Historical Society of the New York Courts (http://nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/legal-history-eras-02/history-new-york-legal-eras-rutgers-waddington.html).

[37] Oneida Indian Nation v. New York, 860 F.2d 1145, 1151, n.4 (2d Cir. 1988).

[38] Chernow at 194-99.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

The Absolute Dumbest Class Action

Of All Time

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Class actions are a funny thing. Not funny ha-ha. But funny in that they serve such divergent purposes. On one hand, virtually every social movement since the 1950s has been augmented through class actions and they have served to protect constitutional rights. This is the case that Professor Arthur Miller made to Maniloff in the last issue of Coverage Opinions (which, I might add, is a useless publication except for the “Randy Spencer’s Open Mic” column).

On the other hand, Miller also acknowledged the well-known knock on class actions, that there have been some “downright silly” ones. Indeed, just a few days ago, a California federal judge dismissed a putative class action against Starbucks seeking damages from the coffee giant on the basis that its cold drinks contain ice, which lessens the amount of beverage in the cup. And don’t forget the class action against Subway because its “foot long” subs measured fewer than twelve inches. That one settled.

These types of consumer class actions get a lot of media attention because of their silliness and opportunity to portray the legal system as broken – especially when they involve a settlement that gives the class members a pittance and the lawyers gobs of money. These are simply irresistible stories for the media.

Well, when it comes to silly consumer class actions, the shark has officially been jumped. On August 19 a putative class action was filed in the Central District of California, against Envelope Corporation of America, alleging that the envelope behemoth is violating a variety of California consumer protection laws by not stating on its packaging that the glue on its envelopes contains no nutritional value. The plaintiff, for himself and on behalf of all others similarly situated, alleges that ECA is obligated to warn consumers that licking an envelope will not satisfy any of the government’s recommended daily nutritional requirements.

The plaintiff concedes in the complaint that envelopes are exempt from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act information panel requirement because envelopes are not a prepared food. [That’s the little box on the package that tells you the calories and fat content of a food and that three potato chips constitutes a serving]. So the complaint takes a different tack, maintaining that consumers could be led to believe that, because envelope glue enters their mouth when licking it, they are obtaining a nutritional benefit. As a result, the complaint warns that consumers may forego eating other foods, on the mistaken belief that the envelope has already satisfied an aspect of their daily nutritional requirements. Plaintiffs seek medical monitoring to be sure that they have not been physically harmed by inadequate nutrition, on account of NEC’s gross negligence by its omissions, as well as a host of damages for violation of various consumer protection laws, and, of course, the accompanying attorney’s fees allowed by these laws.

The case is Phillip Finley, and all others similarly situated v. Envelope Corporation of America, No. 16-cv-1259 (C.D. Calif. Aug. 19, 2016).

Thank goodness the post office switched to sticker stamps a while back. Can you imagine? |

| |

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

ACT NOW: Big Discount Ending Soon

General Liability Insurance Coverage: Key Issues In Every State

Jeff and I are very pleased to report that the venerable National Underwriter Company is now publishing the 3rd edition of Insurance Key Issues. We are thrilled and honored to be associated with such a long-standing industry leader.

From here out, National Underwriter will handle the pricing. The current 50% discount for the third edition of Key Issues, offered by the earlier publisher, will end on September 16. After that, the price will be higher. If you’ve been considering purchasing a copy of Key Issues 3d, or some extra copies to avoid the hassle of sharing, this is the time to do it. [Please do not read this as a sales pitch. This book does not make Jeff or me rich. We just love seeing it in use.]

See for yourself why so many find it useful to have, at their fingertips, a nearly 800-page book with just one single objective -- Providing the rule of law, clearly and in detail, in every state (and D.C.), on the liability coverage issues that matter most.

www.InsuranceKeyIssues.com

Get the 3rd edition of Insurance Key Issues here www.createspace.com/5242805

and use Discount Code NTP238LF for a 50% discount.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

Nose Bite Litigation – This Is Snot A Joke

|

|

|

|

| |

The DRI insurance message board was recently full of kudos for member Chris Fargnoli on her win in a “nose bite case” before the South Carolina Court of Appeals. Well, when it comes to a nose bite case, we here at Coverage Opinions say sinus up. [Actually, Coverage Opinions is a one man band. There is no us. Writer’s embellishment used to make that work.]

Anyway, there is no way that Coverage Opinions would blow the opportunity to discuss a nose bite case. In fact, in July 2004, CO included an entire article on nose bite coverage litigation. The article looked at a couple of cases where nose biters sought coverage for claims arising out of their actions.

With Chris’s case getting attention, I decided it was now time to take a look at nose bites cases outside the coverage arena. And there are hundreds. Most are criminal. It’s a crime to bite someone’s nose. But there is no shortage of civil ones too. Plus, don’t forget when Uncle Joe grabbed your nose when you were three years old, put his thumb between his two fingers, and declared that he took off your nose. Surely that’s an area ripe for litigation.

With all these nose bite cases, it’s only a matter of time before a CLE company declares nose biting to be the “next asbestos” and offers a two hour program.

First here is a quick look at the recent decision from the South Carolina Court of Appeals in Easterling v. Burger King Corp, No. 5404 (S.C. Ct. App. May 18, 2016). It arises out of a fight in the drive-through of a Burger King (which is strange -- because nose supposedly tastes like chicken).

Gary Eastwood was behind Thomas Easterling in a Burger King drive-through in Charleston. Eastwood rear-ended Easterling twice. The court described what happened next: “Following the second impact, Easterling stepped out of his vehicle to assess the damage. While Easterling was assessing the damage, Eastwood exited his vehicle and approached Easterling in a ‘very aggressive’ fashion. Eastwood lunged at Easterling, put his shoulder in Easterling’s stomach, and grabbed Easterling around the waist. At some point during the altercation, Easterling hit the curb, tripped, and fell backward down the embankment. Easterling stated he must have bumped his head when he hit the ground because he was ‘knocked unconscious.’ When Easterling regained consciousness, Eastwood was on top of him and proceeded to violently bite his nose off.”

Easterling sued Burger King, asserting various theories why BK was liable for his injuries. Easterling lost. The opinion has as many parts to it as a Whopper. Here are a couple of the court’s conclusions: “Easterling failed to produce any evidence that Burger King did not execute economically feasible security measures to prevent a physical assault in its drive-through.” Burger King did not create an unreasonable and dangerous condition by constructing a drive-through lane adjacent to an embankment, which Easterling claims prevented him from exiting the drive-through lane to safety.

I looked at a lot of nose bite cases and the ones in the criminal context were the most interesting. I picked these as my favorites.

Morris v. State, 382 S.W.2d 259 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 1964): The defendant appealed his conviction for maiming. The statute provided as follows: “Whoever shall willfully and maliciously cut off or otherwise deprive a person of the … nose … shall be guilty of maiming.” The physician who examined the victim testified that “the tip of the nose including a part of the cartilage and the part that flares out had been severed.”

The defendant argued that the trial court erred, when it charged the jury that it could convict, based on a finding that the defendant deprived the victim of a “substantial portion” of his nose. Essentially, the defendant’s argument was that, to be guilty, he had to bite off the entire nose. The Texas appeals court disagreed, holding that the inclusion of “substantial portion” in the charge was not reversible error.

State v. Mairs & Mairs, 1 N.J.L. 518 (1795) (yes, nose bite cases go way back): In dicta, the New Jersey Supreme Court stated that, if a person bit off another’s nose, he would be guilty of assault and battery, even if the indictment charged him with cutting off the nose with a knife.

Mathis v. State, 17 S.E.2d 194 (Ga. Ct. App. 1941): While this was an ear biting case, the court drew upon nose biting for guidance. Defendant was convicted of mayhem for biting off someone’s right ear. He argued that, at most, he was guilty of a less serious statute prohibiting “[slitting] or biting the nose, ear or lip of another…” Looking to the more serious statute, which prohibited the cutting or biting off of the nose, the court stated that, if one third of a nose were bitten off, the person would be guilty of that crime, even though the entire nose had not been bitten off. Thus, the statute prohibiting the mere slitting or biting of the nose or ear was not in play for the defendant’s serious ear biting.

In all three cases, the defendants made fine-point distinctions between their particular nose biting and what they felt it should have taken to convict them. While the defendants all thought these deviations were nothing to sneeze at, in each case the court turned up its, well, you know.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

Coming Soon: White And Williams Coverage College Turns 10!

See Why Hundreds Travel From Across The Country For This FREE Event

|

|

|

|

| |

Sharpen your pencils. Get a new Trapper-Keeper. The 10th Annual (Yes, 10th, it’s the big one) White and Williams Coverage College (FREE for most) is quickly approaching – September 22nd at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia. Registration is brisk and we are well on our way to a capacity crowd of students from insurance and related companies from all across the country. Last year there were 600 registered students from 150 companies and 19 states. Coverage College is the social event of the claims season! If you are planning to attend, the time to register is now.

Students can choose from a variety of multi-discipline Masters Classes, exploring a host of coverage issues, taught by experienced White and Williams lawyers.

The College also includes breakfast, lunch, two breaks and a cocktail reception, allowing students to interact and engage with the faculty, fellow students and sponsors throughout the day. You won’t leave hungry. I can promise that. For those in the insurance industry – other than non-sponsor vendors – the Coverage College is free.

Come see why the White and Williams Coverage College draws so many insurance professionals from across the country. Click here http://www.coveragecollege.com for more information.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

Update From The Reporters On The ALI Restatement Of Liability Insurance

(And A Chance For Newcomers To Get On Board)

|

|

|

|

| |

It has now been almost two years since the American Law Institute did a switcheroo and converted its Principles of the Law of Liability Insurance to the Restatement of the Law of Liability Insurance. Just a one word change – but an impact that speaks volumes. So what’s been happening with the project of late? To find out I checked-in with the Restatement’s Reporters – Professor Tom Baker of Penn Law School and Professor Kyle Logue of Michigan Law. The Reporters were kind enough to send me an informative letter for Coverage Opinions readers, which I set out here.

When it comes to the Restatement project, it is a tale of two citizens. I have seen some in the liability coverage world who are very knowledgeable about it – both substance and status -- and others who know very little. For those not familiar with the project, it may seem a daunting task to get up to speed so late in the game. Kind of like tuning in to an episode of Dateline when it’s halfway over. You know someone was killed, and you know the husband is the prime suspect, but you’ve missed the first four twists and turns in the story.

For those in this camp, Tom and Kyle’s update offers one-stop shopping to get familiar with the project, while also being enlightening for those more familiar with the project. I appreciate Tom and Kyle taking the time to put together this thorough update.

Dear Randy,

Thank you for asking for an update about the progress of the Restatement of the Law, Liability Insurance (RLLI). We’re pleased to report that the project is progressing on the schedule we laid out to you in the update last summer.

The RLLI has four chapters. Chapter 1 addresses contract law doctrines with special importance in the insurance context: interpretation, waiver and estoppel, and misrepresentation. Chapter 2 addresses duties relating to the management of potentially insured liabilities: defense, settlement, and cooperation. Chapter 3 addresses general principles of the risks insured: coverage topics such as trigger; the application of exclusions and conditions; and topics related to limits, multiple insurers, and allocation and contribution. Chapter 4 addresses topics related to enforceability and remedies, including bad faith.

The ALI approved the “Tentative Draft” of all of Chapters 1 and 2 and most of Chapter 3 at the May 2016 Annual Meeting. That draft is available in electronic format for a nominal charge on the ALI webpage at this link, where it is called Tentative Draft No. 1 (Restatement 2016). There were a few amendments to this draft at the May meeting, so the final version will be somewhat different, mostly in tiny ways. We ran out of time for discussion at the Annual Meeting just before tackling allocation, so the discussion of the RLLI at the meeting next May will begin with that topic.

In the meantime, we will be finishing up the rest of Chapter 3 and Chapter 4. We will be distributing a draft of these final parts of the RLLI to our Advisers and Members Consultative Group in September and discussing that draft with them in October. The list of the participants in those two groups appears at this link. This is a serious group of insurance practitioners, academics, and judges, so we are getting excellent, well-informed feedback on the drafts.

The plan is to bring these remaining parts to the ALI Council (a truly all star body) for approval in January 2017 and then to the membership for approval at the Annual Meeting in May 2017. In our experience there always are some revisions after the Annual Meeting, so fall 2017 is the earliest that we can expect the truly final RLLI to go to the printer, and it is certainly possible that there will be some issues that will require going back to the Council and the Annual Meeting one more time. If that happens, final approval would not be until May 2018. Restatements are not an overnight project! Readers who would like to see the ALI’s description of how the Restatement process works should look at this link.

Early on we made a decision to focus on topics that apply to all or most kinds of liability insurance, and not to try to address specialized questions that affect only one or two kinds of liability insurance. We’re very pleased with that decision, and not just because it means devoting only seven years to the project instead of twenty. Focusing on general topics means that we have the opportunity to identify the coherent core of liability insurance law and to present it in a manageably-sized volume that explains the most important liability insurance law rules without being too overwhelming. Only history will tell, but we think that the RLLI will be useful to judges, lawyers, and law students, and liability insurance law will be more coherent and predictable as a result. The feedback we’ve received from academic colleagues is that the drafts have already proven useful in teaching and Tom reports that he wished there had been a restatement to consult when he began practicing insurance law in the 1980s.

For people who would like to hear about the project in person, we will be going on the road a bit this year to talk about the project. Tom will be at the DRI insurance coverage event in New York in December and the TTIPS insurance coverage meeting at the Arizona Biltmore in February. Both Kyle and Tom will both be at a San Francisco event the first week in January that will be hosted by Orrick and open to the public. We hope to see many of your readers at these events.

Thank you again for your interest and your efforts to keep insurance practitioners informed about the RLLI. We look forward to seeing you at the Members Consultative Group meeting in October.

Sincerely,

Tom Baker and Kyle Logue

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Randy Evans:

Coverage Lawyer And Political Insider

Randy Evans, partner at Dentons US in Atlanta, is a coverage lawyer. Indeed, he is the co-author (with J. Stephen Berry) of the hefty book Georgia Property and Liability Insurance Law (Thompson Reuters 2014) (I have a copy of it on my shelf) as well as other books on insurance law.

But Evans is also a political insider. And at the highest level. He served as outside counsel to former Speakers of the House Newt Gingrich and Dennis Hastert and later served as a senior advisor to Gingrich’s 2012 presidential campaign. These days, Evans is the Georgia Republican Party’s national committeeman, chair of the Republican National Lawyers Association and co-chair of the Georgia Judicial Nominating Commission. He was also appointed to the Republican National Committee’s Debate Committee, which was responsible for hammering out the details of the Republican presidential debates.

Coverage lawyer and political insider is a seemingly odd combination. Randy was kind enough to answer four questions about his unique dual practice. |

|

|

|

| |

Your credentials in the political arena are lengthy and impressive. Insurance coverage seems out of place on your resume. How did your coverage practice come about?

Both my coverage practice and political involvement developed simultaneously. During college, I met former Speaker Newt Gingrich. During law school, I enjoyed litigation and insurance. So, when I hit the ground after law school, I started both. Increasingly, I noticed how interrelated they were in many respects, especially as my practice became national and then international. Globalization has only made it more so.

Are there any ways that your political experience transfers to your insurance coverage work?

The overlap between politics and insurance coverage is far greater than most folks think. From regulations by insurance commissioners, to statutes by legislatures, to decisions by judges - all of whom are either elected or appointed - the public policy implications of insurance and insurance coverage inevitably overlap. By being involved heavily in both, it gives attorneys, including me, a better view of where things have been, where things are, and where things are going. It also gives coverage attorneys the chance to shape policy as well as predict it, in states where commissioners, legislatures, and judiciaries are in a state of transition.

Politics aside, Donald Trump tapped into the public’s dissatisfaction with Washington and the so-called establishment. Whether he wins or not, do you see other any changes on the horizon in Washington as a recognition of this?

The electorate is in a state of transition. If Trump wins, it could actually translate into the de facto formation of a third political party. There will be the traditional Democrats, Republicans (in control of the Congress) and Trump voters in control of the White House. It is why he describes the Presidential election as not a partisan choice, but instead a choice of more of the same or a new direction for the country. The ramifications of such a transition are enormous and will be manifested in many elections to come as parties realign or disappear and new alliances emerge from the top of the ballot to the bottom.

As a political insider – and especially at the House Speaker level – you surely know things about the process that we on the outside are not aware of. What are some things about the political process that the general public cannot appreciate?

Probably the single most significant unknown thing is the impact of good and reliable data. At the highest levels of government, like the President or Speaker, the information advantage is enormous. As a result, high ranking government officials know what’s coming days, weeks, and even sometimes months before everyone else does. As a result, when you talk to someone high up in the White House or in the Leadership in the Congress, the odds are that whatever you are discussing is dated.

The end effect is what you see now is actually the product of what was done years ago and what we will see years from now is the product of what is being done now. This time lag makes judging any one Congress or President in real time virtually impossible absent major blunders. |

|

| |

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

A Monster: Insurer Sasquashed: #1 Coverage Case Of 2016

|

|

|

|

| |

The Illinois Appellate Court’s decision in Harwell v. Firemen’s Fund Insurance Co., No. 1-15-2036 (Ill. Ct. App. June 30, 2016) is the most significant coverage case of the year to date. And even though the big blotter calendar on my desk says it’s only September -- yes, that’s what I still use – I am confident that nothing in the next four months is going to surpass Harwell.

Yes, I know, I’ve really built this one up. This is hyperbolic even by Coverage Opinions standards. But read on. I’m not overselling the potential significance of this decision from the Land of Lincoln.

The facts of Harwell are simple. I’ll let the court tell them: “In 2006, Kipling [Development Corporation] was building a home in Will County, Illinois. As general contractor, Kipling hired subcontractors to handle specific aspects of the job, including Speed-Drywall and United Floor Covering. When service technician Brian Harwell entered the site to replace a furnace filter, the stairs leading from the first floor to the basement collapsed beneath Harwell, sending him falling into the basement. Harwell sustained injuries and filed suit against Kipling as the general contractor of the building site. He alleged that Kipling was negligent in failing to properly supervise and direct construction and failing to furnish Harwell with a safe workspace and a safe stairway. Harwell also sued Speed-Drywall and United Floor Covering, alleging they had modified or failed to secure the stairwell.”

OK, here’s where it turns from a routine construction site bodily injury case to anything but routine. Kipling was defended in the case by counsel retained by its insurer – Fireman’s Fund. Counsel for Kipling answered an interrogatory from plaintiff Harwell stating that Kipling had a $1 million liability policy with Fireman’s Fund.

However, the Fireman’s Fund policy contained an endorsement providing that, if Kipling did not obtain a certificate of insurance and hold harmless agreement from its subcontractors, then the limit would be reduced to $50,000 (including defense costs) for bodily injury arising out of the acts of a subcontractor. [We’ve all seen endorsements like this – part of the effort by insurers, over the past decade, to limit its exposure for construction site claims.]

After Kipling’s counsel answered the interrogatory, stating that Kipling had a $1 million liability policy with Fireman’s Fund, the insurer sent Kipling a series of letters, stating that the subcontractor endorsement had not been satisfied, and, therefore, the limit of liability under the policy was reduced to $50,000.

The case went to trial against Kipling only. Harwell won. The jury awarded him $255,000 in damages. Kipling went out of business and had no assets to satisfy the judgment. Harwell filed a coverage action against Fireman’s Fund. The insurer maintained that, because the subcontractor endorsement had not been satisfied, the limit of liability under its policy was only $50,000 – and this was exhausted by payment of Kipling’s defense costs. The trial court granted summary judgment for Fireman’s Fund.

The Illinois Court of Appeals reversed – and was none too pleased with what it saw. The appellate court observed that Fireman’s Fund had informed its insured – Kipling – that its policy limit was $50,000. However, Kipling’s lawyers – paid for by Fireman’s Fund, the court was quick to note – informed Harwell that the policy had a $1 million limit of liability. The court saw this as a violation of an Illinois discovery rule, requiring that “[a] party has a duty to seasonably supplement or amend any prior answer or response whenever new or additional information subsequently becomes known to that party.”

The court described the problem this way: “The impact of this violation is obvious: had Harwell known in 2008 that Fireman’s Fund was limiting its liability to only $50,000, he could have sought settlement with Kipling or changed his trial strategy. It does Fireman’s Fund no good to argue that it owed its duty to disclose only to Kipling, its insured; Harwell was the opposing party in the original lawsuit, Fireman’s Fund was controlling Kipling’s defense, and Fireman’s Fund therefore had a duty to be forthcoming under supreme court rules.”

But wait, the court wasn’t done: “Instead of disclosing this information, Fireman's Fund went forward with trial, handling Kipling's defense. At oral argument, Fireman’s Fund’s counsel admitted that no matter what the outcome at trial, Fireman’s Fund would not have paid out on the policy (because of the endorsement limiting liability to $50,000 due to subcontractor involvement in Harwell’s injury). In other words, by not supplementing the interrogatory, Kipling and Fireman’s Fund’s counsel fashioned a ‘heads I win, tails I win’ outcome. But, like so many best-laid plans, this one backfired. In his petition for rehearing, Fireman’s Fund’s counsel alleges that following this Court’s ruling would have forced them to withdraw from representing both Kipling and Fireman’s Fund, and in doing so implicitly acknowledges the conflict of interest inherent in our analysis.”

And, finally, the pronouncement: “Fireman’s Fund’s agenda seems clear: deny coverage to Kipling, control the flow of information to Harwell, fight Harwell tooth and nail through the original case, and after losing the trial—reveal the endorsement. This smacks of sandbagging, which we do not condone. Instead, we find that equity demands that Fireman’s Fund be estopped from asserting the endorsement against Harwell. This adheres to a fundamental maxim of the common law, which applies when dealing with improper discovery disclosures—a party should not be permitted to take advantage of a wrong, which he or she has committed.”

The flaw in the decision is obvious – it seems highly unlikely that Fireman’s Fund and its hired defense counsel for Kipling were in cahoots, as the opinion suggests. The opinion reads like the insurer and defense counsel were acting out a John Grisham novel. I just don’t believe that this was the work of an insurer and its counsel conspiring to create a “heads I win, tails I win” outcome. Instead, this was likely the result of defense counsel doing his or her job -- worrying about the defense of Kipling, and leaving coverage issues, like the applicability and impact of the subcontractor endorsement, to Fireman’s Fund.

But, nonetheless, a look into the crystal ball reveals the problems that this decision can cause. Under this court’s rationale, defense counsel answering interrogatories, regarding the amount of his or her client’s insurance, may be obligated to do more than simply provide the limits of liability. Counsel may also be obligated to disclose reasons why the limits of liability may not, in fact, be what is stated on the policy’s Dec Page. And that’s not always because of something as clear cut – at least in this case, apparently – as the applicability of a subcontractor endorsement.

Rather, in most cases, coverage defenses are spelled out in a reservation of rights letter, which, by definition, leaves open the possibility of a denial, in whole or in part, and possibly for several reasons, until after the litigation has been concluded. There is a lot of “it depends” in a reservation of rights letter. But that wasn’t the case in Harwell, where the applicability of a subcontractor endorsement applied without regard to how the underlying litigation played out. In other words, Harwell was an easier case than most.

Based on Harwell, what is defense counsel’s answer when asked in discovery about its client’s limits of liability? They are X, but… Is sending the plaintiff the defendant’s insurer’s reservation of right letter – which shows the reasons why coverage may not be owed, or not owed in full -- enough to prevent a court from concluding that the insurer did not “sandbag” the plaintiff if it disclaims, or limits, coverage post-verdict? And keep in mind that the reservation of rights letter may have been sent at the inception of the case and, therefore, not be as accurate now based on developments throughout the litigation.

In any event, in general, the Harwell decision seems to introduce coverage issues into the context of underlying litigation. If this decision is seen is followed -- and the Appellate Court of Illinois is not a Montana small claims court -- it could send defense counsel down roads that they surely would not like to travel.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

ABSOLUTE MUST READ: Bad Faith: Turning $30K into $3M (And Easily Preventable)

|

|

|

|

| |

When it comes to bad faith cases, very rarely do they involve claims that an insurer wrongly interpreted a policy provision. Based on the high standard for establishing bad faith, unless an insurer is blatantly ignoring clearly applicable, and binding precedent in making its decision, it would be difficult to prove that the insurer’s conduct rose to the necessary level of culpability.

Rather, bad faith cases almost exclusively involve the manner in which an insurer handled a case. Did it do something that failed to adequately protect its insured’s interests? Did the insurer do something that can be seen as placing its own interests ahead of its insured’s? In addition, for various reasons, bad faith cases have a way of growing out of low limits auto policies. Springsteen made this point in a song called “From small things big things one day come.”

Barickman v. Mercury Cas. Co., No. B260833 (Cal. Ct. App. July 25, 2016) is a bad faith case that never should have happened. It offers a very clear lesson to insurers about how not to turn an easy $30,000 case into a $3,000,000 case, not to mention the declaratory judgment transaction costs. This was policyholder alchemy. And it was easily preventable.

Brickman started out as a straightforward automobile claim. The court described the facts like this: “Timory McDaniel, driving while intoxicated in a car insured by Mercury Casualty Company, ran a red light, struck and seriously injured Laura Beth Barickman and Shannon Mcinteer, who were in a crosswalk with the walk signal in their favor. Barickman and Mcinteer agreed to settle their claims against Timory for her insurance coverage limits, $15,000 each; but Mercury would not agree to additional language inserted by Barickman and Mcinteer’s lawyer in Mercury’s form release of all claims: ‘This does not include court-ordered restitution.’”

The restitution issue came about because Timory was sentenced to three years in prison and ordered to pay $165,000 in restitution. Counsel for the plaintiffs sought the language in the release, that it did not include court-ordered restitution, simply to make clear that his clients were not waiving such right by entering into the settlement. Plaintiffs’ counsel also made clear to Mercury that the insurance payment would be a set-off against the insured’s restitution obligation – as the law allowed. So Mercury was doing anything to harm its insured on that issue.

Mercury spent several months considering whether it would agree to the restitution language in the release. Timory’s criminal defense lawyer instructed Mercury not to accept the added language.

Counsel for the plaintiffs got fed up with the delay in getting the case settled and filed suit against Timory. The case “was settled with a stipulated judgment in favor of Mcinteer against Timory for $2.2 million and in favor of Barickman against Timory for $800,000. Timory assigned her rights against Mercury to Barickman and Mcinteer in exchange for their agreement not to attempt to collect the judgment against her. Mercury paid each woman the $15,000-per-person policy limits.”

Barickman and Mcinteer filed a bad faith action against Mercury. “The complaint alleged Timory’s liability for the catastrophic injuries caused to Barickman and Mcinteer was virtually certain, as was the likelihood that their damages would result in judgments against Mercury's insured well in excess of the $15,000/$30,000 policy limits. As a result, Mercury’s failure to make an offer without unacceptable terms and conditions, its refusal to settle the case at policy limits when it had the opportunity to do so, and its unwillingness to make efforts to reach a reasonable settlement constituted a breach of its obligation of good faith and fair dealing, exposing Timory to excess damages.”

The case went to trial before a retired judge serving as a referee. The referee found in favor of Barickman and Mcinteer and upheld the settlement. Mercury appealed. The appeals court – applying a bad faith test that examined whether the insurer’s conduct was reasonable under all of the circumstances -- affirmed, explaining its decision as follows [lengthy quote to follow but it sums it up in a neat and tidy package]:

“Barickman and Mcinteer each agreed in mid-December 2010 to settle her civil claims against Timory for $15,000, as offered by Mercury, after their lawyer had finished his due diligence regarding Timory’s insurance, assets and employment. The only obstacle to completion of the settlement was the dispute between Algorri [plaintiffs’ counsel] and Mercury over the language of the accompanying release. Mercury contends the addition proposed by Algorri could have been interpreted as a waiver by Timory of her right to an offset and it had an obligation to its insured not to jeopardize that right. . . . However, after hearing conflicting testimony from Algorri and Chang [Mercury representative] regarding their conversations as to the import of the language added by Algorri—‘this does not include court-ordered restitution’—the referee found, in the portion of his statement of decision quoted above, that Algorri assured Mercury both orally and in writing that he intended only to preserve his clients' basic restitution rights and was not seeking to eliminate Timory’s right to an offset for the amounts paid by Mercury. In view of that finding, Algorri’s added language was simply intended to incorporate and make explicit what [2 cited cases] required: A civil settlement does not eliminate a victim’s right to restitution ordered by the criminal court, but the defendant is entitled to an offset for any payments to the victim by the defendant’s insurance carrier for items included within the restitution order. Based on these foundational findings and Timory’s certain exposure to substantial liability, the referee could properly conclude that Mercury’s refusal to accept the release as amended by Algorri or, at least, to present to Barickman and Mcinteer in a timely fashion a revised release that included both Algorri’s language and his explanation of its meaning (for example, by inserting after Algorri's addition, ‘and does not affect the insured's right to offset’) was unreasonable.”

The court also put blame on Mercury for placing the decision whether to settle in the hands of Timory’s criminal defense lawyer, without telling him that plaintiffs’ counsel only sought to preserve his clients’ right to seek criminal restitution and not to disturb Timory’s offset rights.

My take on Barickman is that it seems like a situation of an insurer not being willing to agree to something proposed by the other side, simply because, well, it was proposed by the other side. It seems that it could not have been clearer that the insurer’s concerns were unfounded – based on both the representations by plaintiffs’ counsel and the state of the law. But, no matter, the insurer objected to the requested release language. The lesson is obvious. Choose your battles wisely. Otherwise, from small things big things one day come.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

Consequences For Breach Of The Duty To Defend

|

|

|

|

| |

Admittedly, KM Strategic Management, LLC v. American Casualty Co., 15-1869 (C.D. Cal. July 25, 2016), a case involving an insurer’s consequences for breaching the duty to defend, is likely only impactful to a coverage case involving California law. This is because of California’s unique rules concerning an insurer’s ability to seek reimbursement of defense costs associated with uncovered claims (subject to the ability to establish such apportionment). Nonetheless, it is a very interesting case and worth the minute that it will take to read about it.

KM Strategic Management filed suit against American Casualty Co., alleging that the insurer breached its duty to defend KM in two underlying actions. [There is no discussion in the opinion of the facts of the underlying cases or coverage issues, but such information is not required.] The court granted KM’s motion for summary judgment and held that the insurer if fact did breach its duty to defend.

KM now sought damages. Not surprisingly, it sought all reasonable fees and costs that it incurred to defend the two underlying suits. American Casualty said, aah, but, under California law, it need only pay for the defense costs associated with covered claims. In general, under California law (Buss), when an underlying action involves both potentially covered, and not covered, claims -- a so-called “mixed action” -- an insurer must defend the claim in its entirety. Thereafter, the insurer can seek to recover the costs incurred to defend the claims that were not covered.

For sure such an allocation can be difficult to achieve, as defense work is often performed for the benefit of the entire case -- and not in such a neat and tidy manner that it can be shown that this work was performed for this claim and that work was performed for that claim. But, here, American Casualty had an expert, who reviewed the defense bills and materials from the underlying actions, and concluded that 95% of the defense costs were related to the defense of non-covered claims. So, as American Casualty saw it, if it had to pay all of the reasonable fees and costs that KM incurred to defend the two underlying suits, the insurer was being deprived of its right to limit its obligation to only the defense costs associated with covered claims.

The court was unimpressed with American Casualty’s argument, holding that “having breached its duty to defend, American Casualty is required, as a matter of law, to pay as damages all reasonable and necessary fees and costs that plaintiffs incurred to defend against the underlying . . . Actions, including any fees and costs related to the defense of claims for which there was not even a potential for coverage.”

The court’s decision was not based on its own expressed reasoning, but, rather, arrived at by rejecting American Casualty’s various arguments. But you get a sense that the court was guided by two things. First, even in a so-called “mixed action,” an insurer must defend the claim in its entirety. Second, if American Casualty could breach the duty to defend, and then turn around and limit its defense obligation to only those fees and costs associated with potentially covered claims, it would be getting off without any real consequences for its actions.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 5, Iss. 9

September 7, 2016

This Decision Should Really Trouble Lawyers

|

|

|

|

| |

There is no shortage of decisions that examine whether the acts of a professional qualify as a “professional service,” either for purposes of determining coverage under a professional liability policy or the applicability of a CGL policy’s professional services exclusion. Often-times these cases involve professions that I know nothing about. So I do not have the benefit of any first-hand knowledge whether the acts qualify as a “professional service.” I can follow the court’s analysis, and decide whether I agree, and think about whether the act “feels” like a professional service, but that’s all I can do.

But Sentinel Insurance Company v. Cogan, No. 15C8612 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 15, 2016) is different. It involves the applicability of a professional services exclusion under a general liability policy issued to a law firm. So here I can put myself in the insured’s shoes. And so can many of you.

At issue in Cogan is coverage for defamation counts in a suit filed by one law firm (McNabola Law Group) against another law firm (Cogan & Power). Some lawyers from the Cogan firm had left the McNabola firm and started a competing firm and litigation ensued.