|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

June 26th was the 5th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage.

Mary Bonauto -- the nation’s leading LGBTQ-rights lawyer -- argued the case before the Supreme Court. I had the pleasure of interviewing Mary about the state of LGBTQ law 5 years after the landmark decision.

Mary also shared a lawyer-stress situation that I wonder if anyone can ever top.

The interview appears here in CO as the regular Declarations column. But I originally did it for The ABA Journal website. I hope you’ll check it out:

https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/5-years-after-landmark-gay-marriage-case-mary-bonauto-says-its-gone-swimmingly-well

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Self-Serve Froyo Goes To Court

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Remember when frozen yogurt was not self-serve. You'd go into the froyo store and tell the person behind the counter what flavor you wanted, size and toppings. Then the person went to work putting it together. The whole thing was out of your hands. You had as much control over the quantity of sprinkles you'd get as you did the weather.

Then one day it all changed. Froyo became self-serve. You take a cup – only one size is available and it's what the large used to be – walk up to the machine offering your preferred flavor and gingerly raise the silver lever. The machine snaps to life and you twirl the cup around, slowly filling it with frozen yogurt from the sides to the middle. Then, at some point, the brain cell whose job it is to determine how much frozen yogurt you should eat at one time, sends an instruction to your hand to let go of the lever. All the while you can't believe you're actually doing this yourself. Surely this machine takes special training to operate, you always thought. Then you are off to the toppings bar. And you know what happens there. Six spoonfuls of sprinkles is a lot. But look how tiny they are. How fattening can they be?

Obviously the froyo industry figured out that if you offer it self-serve, and charge by weight, people will eat much more than if they had simply order a pre-determined size. For the froyo business, this was an life-altering as the invention of Penicillin. It's amazing it took as long as it did for them to realize this.

But froyo store owner Blake Lyle wasn't satisfied stopping here. Despite his Froyo What's Up, in Columbia, South Carolina, being self-serve, Lyle offered a second size cup. After all, even with the standard cup being as large as it is, he thought some customers might still want more. So Lyle dubbed the standard cup a size small and added a medium. This was the size of a Kentucky Fried Chicken bucket. If a customer asked for a large cup, the employees were instructed to say that they were all out of them.

Jimmy Gloop was a four-times-a-week customer at Froyo What's Up. Once the store began offering a size medium, Jimmy chose that and filled it up completely. After a month of eating about 15 pounds of froyo, four times a week, Gloop gained 35 pounds and became seriously ill.

Gloop filed suit against Froyo What's Up. In Gloop v. Froyo What's Up, LLC, No. 20-134 (Cir. Ct. S.C., Richland Cty., Mar. 3, 2020), Goop asserted claims for products liability based on failure to warn and deceptive trade practices. As Gloop saw it, there should have been a warning sign that eating too much frozen yogurt can cause weight gain and adverse health conditions. After all, everyone knows that yogurt is a healthy food. So a reasonable consumer would believe that froyo is simply a frozen version of this healthy product. Goop also alleged that, by calling the bucket size a medium, Froyo What's Up was portraying the consumption of 15 pounds of froyo as a reasonable quantity. After all, if a person really wanted to overindulge in froyo, they would buy a large.

Froyo What's Up recently filed a motion to dismiss and is having some problems getting its liability insurer to pick up its defense. I'll stay on top of this.

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue5

July 16, 2020

Encore: Randy Spencer’s Open Mic

Walking, Texting And Falling Into A Fountain At The Mall

Who’s Liable? Is It Covered?

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Most of us walk and text. Of course it’s a dumb thing to do. We all know that. But we do it anyway. And except for very rare instances, nothing bad comes of it. But that’s not always the case. Walking and texting can be very hazardous. So not surprisingly, bad things sometimes happen to people who venture down the street with their eyes looking down instead of ahead. The news is full of stories of people who have suffered mishaps on account of such inattention.

And when people are injured they file suit. Finding someone to blame (other than yourself) is as American as Yankee Doodle. And when people are sued they seek insurance coverage for the mess. This is the story of Christopher Finley v. Albuquerque Retail Properties, LLC, 2nd Judicial District Court, Bernadillo County, New Mexico, No. 15-1256.

The court described the facts in the underlying action as follows. In December 2014, while home from college, Chris Finely was visiting a mall in Albuquerque. Not surprisingly, the twenty-year old college student was sending and reading texts while going in and out of The Gap and A&F. While on his way to the food court he was texting a friend to let him know that he’d see him there in two minutes. But Finley never arrived. With his eyes on his iPhone he walked between two protective benches and straight into a fountain. Since Finley never saw it he had no chance to block his fall and went down very hard.

Fortunately for Finley he suffered no neurological damage. But he was seriously injured nonetheless. His face landed on a sprinkler head and he broke his jaw and sustained significant lacerations, leaving a large scar on his face that could be permanent. Finley also suffered no small amount of emotional injury, especially since the incident was caught on a mall security camera and posted on the internet by a mall employee (now ex-employee).

Despite that Finely seemingly assumed the risk of walking and texting, and was contributorily negligent, he hired a lawyer and filed suit. Finely’s theory was that the risk of shoppers walking into fountains, on account of distraction by texting, was a well-known one for the mall owner, Albuquerque Retail Properties, LLC. Therefore, Albuquerque should have taken steps to protect him.

Albuquerque Retail tendered the Finley complaint to its general liability insurer Pueblo Property & Casualty Co. Pueblo P&C denied a defense on the basis that Finley’s injuries were not caused by an “occurrence,” defined as an accident. Pueblo pointed to the complaint allegations that this was the third incident, in the past two years, involving a distracted texter walking into a fountain at a mall owned by Albuquerque Retail. Plus, it was alleged that Albuquerque Retail knew of other similar mishaps at malls around the country and the risk has even been discussed at retail real estate conventions. As Pueblo saw it, this was not an accident as defined under New Mexico law.

Albuquerque Retail undertook its own defense and the case proceeded to trial. Finley secured a verdict of $485,000 and the jury found him 10% comparatively negligent. The jury accepted the argument that the risk of Finley, distracted by texting and walking into a fountain, was known by Albuquerque Retail. Therefore the mall owner should have done more to prevent it. Finely’s expert argued that the mall should have installed a warning device around the fountain, something similar to the speed bumps on highways that cause vibrations to alert drivers to an upcoming toll booth.

Albuquerque Retail settled the matter for $400,000 (after the court reduced the judgment to $436,500 to account for Finley’s 10% comparative negligence) and filed suit against Pueblo Insurance for the amount of the settlement plus $150,000 for the defense costs incurred.

The court in Albuquerque Retail Properties, LLC v. Pueblo Property & Casualty Co., 2nd Judicial District Court, Bernadillo County, New Mexico, No. 15-8168 held that no coverage was owed to the mall owner. The court accepted Pueblo’s argument that Finely’s injuries were not caused by an accident. The court concluded that Albuquerque Retail had enough reasons to know that, by taking no protective measures, Finley’s fall into the fountain was not an “unexpected, unforeseen, or undesigned happening or consequence from either a known or an unknown cause.” Albuquerque Retail at 7 (quoting King v. Travelers Inc., 505 P.2d 1226 (1973)).

The court stated: “Mall owners are well aware that teens and young adults comprise a large portion of their invitees. Such property owners are also keenly aware that these individuals are likely to be distracted by their phones while on the mall premises.” Therefore, the court held that there was no accident and, hence, no occurrence.

for Pueblo Property & Casualty Co. for Pueblo Property & Casualty Co.

for Albuquerque Retail for Albuquerque Retail

for me for me

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

My Op-Ed In The Wall Street Journal On This Important Legal Bicentennial

Last month was the 200th anniversary of the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors’s decision in Hall v. Hall, the first in the nation to address compensation for a dog bite injury.

I forgot my wedding anniversary last year – really, I did – but I knew that in June 1820 the then highest court in Connecticut issued a decision reversing an award of $175 to a dog bite victim. It’s funny how the brain works sometimes.

I had the pleasure of publishing an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal acknowledging this important legal bicentennial.

North Carolina’s license plates say First in Flight. Connecticut should change its plates: First in Bite.

I hope you’ll check out the op-ed:

https://www.coverageopinions.info/WSJDogsInCourt.pdf

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

A Dog’s Door Dash: When The Delivery Driver Comes Calling

Occupational Hazard For Those Who Bring Those Packages To Your Home

|

|

|

| |

At the height of the great home quarantine of 2020 my front porch doubled as a loading dock. The supermarket, local restaurants, UPS and Amazon sent drivers who pulled up and dropped off their cargo. Even with so-called “no contact delivery,” I know when they have arrived. My enthusiastic canine sentries alerted me.

Despite their ferocious sounds, Barney and Gracie are harmless. But those in the delivery business are not always so lucky. Dog bites have long been an occupational hazard. The injuries can be severe.

Sam Iringan, a driver for a food delivery service, GrubHub, was bitten by a dog while dropping off an order. The customer had given explicit instructions that the driver was to call and honk upon arrival. Mr. Iringan instead entered the property through a closed gate. This made him a trespasser in the eyes of the law. A Colorado federal court in Iringan v. Nickens (2019) dismissed his case.

A judge denied recovery to Zola Mae Heritage, a deliverywoman, who was bitten by a dog while bringing milk to the residence of Ina Mae Gregg. But the Tennessee appeals court in Heritage v. Gregg (1984) ordered a new trial to determine if Ms. Greg knew that her dog had vicious or mischievous propensities. The pooch had previously bitten the mailman.

Genevia Bushnell was bitten by three dogs while delivering health and wellness products to the home of a customer. The Supreme Court of Texas ruled in Bushnell v. Mott (2008) that, even if the owner did not know that her dogs had dangerous propensities, Ms. Bushnell could still have her day in court. The high court determined that the owner could be liable for failing to break-up the attack.

Clarence Rice was knocked over by a dog and seriously injured while delivering gas to a mobile home. A jury found the dog owner’s mother liable and awarded damages. The Supreme Court of Alabama reversed the award, concluding in Humphries v. Rice (1992) that the woman could not be liable as she was neither the keeper nor caregiver of her son’s dog.

Emil Eberling, a 16-year-old newsboy, was bitten by a dog while delivering a paper to a house on his route. A jury awarded him $400. New Jersey’s highest court upheld the award in Eberling v. Mutillod (1917), concluding that young Emil had done nothing to excite the dog, so, therefore, he was not contributorily negligent.

Dog bites are surely an occupational hazard for delivery drivers. Sometimes the wounded driver responds with another delivery – a lawsuit.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

A Rarity: Complaint Alleges Dram Shop Cause Of Action In Dog Bite Case

|

|

|

| |

You certainly don’t see this everyday: A dog bite case with a cause of action for violation of a dram shop statute.

One was filed in March in South Carolina federal court in Lori Zmolek v. Low Tide Brewing, LLC, No. 20-1017 (D.S.C. Mar. 16, 2020).

The complaint alleges that Low Tide Brewing, a bar in Charleston County, encourages customers to bring their dogs and have them mingle with other dogs and customers. In October 2019, Low Tide customer Benjamin Kasper was present in the bar with his Labrador retriever. The complaint alleges that the bartender had served Kasper a significant number of beers, knowing, or that he should have known, that Kasper was intoxicated, not in adequate control of his faculties, and, therefore, presented a danger to others because he was unable to fully control his dog. The complaint alleges that Kasper was ineffectively holding his dog’s leash. Suddenly and without warning, Kasper’s unrestrained dog lunged at plaintiff, Lori Zmolek, clamped its teeth onto the upper part of her right arm and dragged her to the floor.

In addition to claims for strict liability and gross negligence, the complaint asserts a claim under South Carolina’s dram shop statute, alleging that Low Tide was negligent, careless and reckless in “continuing to knowingly sell and serve beer to Kasper after he became intoxicated, and appreciably impaired, causing him to be unable to control or restrain his dog from attacking and biting Ms. Zmolek.”

Let’s see. Dram shop claim – furnishing alcohol to an intoxicated bar patron and they get into their car and cause of accident. All the time. Dram shop claim – furnishing alcohol to an intoxicated bar patron and they get into a fight. Yep. Seen that often. Dram shop claim – furnishing alcohol to an intoxicated bar patron and then they can’t control their dog and it bites another bar patron. Hmm. Can’t say I’ve seen that one before.

Actually, I found one judicial opinion of all fours. And the New York appellate division did not dismiss the dram shop claim!:

In Murphy v. Cominsky, 954 N.Y.S.2d 343 (App. Div. 2012), Plaintiff sought damages for injuries she sustained when her face was bitten by a dog during a party at which alcohol, furnished by defendants, was served to minors. Plaintiff alleged that, as a result of the intoxication of the minors attending the party, they became rowdy, agitating the dog in the home and causing it to bite plaintiff.

The court held: “New York’s Dram Shop Act affords a person injured ‘by reason of the intoxication’ of another person an independent cause of action against the party that unlawfully sold, provided or assisted in procuring alcoholic beverages for such intoxicated person. The statute requires only some reasonable or practical connection between the [furnishing] of alcohol and the resulting injuries; proximate cause, as must be established in a conventional negligence case, is not required.”

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Court Says There’s “A Glimmer of Hope” That Insured Can Recover From In-House Adjuster For Negligence

By Tim Carroll

White and Williams, LLP

|

|

|

| |

There was a lot of hubbub last year about whether a policyholder can sue an adjuster for bad faith. The question arose in the context of the Washington Supreme Court’s decision in Keodalah v. Allstate. The Washington high court’s decision – No, at least not in one scenario. But the court left the door open for a different scenario.

Keodalah involved bad faith. What about negligence? In Phillips v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 104011 (D.S.C. June 15, 2020), the South Carolina federal court held that there is at least a “glimmer of hope” in recovering negligence damages against an insurance company’s in-house adjuster.

As a result, a South Carolina homeowner’s coverage and bad faith suit against a Massachusetts insurance company and a South Carolina adjuster was forced back to state court, due to a lack of diversity of citizenship among the parties. Phillips illustrates the trend of policyholders tacking on claims against an adjuster — typically a citizen of the same state as the policyholder — to prevent suits against out-of-state insurance companies from being removed to federal court on diversity-of-citizenship grounds. The ruling is a setback to insurance companies seeking to keep those suits in federal court after they are removed.

The Phillips plaintiff — a South Carolina homeowner who was burgled — sued her homeowners insurer and the insurer’s in-house adjuster in South Carolina state court for breach of an insurance contract, bad faith, negligence, and other related claims. The insurer was a citizen of Massachusetts; the adjuster, a fellow Palmetto State citizen. The plaintiff alleged, in her state-court complaint, that she captured on camera several individuals burglarizing her home while she was out of state. She alleged she sent the video footage of the burglary to the insurer’s in-house adjuster, but that, later, the insurer fired the adjuster and allegedly misplaced or lost the plaintiff’s file and video. The plaintiff alleged that the insurer should have paid, but failed to pay, for the burglary losses under the homeowner’s policy.

The insurer removed the plaintiff’s state-court suit to federal court, asserting that the court had diversity jurisdiction over the matter, because the homeowner was a citizen of South Carolina and the insurer was a Massachusetts citizen. The insurer argued that the court could disregard the South Carolina citizenship of the adjuster, who was “fraudulently joined” because “there is no possibility of establishing a cause of action against” the adjuster. Thus, the insurer argued, the adjuster was a “sham” defendant “named solely for the purpose of defeating diversity jurisdiction.” The plaintiff filed a motion to remand the suit back to state court. The federal court granted that motion, rejecting the insurer’s fraudulent-joinder arguments.

To defeat a fraudulent-joinder argument, the Phillips court observed, the plaintiff need only demonstrate a “glimmer of hope” in the claim against the in-state defendant. The Phillips court could not say the plaintiff had no chance of success on a negligence claim against the in-house adjuster. In so concluding the Phillips court observed that the Supreme Court of South Carolina has only “declined to recognize a duty of care from an independent adjuster to the insured,” but has not declined to recognize a duty of care from an in-house adjuster, as in Phillips. Observing that, under South Carolina law, “one may sue in negligence the master[,] or the [servant,] or both,” the Phillips court held that, “with the benefit of discovery, there is ‘at least some possibility’ that Plaintiff could establish her negligence claim against [the adjuster] at trial.” The court could not state that the plaintiff had “no chance of establishing the facts necessary to support [her] [negligence] claim [ ].” So, the court granted the plaintiff’s motion to remand the suit back to state court, based on a lack of diversity of citizenship.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Winners Of The Coverage Opinions 2020 Home Quarantine Haiku Contest

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

On May 26th Coverage Opinions announced its latest haiku contest. These are always popular and this one was no exception. There were about 100 entries.

This contest was a little different. Instead of the subject of the haiku being insurance coverage, as is usually the case, it had to be something about home quarantine, working from home, Zoom meetings, and the like. Also, I noted that if anyone wanted to work in an insurance coverage angle, that was fine too.

The entries were fantastic. What a challenge to find the best two. I know every contest judge says that, but I really mean it.

The winners of the Coverage Opinions 2020 Home Quarantine Haiku Contest are as follows. Each will be sent an autographed copy of John Grisham’s just-released novel – Camino Winds.

Coverage lawyer

Blouse no pants on Zoom meeting

Not much coverage

Nina Kallen

Attorney at Law

Boston

Coverage discourse

Zoom meeting that does not end

You’re still on mute Phil

Ellen A. McCarthy, JD

Sr. Product Underwriter and Risk Mgmt. Leader

Vice President

Swiss Re Corporate Solutions

Severna Park, Maryland

Thank you to everyone who entered. If I did not acknowledge your entry please do not hold it against me or think of me a jerk. There were so many entries. It’s hard to reply to everyone. I really do appreciate all of the time that people take to enter.

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Penn Law’s Professor Tom Baker Creates The “Covid Coverage Litigation Tracker”

|

|

|

| |

The number of suits filed by policyholders, in state and federal courts, seeking coverage for business interruption in conjunction with the Covid-19 pandemic, is staggering. It is well into the many hundreds and they address a variety of issues.

Looking for a way to keep track of it all? Penn Law School’s Professor Tom Baker – the Reporter for the wrapped-up ALI Restatement of Liability Insurance -- has created the Covid Coverage Litigation Tracker. As the name says, it keeps track of the litigation, setting out a slew of statistics, including the number of filings on a weekly basis, types of claims being asserted, class action status, law firms bringing the cases, insurance companies named as defendants, the policy forms at issue and so on and so on. The Litigation Tracker also includes a list of all cases filed. There were 670 cases listed when I checked the other day.

But CCLT is not just numbers and statistics. There are also blog posts that are updated on a regular basis that provide analysis and observations. Want to see how Covid-19 coverage litigation compares to some recent major hurricanes, you can find it here.

Tom Baker and a team of Penn Law students use Lex Machina’s legal analytics for insurance litigation platform to identify the federal cases and a host of sources – most significantly Courthouse News Service – to find state court cases.

My favorite blog post from CCLT compares the complaint writing styles of cases involving dentists versus restaurants. This is the kind of drilling down that CCLT does in addition to setting out its menu of facts and figures. Somehow I’m not surprised that it’s the restaurants that quote from Oscar Wilde, while the dentists just spit out the allegations. Speaking of restaurants, CCLT reports that over 40% of the suits in their database involve eating establishments.

Tom and the future lawyers on the project (insurance coverage, no doubt) deserve credit for a job very well done. CCLT is only going to get more useful as courts around the country begin to decide the issues. Bookmark CCLT!

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Gee, That’s Surprising. I Would Have Expected This To Be Insured For More

|

|

|

| |

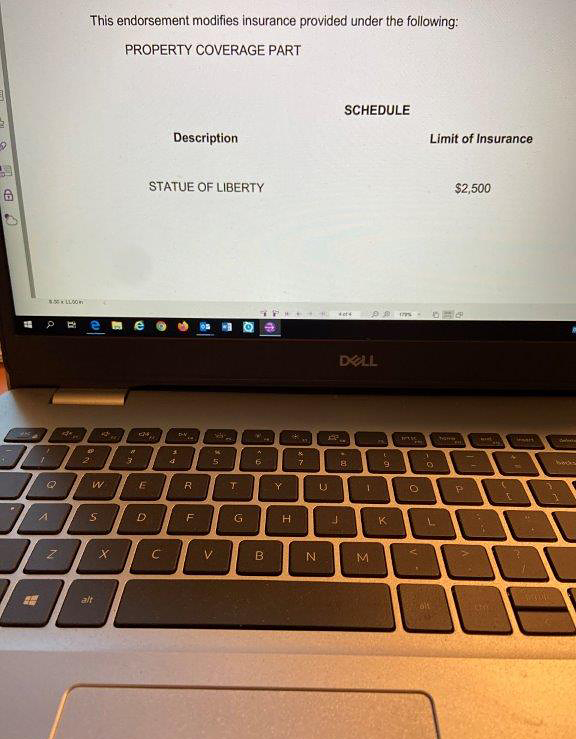

I came across this endorsement in a property policy not long ago. I don’t know the replacement cost for historical landmarks, but I would have expected this one to be insured for more.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

The Most Entertaining Personal Jurisdiction Decision Of All-Time [And It Involves Baseball!]

|

|

|

| |

As someone with a keen interest in quirky legal cases involving sports, I could hardly believe my good fortune when I came across this gem.

The Court of Appeals of Wisconsin’s recent decision in Ewing v. State Auto, No. 2018AP2265 (Ct. App. Wis. June 30, 2020) is the most entertaining personal jurisdiction decision of all-time. [Yes, I recognize the oxymoron in that statement.]

I know -- most entertaining of all-time – that’s a bold statement. Especially since I have read about four personal jurisdiction decisions in my lifetime. The last was in Civil Procedure, Spring Semester 1989. But I’m sure I read about a few while preparing for the bar exam. And that was Summer 1991. So there, I’m not as out of date as you think.

In Ewing, the court addressed whether it had personal jurisdiction over a defendant on account of the manner in which he had been served with a law suit. Specifically, Jonathan Davis, a player for the Lancaster JetHawks, a minor league baseball team, was sued by Skyler Ewing in a motor vehicle action. Davis was (allegedly) served with the complaint by a process server tossing a manila envelope to him, while Davis was walking down the right field line, pre-game, to retrieve his batting gloves from the clubhouse. The toss came from the stands 20 feet above. While doing so, the process server yelled “You have been served.” Davis did not pick up the envelope. A coach did, saw it was addressed to Davis, and gave it to him.

[Folks, let’s pause here for a second. Even as a minor league player, Jonathan “J.D.” Davis was an incredibly elite baseball player. The Lancaster JetHawks are a Class A-Advanced affiliate of the Colorado Rockies. According to Wikipedia, this is often a second or third promotion for a minor league player. That’s all true. What’s also true is that he was not Mike Trout. How hard could it have been for the process server to meet Davis at his car after a game and simply hand him the manila envelope. Postscript – In 2019, Davis, a left fielder/3rd baseman, played in 149 games for the N.Y. Mets, batted .307 and had 22 home runs and 55 RBIs. On August 26, 2019, MLB.com awarded with the MLB Play of the Week for an over-the-shoulder basket catch. Wow!]

Back to the most entertaining personal jurisdiction case of all-time. The trial court dismissed Davis from the suit on the basis that he had not been properly served. Hence, the court did not have personal jurisdiction over him. Ewing was outta-there. [I just complied with my legal obligation to use at least one baseball pun in an article involving baseball and the law.] The Wisconsin appeals court affirmed.

The crux of the appeals court’s decision was the rejection of Ewing’s argument that “personal service is accomplished if the process server and the defendant are within speaking distance of each other, and such action is taken as to convince a reasonable person that personal service is being attempted.”

But the court was not willing to provide an exception to the statutory preference that process should be physically placed in the hands of the party to be served if possible.

While the court noted that exceptions to this preference are permitted, those generally involve situations where the party to be served is being obstinate or taking steps to avoid service. For several reasons, the court concluded that that was not the case with Davis.

My favorite of Ewing’s rejected arguments: “Ewing argues that Davis ‘kept himself in a physically removed area from the process server, thanks to the railings that separated spectators from the baseball field, in order to avoid service.’ The absurdity of this argument is evident on its face. The choice of the location to attempt service was not Davis’s but that of the process server. Davis was a professional baseball player and was merely present at his place of employment, one which is known to separate the general public from the playing field. Rather than attempt to serve Davis at his home or as he entered or exited the ballpark, the process server chose to attend the baseball game and attempt service from the fan section of the stadium. The railing located between Davis and the process server was a function of the server’s choice to attempt service upon Davis from the crowd, not an obstacle to service affirmatively placed by Davis.”

The most entertaining personal jurisdiction case of all-time. If you can top it let me know. I’ll admit you beat me and send you a copy of Insurance Key Issues.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Court Demonstrates The Definition Of An Effective ROR

|

|

|

| |

I have done my “50 Item Reservation of Rights Checklist” seminar/webinar about 20 times, from sea to shining sea, over the past two years. Each time I explain at the outset why ROR letters are so challenging to draft: There is no established format for them.

In other words, there is no formal checklist that an insurer can use and know that, if it crosses off every item, it has foreclosed every possible challenge to the letter from a policyholder. In essence, a policyholder can challenge a ROR for any reason whatsoever. It can do so based on what the letter says or doesn’t say. For this reason, I explain that an “Effective ROR” is any ROR that a court finds is not ineffective. I know that sounds like a silly definition, but that’s exactly what it is. RORs are judged by courts based on what may be wrong with them. To be effective, a court must conclude that not a single thing was.

This definition was demonstrated clearly by the Maryland District Court in Osprey Consulting I v. Westport Insurance Corporation, No. 19-3092 (D. Md. June 10, 2020). The court held that Westport could not withdraw from the defense of an insured, without filing a declaratory judgment action, because it did not reserve the right to do so in its reservation of rights letter.

Westport did reserve the right to “file a declaratory relief action for the determination of its duty to defend and/or indemnify.” This, the court concluded, meant that “Westport only intended to exercise its contractual right to challenge its voluntarily-assumed duty to defend through the institution of a declaratory judgment action.” Therefore, the court concluded that “Westport effectively waived its right to contest its duty to defend, except on those specific, unambiguous terms reserved in the Coverage Letter.” The court observed: “Indeed, if Westport already had the right to change its mind unilaterally and terminate payment of defense costs, it would have no reason to reserve only a right to ‘file a declaratory relief action for the determination of its duty to defend.’”

As I see it, based on the totality of the language in the ROR, as set out by the court, Westport’s letter said enough to have reserved its rights to withdraw its defense without needing to file a coverage action. But the court was not convinced, principally based on Westport’s express reservation of the right to file a declaratory judgment action to determine its duty to defend. So Westport may have been better off not reserving that right. By saying more in the ROR, Westport was given less protection.

The opinion also put the ROR under a microscope in analyzing Westport’s assertion of a “full reservation of rights” to determine if that encompassed the right to withdraw its defense without filing a DJ action. The court concluded that the breadth of the “full” ROR must be interpreted in conjunction with the specific bases on which Westport reserved its rights. Following that review, the court concluded that “full” was not all encompassing.

In the end, the opinion suggests that, even if Westport had reserved the right to withdraw its defense, it would not have mattered. The court seemed inclined to rule that, as a matter of law, Westport could not withdraw its defense without filing a coverage action.

I have read a lot of cases where courts address the effectiveness of an ROR letter. Often times the RORs are lacking and the court’s decision, that the ROR is ineffective, is not surprising. But this is not one of them.

Simply put, Osprey Consulting I demonstrates the difficulty of writing an ROR. With no checklist covering every base, there is no way to know every possible way that the ROR can be challenged as ineffective.

The moral of the story -- An “effective ROR” is any ROR that a court finds is not ineffective.

[Let me know if you’d like me to virtually drop by your office to do my “50 Item Reservation of Rights Checklist” webinar.]

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Court: Mistakenly Cremating A Body – And Giving Ashes To The Wrong Family, Who Buried Them – Is A “Snafu” And Not A Professional Service

|

|

|

| |

This a sad case. But then again, that’s the very nature of liability coverage. After all, nobody makes an insurance claim when things go right.

Ohio Sec. Ins. Co. v. Grace Funeral Home, Inc., No. 6:19-CV-0041 (S.D. Tex. June 28, 2020) involves coverage for two tragic funeral home mistakes. I’ll address one of them here.

After Roberta Salazar’s death in May 2017, her family arranged for an open casket funeral with Ms. Salazar, per her request, wearing a dress given to her by her late husband for their 40th anniversary. However, her body was erroneously cremated and her ashes delivered to another family -- who buried them.

The Salazar family filed suit against Grace Funeral Home, asserting claims that included breach of contract, wrongful cremation, negligence and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

Grace requested that its general liability insurer provide it with a defense. Coverage litigation ensued. The insurer asserted that it had no duty to defend Grace because the suit came within the “professional services” exclusion of the insurance policy.

The Professional Services Exclusion precludes from coverage any injury or damage caused by “the rendering or failure to render any professional service.” It then lists several examples – not an exclusive list -- of “professional services.” Nothing in the list encompasses funerary services.

The court held that the Salazar lawsuit fell outside the scope of the exclusion, emphasizing that the complaint did not mention anything about the quality of Grace’s handling of the body. According to the Court, such claims are the type to which the exclusion would apply.

Here, however, the Court concluded that Grace’s mishap was a “snafu” -- a clerical or administrative error that did not result from professional services. Thus, a defense was owed to the funeral home.

The court did not address what’s a snafu and when does a snafu become a professional service. The best we can take away is that a snafu is a clerical or administrative error or something along those lines. In general, the court knows a snafu when it sees one. I do too. And this was no snafu. This error with Ms. Salazar’s body went to the heart of Grace’s highly specialized business – not botching a burial. A snafu is when the dry clearer gives you someone else’s shirts – not when a funeral home gives you someone else’s ashes.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Court Addresses Argument That State Farm’s “Like A Good Neighbor” Slogan Supports Coverage For Unpaid Claim

|

|

|

| |

The issue in Nelson v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., No. 19-1382 (W.D. Pa. June 3, 2020) is right in the Coverage Opinions wheelhouse.

State Farm advised an insured that a first-party property damage claim was covered. State Farm then changed its mind and refused to pay for water remediation that it had previously authorized. The insured could not afford to complete the repairs.

The insured sued State Farm, asserting the various types of claims that you would expect to see: breach of contract, bad faith, misrepresentation and violation of consumer protection laws. All of this gives rise to some interesting issues – just not ones that I have the mojo to discuss.

But then the court gets to this gem of an issue. The complaint cited to State Farm’s famous “Like a good neighbor” slogan as support for the bad faith and consumer protection law claims.

Needless to say, State Farm was not amused and moved to strike these references as impertinent, stating that the slogan is vague and puffery and “cannot be reasonably relied upon as an express warranty or statement of fact.” State Farm also maintained that its advertising expenditures are irrelevant to whether coverage is owed.

The insured, of course, saw it differently: “Nelson asserts that allegations respecting State Farm’s advertising campaign demonstrate motive to deny claims in bad faith, specifically that State Farm expends so much money in advertising that it is then motivated to deny insurance claims in order to save money.”

The court’s opinion kinda, sorta seems to suggest that the references to the ad slogan isn’t going to be around forever. However, it was too early to nix them at this stage as the bad faith and consumer protection law claims are still in the case: “While the Court acknowledges State Farm’s concern respecting the ultimate scope of this litigation, the Court does not find at this time that the allegations at issue are irrelevant to the degree that this Court should grant State Farm’s requested relief that every reference to State Farm’s advertisement and slogan be stricken from Nelson’s Complaint. On that basis alone, and without addressing the viability of Nelson’s claims which rely on these allegations at this juncture, the Court will deny State Farm’s request to strike averments regarding State Farm’s advertisements and slogan.”

I wonder what would happen if it takes someone 16 minutes to save 15% on their car insurance.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Who Doesn’t Love A Good “Use Of An Auto” Case

|

|

|

| |

I have said this many times. “Use of an auto” is not that hard to understand. It means getting behind the wheel of a car and motoring from point A to point B. So if there is a dispute whether an injury has arisen out of the “use of an auto” [for satisfying the Auto policy insuring agreement or CGL auto exclusion] it must involve something more than someone getting behind the wheel of a car and motoring from point A to point B.

For that reason, cases addressing “use of an auto” have a way of involving bizarre facts. Enter Haskell v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., No. 19-401 (Me. June 11, 2020), where a very intoxicated passenger exited a vehicle before breaking into a home and inflicting harm. This lead to the question whether negligently assisting a drunk friend’s mishaps outside a car is the same thing as negligently causing harm through the car itself?

Grover Bragg drove his intoxicated and delusional friend in his truck, which was insured by State Farm. Bragg’s friend jumped out of the car while it was still moving and then broke into a house owned by plaintiffs Haskell and Witham. After damaging their property, he got back into the bed of the truck before shortly going back into the house and assaulting and injuring Witham.

Bragg’s failure to timely answer the ensuing lawsuit resulted in a default judgment. Bragg and his friend were held liable for $428,000 in damages, affirmed on appeal. The Maine Superior Court also entered summary judgment for State Farm and held that Bragg’s conduct was outside the scope of the vehicle’s insurance policy.

In appealing to the Supreme Court of Maine, Haskell and Witham argued that the incident was an “accident that involves a vehicle” per Bragg’s insurance policy with State Farm, raising the frequently messy “use of an auto” issue -- one that primarily turns upon causation. The Court stated that proximate cause is not necessary, as “coverage will be extended if there is a reasonable causal connection between the use and the injury.”

Using the example from a prior Maine case that a dog bite is not “use of an auto” just because it occurs in a car, the Court emphasized the term “involving.” While not limiting auto accidents merely to car crashes and collisions, the vehicle must in some form link to the injury. The Court was also persuaded by cases from other circuits, which almost unanimously reject the notion that injuries from a physical assault, especially one that occurs outside of the vehicle, have a causal relationship with the use of a vehicle in such situations.

Cases with causation between the vehicle and the injuries usually involve violence being perpetrated from a moving vehicle, such as shooting while in the car. The Court distinguished such cases from those where a car merely transports someone to somewhere where they commit harm. Therefore, Bragg’s friend damaging the property and assaulting Witham did not “involve” Bragg’s vehicle. Regardless of the lower courts’ findings that Bragg was negligent in driving his friend, the Court deemed the damages unrelated to his vehicle and therefore not subject to the coverage of his policy with State Farm. Bragg may have been negligent, but his liability was not the type for which State Farm contracted to insure him.

The Court affirmed the judgment of the Superior Court. In doing so, it made clear that an auto accident is “an unintended and unforeseen injurious consequence involving an automobile,” not something where the perpetrator was transported by automobile.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 5

July 16, 2020

Is Throwing A Beach Ball Down A Hill An Excluded “Game?”

|

|

|

| |

The oooold “games exclusion” was at issue in Atain Specialty Ins. Co. v. Hank’s Dairy Bar, No. 3:19-1085 (D. Conn. July 8, 2020). Resolving an ambiguity in favor of the insured, the Connecticut District Court showed clear hesitance to stretch the exclusion beyond the policy’s express terms.

Steven Devost. Jr. was injured at Hank’s Dairy when he “was picked up by [a] large inflatable ball” and “thrown to the ground.” [I have absolutely no idea what that means or how that happens.]

He brought suit against Hank’s Dairy, claiming that it was negligent to encourage children to push the beach ball down the hill. Hank’s Dairy requested coverage from its commercial general liability policy with Atain. However, the policy included a “Games Exclusion,” which is the central issue of the case. Is throwing a beach ball down a hill considered a “game,” akin to moon bounce jumping or boxing, for which the insurer is not liable?

The Games Exclusion prevents Atain from having a duty to defend or indemnify the insured for incidents arising out of several children’s activities, particularly “moon bounces, moon walks, space walks or other inflatable games or devices;” “boxing games, punching games, or any games that involve kicking;” or “any other game or device that measures or requires the use of any physical force or strength.”

According to Atain, this provision encompasses the use of beach balls, in that they require some degree of force, even if a minimal one, to throw, and are used competitively by children to play games. Hank’s Dairy and Devost, however, argued that the exclusion applies to a much narrower range of complex devices, such as moon bounces and bungee jumping, with much more inherent risk.

Despite technically being an inflated item that can be used in children’s games, the Court rejected the argument that this made the beach ball the type of “inflatable game or device” excluded by the policy, which clearly encompasses larger inflatable items such as moon bounces. Further, the injury did not occur through a “boxing game” as the children were not boxing, punching, or kicking the ball.

As for the more general provision, “any other game or device that measures or requires the use of any physical force or strength,” the Court reasoned that Connecticut contract law requires construing ambiguities in favor of the insured, given that the insurance company drafted the policy. Because “any ambiguity must derive from the language in the contract rather than one party’s subjective perception of the terms,” the Court found little merit in Atain’s claim that “game” entails using a beach ball. Through this interpretation, so too would a basketball and a football fall within the exclusion, a broadening of the terms far beyond inflatable moon bounces. The children were also not participating in any sort of competitive contest that would be central to a “game.” Viewing these many ambiguities in favor of the insured, the Court held that Devost’s claim was outside the scope of the Games Exclusion, therefore implicating Atain’s duty to defend.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Federal Court Stays Covid-19 Coverage Action Pending Upcoming Decision On MDL

There have been several federal court decisions of late that have stayed Covid-19 coverage actions, given the possibility that the case will be transferred to a Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation for purposes of centralized pretrial proceedings. The court’s rationale is why get too involved in the case if it might get transferred. A hearing on whether to create a MDL, for the voluminous federal court Covid-19 coverage litigation, is scheduled for July 30th. Earlier this week the Eastern District of Pennsylvania saw fit to issue a stay, which had been sought by the insured. The insurer argued that “a stay would impugn its right to prompt adjudication of Plaintiff’s claims” and that “transfer to an MDL is not likely in this case, given the great number of insurers, claims, and applicable state laws. The court in Deoleo v. United States Liab. Ins. Co., No. 20-2301 (E.D. Pa. July 14, 2020) disagreed and granted the stay, reasoning: “A short stay may avoid unnecessary briefing on Defendant’s anticipated Motion to Dismiss. A hearing on the JPML transfer and consolidation motions is imminent, so any delay should be slight.”

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|